What is the Green New Deal?

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez stops by the Sunrise Movement's sit-in protest at Congresswoman Nancy Pelosi's office. Credit: Sunrise Movement / Twitter

- Recent protests by the Sunrise Movement have taken the Green New Deal from forgotten policy to trending hashtag.

- The Green New Deal aims to move the U.S. to 100% renewable energy within a decade.

- Proponents also hope to catalyze a top-down restructuring of the U.S. economy and advance social justice issues.

In October of last year, the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change released a special report, titled ‘Global Warming of 1.5°C‘. The report’s authors believed that humanity could still limit global warming to 1.5° above pre-industrial levels, if we could curb carbon emissions by 49 percent of 2017 levels by 2030 and then achieve carbon neutrality by 2050.

Is such a goal achievable? Theoretically, yes, but it would require a massive undertaking by governments and the private sector the world over.

A month later, the Sunrise Movement, an advocacy group of young people tackling the issue of climate change, staged a sit-in protest at Congresswoman Nancy Pelosi’s office. Freshman Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez also made an appearance to show her support for the protestors.

Both Ocasio-Cortez and the Sunrise Movement advocate for what is called the Green New Deal, a phrase that has since caught the public’s attention. What is this Green New Deal, and can it provide the United States an answer to the impending dangers of climate change?

A man holds a placard reading ‘Go Solar’ during a rally calling for action on climate change on November 29, 2015, in Rome a day before the launch of the COP21 conference in Paris.

(Photo: Tiziana Fabi/AFP/Getty Images)

A short history of the Green New Deal

Like its namesake, President Fredrick D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, there’s nothing truly new about the Green New Deal. The concept has been floating around at least 2007, when Thomas L. Friedman used it in an op-ed for TheNew York Times. He later expanded the idea into a book, Hot, Flat, and Crowded, which was read by President Barack Obama.

Obama would include aspects of a Friedman’s thesis in the 2009 stimulus package. Of the $800 billion spent as part of the Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, $90 billion was set aside for green initiatives such clean electricity, renewable fuels, smart grids—a move Politico called “a prototype Green New Deal.”

Around the same time, commentator Van Jones used the phrase to describe a push for a green economy that could simultaneously increase jobs and teach labor skills, and British economist Richard Murphy founded the Green New Deal Group. The United Nations called for a global green deal in 2009.

The idea lost immediacy as other political battles pushed to the forefront of the cultural wars, but it would reemerge as part of Bernie Sanders and Jill Stein’s 2016 campaigns.

After the Sunrise Movement’s sit-in protest, Ocasio-Cortez created a draft for a proposal for a Select Committee for a Green New Deal, which 40 lawmakers acceded to support. Since then other lawmakers, politicians, and climate hawks have also championed the deal.

The new(ish) green deal

The Green New Deal has never been a unified movement. As its history shows, it’s a set of general goals promoted by a loose-knit association of progressives and advocacy groups. What follows is an overview of the Green New Deal as synthesized from Ocasio-Cortez’s select committee proposal, the Green Party’s proposal, and the Sunrise Movement’s list of goals.

The Green New Deal’s primary goal is to transition the United States’ economy to 100 percent renewable energy within 10-12 years.

To meet this goal, greenhouse gases would need to be eliminated from industry, agriculture, manufacturing, and transportation; current electric grids would also need to be replaced with smart grids; and residential and commercial buildings would need to be retrofitted for sustainable energy efficiency. Among other changes.

This target alone is a staggering enterprise, as renewable energy accounts for only 18 percent of the total power generated in the U.S. (Though, this figure represents double the contribution from 2008 and costs for such technologies continue to go down.)

“It’s going to require a lot of rapid change that we don’t even conceive as possible right now,” Ocasio-Cortez told 60 Minutes. “What is the problem with trying to push our technological capacities to the furthest extent possible?”

Green New Deal proponents see the government, not private industry, as the driving force for this rapid reindustrialization. In her committee proposal, Ocasio-Cortez argued the necessary scale of such an investment is too large for the private sector and incentivizing companies won’t produce necessary results within the mandatory timeframe.

Through a massive economic investment, the government would offer green businesses low-interest loans, prioritize green research for grants, and promote green technology as a major U.S. export. In the words of the Green Party, the U.S. government would remodel our “gray, old economy” into one that is “environmentally sound, economically viable and socially responsible.”

Michigan artist Alfred Castagne sketches WPA construction workers. The WPA was one of the largest New Deal agencies, employing millions of workers.

(Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

More New Deal than green deal?

But the Green New Deal borrows more from FDR’s legacy than a pithy name. Its supporters aim to use it as a catalyst to radically restructure of the U.S. economy and its social structure. They envision to eliminate poverty, reduce income inequality, and advance social justice.

“Obama grafted his green agenda onto a response to an economic emergency, while Ocasio-Cortez and other left-of-Obama activists are arguably trying to graft their economic agenda, including a government job guarantee and even universal health care, onto a response to a climate emergency,” wrote Michael Grunwald at Politico.

