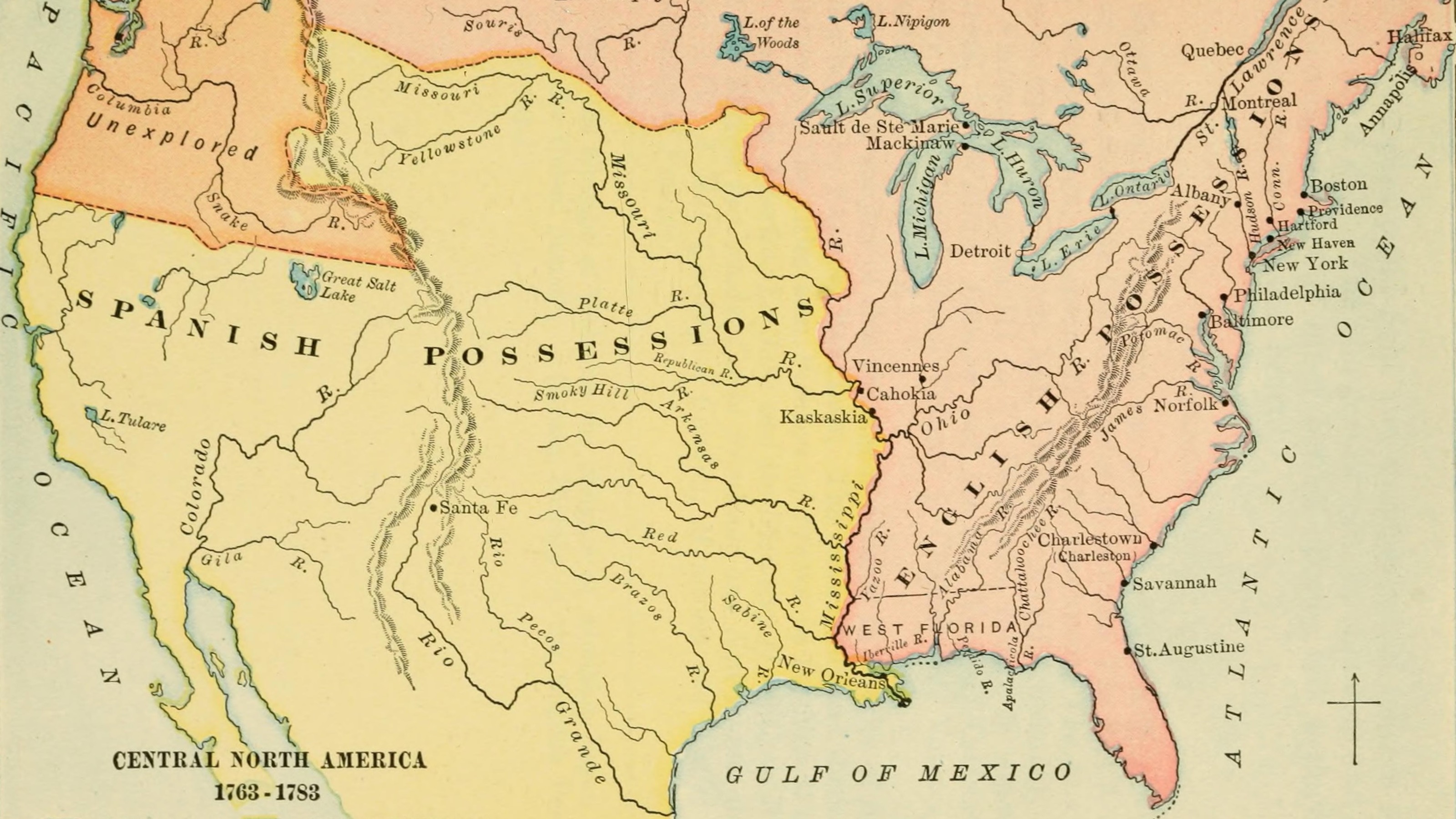

Why the map-busting American Revolution was also the “first” First World War

Credit: McLaughlin, Andrew Cunningham / No restrictions / Wikimedia Commons

- The American Revolution — sparked by skirmishes in Massachusetts — was one theater in a global conflict.

- The Second Hundred Years’ War (1689-1815), primarily fought between France and England, was actually a series of eight wars: Americans fought in every one of those wars.

- The Declaration of Independence, on July 4, 1776, was effectively an invitation to France and Spain to join the Americans in battle.

