Three New Lessons for Columbus Day

In the run-up to Columbus Day, an infographic sailing around the web is busting myths about Christopher Columbus and condemning him as a “sex slaver, mass murderer and champion of sociopathic imperialism.” The information in Matthew Inman’s screed isn’t new—he draws it from 20th-century books by Howard Zinn and James Loewen—but his packaging surely is. Judging by the hundreds of thousands of people who have “liked” his essay and the thousands of tweets, hating on the namesake of today’s holiday has mass appeal. Here’s a taste:

I – Columbus was no hero to Native Americans or his fellow sailors

I am not about to rain on this anti-Columbus parade. The Italian leader of four Spanish voyages to the New World was no saint, to say the least. In the initial assessment of the Native Americans recorded in his journal, Columbus wrote he “could conquer the whole of them with fifty men, and govern them as I pleased.” Native Americans, he thought, “would be good servants and I am of the opinion that they would very readily become Christians.” Columbus was an opportunist and something of a bastard even to fellow Europeans. Though he admits in his journal entry of October 11, 1492 that “the land was first seen by a sailor called Rodrigo de Triana,” he cheated his fellow sailor and fudged the record to claim the lifetime pension King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella promised to the first man who saw land.

But there is nuance to be added to the Columbus backlash, and some original polling data (a Praxis first!) reveals what Americans of various stripes think about the man who is sometimes said to have discovered America.

2 – Most Americans have encountered criticisms of Columbus, but a majority still consider him a hero

In a survey I commissioned for Big Think in September through the polling agency Toluna, 55 percent of the 300 respondents say they had, at some point in their education, “read or discussed ideas that are critical of Christopher Columbus.” Not surprisingly, the younger the subjects are, the more likely they are to have heard these critiques: 70 percent of respondents aged 18-34 have encountered critical takes on Columbus in school, compared to 52 percent of respondents aged 35-54 and only 44 percent of those over 55.

Over 75 percent of the respondents agree with the statement that “history teachers should provide information about the negative aspects of what happened to Native Americans after Columbus’s journey to America,” compared to 14 percent who disagree.

But when asked which statement better characterizes Columbus, more respondents chose the sunny side of the 15th-century Italian explorer: “brave sailor who discovered America” was the choice of 54 percent of respondents, while 36 percent selected this statement: “the person whose voyage to America set the stage for genocide and disease for Native Americans.” So many Americans seem to hold on to a romanticized portrait of the sailor even when they are exposed to his dark side.

3 – Blacks and Hispanics are more likely than whites to harbor a critical attitude toward Columbus

Many more Spanish speakers in the United States seem to be critical of the Spanish expeditions to the Americas in the 15th century than are non-Hispanics. Only 40 percent of Hispanic or Latino respondents chose the “brave sailor” option as the best description of Columbus, while 48 percent preferred the “genocide and disease” statement. Among African Americans, the numbers are more lopsided: only 30 percent chose “brave sailor” while 63 percent agreed more with “the person who…set the stage for genocide and disease for Native Americans.”

Compare these numbers to the views of the white subjects, where the numbers are basically inverted. Whites preferred the “brave sailor who discovered America” line to the critical description by a margin of 58 percent to 30 percent.

Why are racial and ethnic minorities less sanguine than whites about Columbus’s legacy? It could be due to a general feeling among underprivileged communities that America was built on the backs and through the oppression of people like them. The mental health problems of Aaron Alexis, the Washington, D.C., navy yard shooter, may have been exacerbated by a perception of racial discrimination, and countless studies point to the continued relevance of race in minorities’ housing, education and employment opportunities. It stands to reason that today’s disadvantaged Americans might be more sensitive to the oppression of Native Americans half a millennium ago.

