Should Primates Have the Same Rights as Humans?

In late 2014, a court in Argentina took up the case of Sandra, a 29-year-old who has been held captive all her life. Born in Germany, taken from her parents and transferred to a detention facility in Buenos Aires in 1994, where she has been on permanent public display, Sandra has never tasted freedom. But Sandra’s life will soon change. The Argentine court ruled that Sandra has been illegitimately deprived of her basic rights and should earn sanctuary.

There is one more detail I should note: Sandra is a Sumatran orangutan. She’s an ape. The detention facility she has called home for most of her life is a zoo.

“In a landmark ruling that could pave the way for more lawsuits,” Richard Lough of Reuters writes, “the Association of Officials and Lawyers for Animal Rights (AFADA) argued the ape had sufficient cognitive functions and should not be treated as an object.” The Argentine court agreed, ruling that although she is not biologically human, Sandra is smart enough to be recognized as a “non-human person” with rights that human persons are bound to respect.

Scientists recently discovered that the orangutan, which translates as “man of the forest” in Indonesian and Malay, shares 97% of its DNA with homo sapiens. Being such close cousins, the court in Argentina reasoned, orangutans deserve to be free from bondage. As their native habitat, the rain forest, has receded in recent decades, orangutans have become an endangered species. There are only 7,000 Sumatran orangutans remaining in the world. Sandra could not survive in the wild, given her upbringing, so the court ordered that she be liberated from public display and moved to an animal sanctuary to live out her life in Brazil.

Some 5000 miles north of Buenos Aires, a 40-year-old chimpanzee named Tommy in New York was not quite as lucky in his recent legal battle. One of four chimps the Nonhuman Rights Project (NhRP) has battled to liberate in recent years, Tommy is caged and used for research purposes. Judge P.J. Peters did not dismiss the claim out of hand. Instead, he offered a carefully reasoned rejection of Tommy’s habeas corpus petition:

“While petitioner proffers various justifications for affording chimpanzees, such as Tommy, the liberty rights protected by such writ, the ascription of rights has historically been connected with the imposition of societal obligations and duties. Reciprocity between rights and responsibilities stems from principles of social contract, which inspired the ideals of freedom and democracy at the core of our system of government.”

The rights of personhood, Judge Peters contended, hold only for beings who are capable of fulfilling social duties. “Needless to say,” the court ruled, “unlike human beings, chimpanzees cannot bear any legal duties, submit to societal responsibilities or be held legally accountable for their actions. In our view, it is this incapability to bear any legal responsibilities and societal duties that renders it inappropriate to confer upon chimpanzees the legal rights — such as the fundamental right to liberty protected by the writ of habeas corpus — that have been afforded to human beings.”

One might ask whether this litmus test for deserving human rights would provide grounds for stripping people who are unable to fulfill social duties — comatose patients, people with intellectual disabilities, children — of the rights of personhood. These and other humans, after all, are just as incapable of filing taxes or obeying traffic rules as Tommy (or Sandra). In a footnote, Judge Peters takes on that critique: “To be sure, some humans are less able to bear legal duties or responsibilities than others. These differences do not alter our analysis, as it is undeniable that, collectively, human beings possess the unique ability to bear legal responsibility.”

That’s true, of course. But it is not entirely clear why a human being who is temporarily or permanently unable to take on legal responsibilities deserves full personhood rights while a chimp who is similarly unable to assume these duties is a mere wild animal with no rights at all. Presumably it is the infant’s or the low-IQ adult’s connection with the family of human beings that gives her human rights. But how is such a relationship measured? And what more objective standard is there than DNA? The information encoded in the nuclei of our cells suggests that, deep down, we are remarkably similar to the higher primates.

These cases probing the boundaries of the human community bring to mind a passage from Book 8 of Plato’s Republic. The hallmark of the democratic city, Socrates said, is liberty. But liberty quickly degenerates into license, he warned, and in the end the people “finally pay no heed even to the laws written or unwritten” and “may have no master anywhere over them.” The anarchy that ensues is the “fine and vigorous root from which tyranny grows.”

The descent to tyranny is swift and colorful. Plato describes the flood of liberty breaking down every distinction that makes society possible: slaves claim they are as free as their masters, children lose all respect for their parents, students stop listening to their teachers, and—perish the thought—women claim equality alongside men. But the democratic city is at its absolute breaking point when even the animals get into the act:

“Without experience of it no one would believe how much freer the very beasts subject to men are in such a city than elsewhere. The dogs literally verify the adage and ‘like their mistresses become.’ And likewise the horses and asses are wont to hold on their way with the utmost freedom and dignity, bumping into everyone who meets them and who does not step aside. And so all things everywhere are just bursting with the spirit of liberty.”