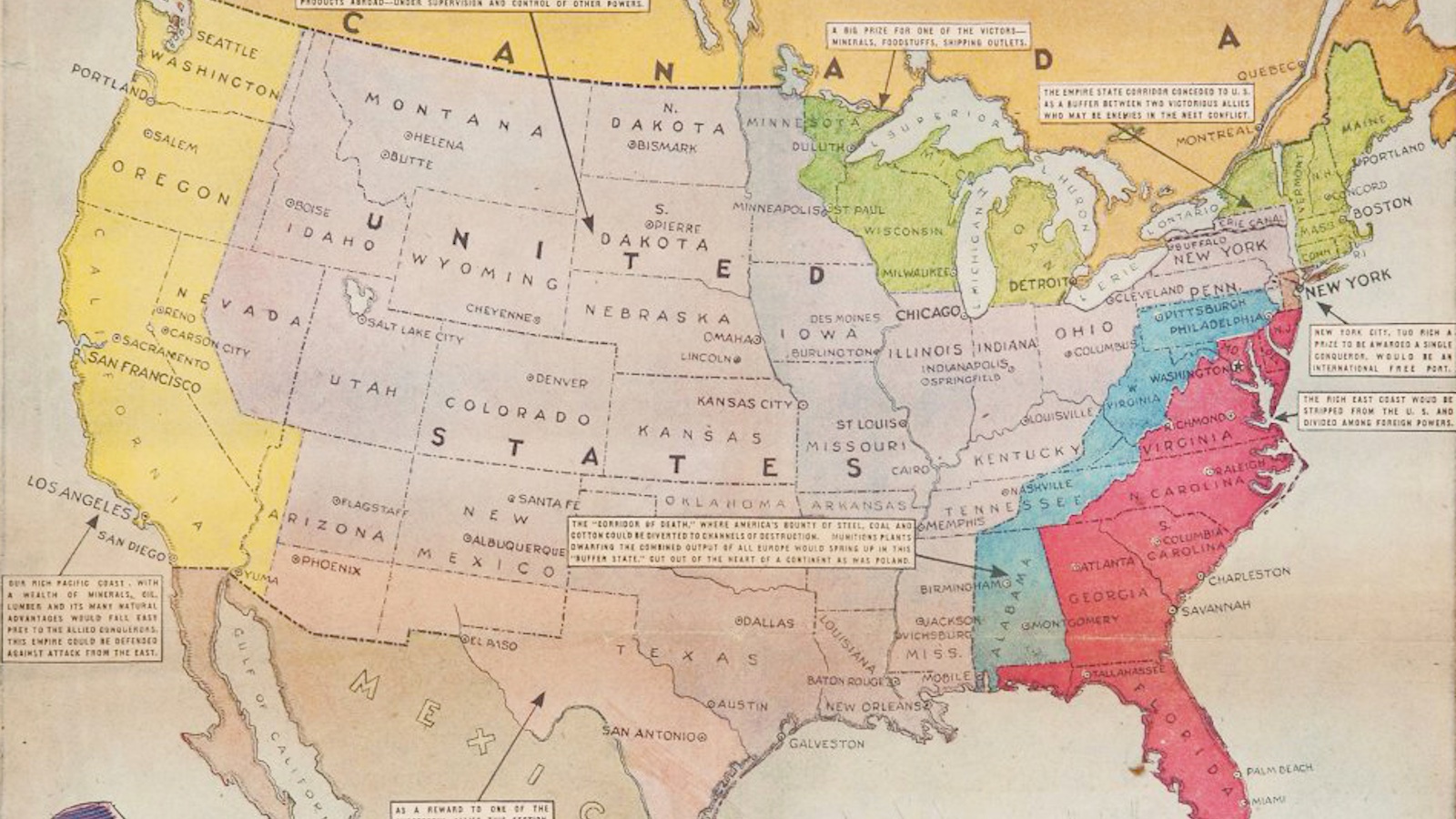

The American Revolution was just one theater in a world war. Although the Revolution had begun in 1775 as a small series of skirmishes between British troops and American militia at Lexington and Concord, Massachusetts, by the time of the siege of Yorktown, in 1781, Britain was becoming overwhelmed by the effort of fighting five separate nation-states around the globe—France, Spain, the United States, the Dutch Republic, and the Kingdom of Mysore, in India. Ultimately, it was the events in that wider, global war that led to America’s independence.