Converting the U.S. economy to renewable technology would create millions of jobs and an imperative need to educate the workforce. To meet this commitment, the Green New Deal would guarantee citizens the right to a job and education, enshrining alongside this guarantee the right to a living wage, safe workplace, and fair trade in deal.

Proponents hope the national funding needed to meet such a commitment will funnel into historically disenfranchised communities and begin breaking down deeply entrenched social barriers.

The Green New Deal also calls for a rebalancing of democratic norms, and its various forms have proposed a multiplex of ideas. These include:

- Universal health care

- Universal basic income

- A right to affordable housing

- Restoration of Glass-Steagall

- Revoking corporate personhood

- Abolishing the Electoral College

- Repealing the Patriot Act

- Reestablishment of strong labor unions

- Breaking up of “too big to fail” banks and end of bailouts

- Relieving debt for students and homeowners

- Reducing U.S. military funding and overhauling the military-industrial complex

No doubt one of the appeals to the Green New Deal is its sweeping approach. If your political alignment is left, center, or even right-of-center, chances there’s an aspect of the deal you can get behind.

An environmental activist wearing a face-mask depicting US President Donald Trump takes part in a demonstration in front of the United Nations building.

(Photo: Lillian Suwanrumpha/AFP/Getty Images)

A path forward?

Despite being galvanized by popular support, Green New Deal has many political headwinds to overcome.

Messaging. As David Roberts notes at Vox, the Green New Deal currently enjoys popularity. He points to a Yale Program on Climate Change Communication survey, which shows a majority support among American voters, even moderate Republicans. But Roberts is quick to point out that the poll’s wording promotes a proponent’s worldview and does not contain negative language like “taxes,” “increased costs,” and “spending.”

“In the real world, if the GND looks like it has any chance of becoming a reality, it will face a giant right-wing smear campaign,” he writes. “And keep in mind, the right-wing machine does not have to win that messaging battle. It just has to fight it, furiously, enough to make the GND controversial, to polarize the issue and freeze it in the same paralysis that grips the rest of US politics.”

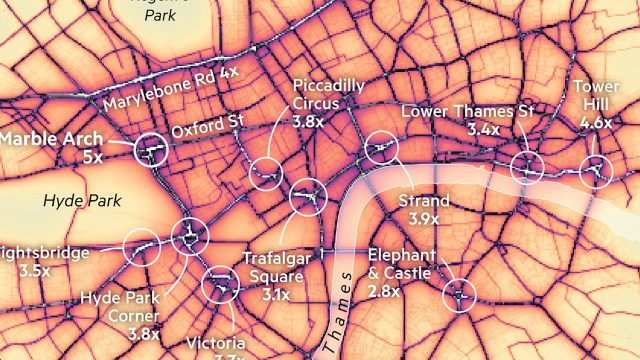

Unequal representation. A historical study by Martin Gilens and Benjamin Page looked at 40 years of U.S. government decisions. They found that the more elite and special interest groups favored a political change, the more likely that proposal would be passed. For the average voter, the correlation was a flat line.

In his TED talk, Harvard professor Larry Lessig cites Gilens and Page to show the necessity for us break down government by special interest and provide equal voting power for all citizens. And few special interests are as entrenched as the fossil fuel industry.

“We will get nothing from this government till we get this,” Lessig said. “You want this government to address the problem of climate change, we will not get climate change legislation until we address this fundamental inequality in this broken democracy.”

While the Green New Deal seeks to fix such democratic concerns (e.g., ending the Electoral College and congressional lobbying), it may be an attempt to build the cart while riding the horse to market.

Scope. The deal’s biggest hurdle may be its most attractive quality: its extensiveness. As high concept becomes political reality, aspects of the deal will need to be revised, reworked, and dropped altogether. This process will create division lines among proponents, fracturing much-needed support.

“Occupy Wall Street movement fizzled out in large part because of its ridiculously fissiparous list of demands and its failure to generate a leadership that could cull that list into anything actionable,” writes Atlantic senior editor David Frum. “Successful movements are built upon concrete single demands that can readily be translated into practical action: ‘Votes for women.’ ‘End the draft.’ ‘Overturn Roe v. Wade.’ ‘Tougher punishments for drunk driving.'”

To avoid Occupy’s fate, the Green New Deal will need to whittle itself down to something approachable to a majority of lawmakers and palatable to their constituency, a move that may prove unappealing to firebrands like Ocasio-Cortez. If it can’t, Green New Deal proponents may need to cede to less comprehensive bills, like the recently introduced Energy Innovation and Carbon Dividend Act, which has already garnered some bipartisan support.

Trump. Of course, all of this ignores the elephant in the White House. President Donald Trump’s skepticism over climate change, his removal of the U.S. from the Paris Agreement, and his buddy-buddy relations with the fossil fuel industry all but guarantees Green New Deal policy will be a nonstarter for the next two years.

Add to that the Republican control of the Senate with moderate Democrats’ worries over reelection in contested districts, and Green New Deal has no realistic path forward. For the moment, it is high-level framework with which to build 2020 platforms. And the longer we argue over solutions, the less time we have to implement them.