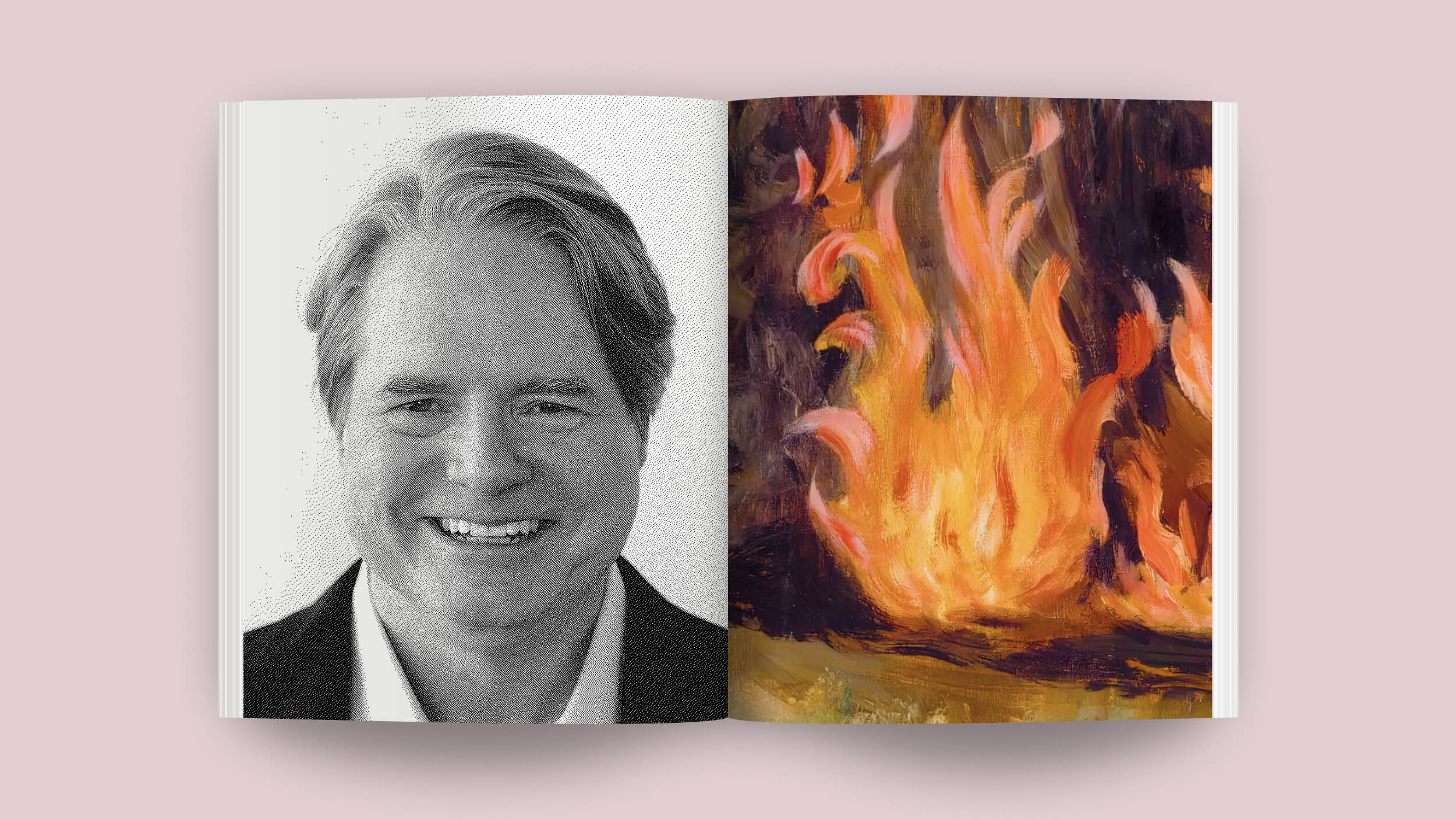

If uppity animals blithely knocking into humans while walking down the street is truly a sign of impending doom, democracy may be close to its demise, especially in Argentina. But Plato may be wrong that widening the scope of liberty to non-human animals portends the loss of civilization. I mean, just look at Sandra’s face:

Image credit: Shutterstock.com