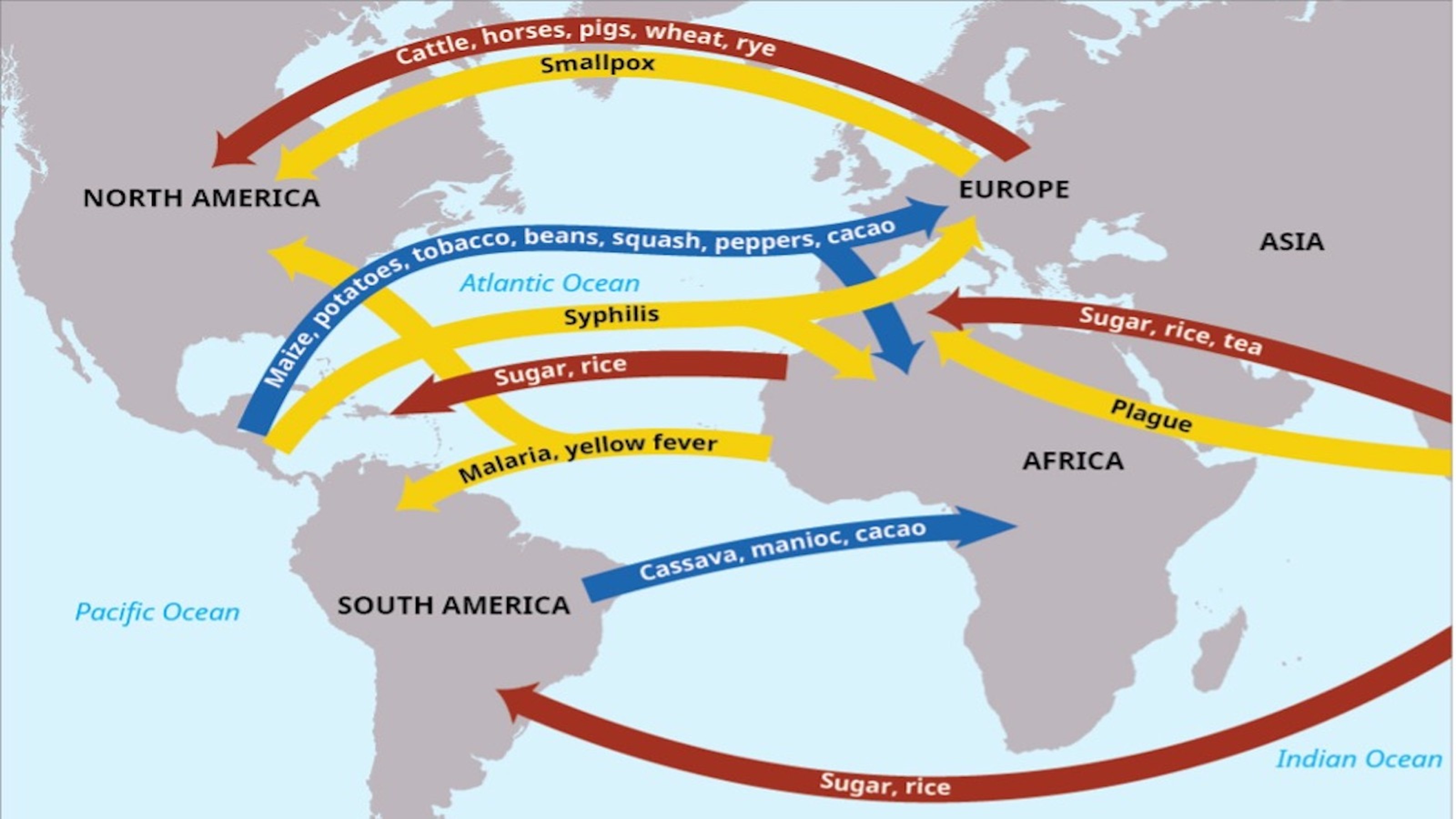

A thought on Inman’s proposal to replace Columbus Day with “Bartolomé Day”

The unrestrained anger against Columbus found in Matthew Inman’s popular infographic goes overboard at times, such as when he blames the explorer for single-handedly launching the Atlantic slave trade or for causing the deaths of millions of Native Americans. The 3-5 million Indians who died of starvation, violence and disease in the first few decades after contact do not all fall on Columbus’s head. Most of this carnage was inadvertent—the antibody-poor Native Americans, as Alfred Crosby details, succumbed to microbes Europeans toted to the New World, particularly the smallpox virus. And there were conquistadors with far more blood on their hands than Columbus. Hernan Cortes, the butcher of the Aztec empire, is only one example.

Finally, it is a bit simplistic of Mr. Inman to present Bartolomé de las Casas as a more deserving honoree for an American holiday. Though las Casas did bravely report on the worst Spanish crimes against Native Americans and defended the Indians in a famous debate in 1550, his argument on behalf of the Native Americans granted two at-best partial truths about their culture—idolatry and human sacrifice—and advanced a specious justification of their practices. The Indians were only committing a “probable error,” las Casas claimed: a moral failing inexcusable in the eyes of God but understandable and excusable in the eyes of human beings. By sacrificing humans, las Casas untenably argued, the Indians were just trying to give a gift of ultimate value to their gods; and anyway, their priests said it was OK, so how would they have known any differently?

Aside from his unsuccessful logical jiu jitsu to defend Native American practices, Las Casas held Indians as slaves and, after freeing them, advocated the importation of Africans. He watched Spanish monks as they burned the “the vast majority” of “hieroglyphic books in the Maya world” to facilitate the Mayans’ conversion to Catholicism. (He may have regretted this crime, but did little to stop it.) His story belies Mr. Inman’s facile claim that while the evil Columbus raped young girls and stole gold, the saint las Casas “found his humanity.” The fact is that many criminal acts conspired to launch America as we know it. Machiavelli said that all great foundings are built on great crimes, and he was, lamentably, correct. It will always be a complicated endeavor celebrating America’s founding moments.

Image courtesy of Shutterstock