While the global extent of the Revolutionary War may be astonishing to Americans today, it was not surprising to Americans living at the time. Since their creation in the 1600s, the American colonies had been intimately involved in wars between England and other European powers, and their engagement in those wars increased with every new conflict. The period between 1689 and 1815 was dubbed the Second Hundred Years’ War by the British historian John Robert Seeley, and the name has stuck. It alludes to the original Hundred Years’ War, fought between England and France during the Middle Ages. Like that conflict, the Second Hundred Years’ War was primarily fought between the two great European powers of the day, France and England (Britain after its 1707 union with Scotland), but it also pulled in allies on both sides from across Europe and even from Asia. It was a series of eight wars rather than one long conflict, during which one out of every two years saw major hostilities between nations. Americans fought in every one of those wars.

The Second Hundred Years’ war differed from the first in that the belligerents were now colonial powers, and much of the conflict revolved around protecting and expanding their overseas empires. These European wars for dominance were increasingly fought on North American soil and with colonial American troops. The first of these, the War of the Grand Alliance (1689–97), erupted as France attempted to extend its borders into neighboring monarchies, an effort opposed by a coalition led by England and the Dutch Republic. In America, this war was known as King William’s War, and on American soil it primarily involved small companies of New England militia unsuccessfully attempting to invade French Canada and Acadia in response to cross-frontier raids.

Just four years later, after Spain’s King Carlos II had died without an heir, the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–14), called Queen Anne’s War in America, pitted the Hapsburg powers of Britain and Austria against the French Bourbon crown for control of the vast Spanish colonial empire. Although this war was fought primarily in Europe, British colonists were now engaged on two fronts in America: against Spanish Florida in the south, and against French Canada, Acadia, and Newfoundland in the north. The colonists organized and deployed far larger, more aggressive and more effective expeditions than they had previously done, and although they suffered many defeats, the efforts of the colonials ultimately won Britain important concessions that expanded its North American empire.

During the next three wars, American colonists were fully engaged in fighting. The combined War of Jenkins’ Ear and War of the Austrian Succession (1739–48, the latter known in America as King George’s War) saw American troops deployed overseas for the first time. In 1741, the four-thousand-strong American Regiment, under the overall command of the British admiral Edward Vernon, fought valiantly at the Battle of Cartagena de Indias (in modern-day Colombia), but lost to the defending Spanish troops. The American Regiment included a twenty-two-year-old infantry captain named Lawrence Washington, the older half-brother of George Washington, who would later name his estate Mount Vernon in honor of his admiral.

By the time the Revolutionary War began in 1775, the colonials had already experienced almost a century of British-European warfare

In 1745, the colonies of Massachusetts, Connecticut, and New Hampshire mounted an expeditionary force of four thousand troops that besieged and captured the French fortress at Louisbourg in Nova Scotia. The subsequent peace was short-lived: less than a decade later, George Washington—now a lieutenant colonel in the Virginia Militia—led an assault on a French scouting party at Jumonville Glen, in today’s Fayette County, Pennsylvania, which triggered the massive, globe-spanning Seven Years’ War (1754–63), known in America as the French and Indian War. Tens of thousands of colonists fought on the front lines against France and Native American nations in Ohio, New York, Canada, and Acadia. By the end of that war, France had ceded all its North American territories to Britain, and colonial Americans celebrated the victories with as much fervor as their British kin across the ocean.

In short, by the time the Revolutionary War began in 1775, the colonials had already experienced almost a century of British-European warfare, and they fully understood America’s role in wider wars around the world. For this reason, most colonials recognized that their own fight for independence against Britain would necessarily involve other European powers, notably France and Spain. As Arthur Lee, a colonial representative in London, told Benjamin Franklin in 1774, “America may yet owe her salvation [to European powers] should the contest be serious and lasting.” His brother Richard Henry Lee furthered this sentiment when he wrote to Patrick Henry in April 1776 that “a timely alliance with proper and willing powers in Europe” was needed to win the upcoming war. But he also noted that “no state in Europe will either treat or trade with us so long as we consider ourselves subjects of Great Britain.” For this reason, he argued, “It is not choice then, but necessity that calls for independence, as the only means by which foreign alliance can be obtained.”

Several weeks later, on June 7, 1776, Richard Henry Lee introduced a measure before the Second Continental Congress that called for a declaration of independence. The resulting document, approved on July 4, 1776, was in reality an engraved invitation to France and Spain to go into battle alongside the Americans. The declaration succeeded beyond the Americans’ wildest imaginings, for the Revolutionary War eventually drew hundreds of thousands of soldiers and sailors from nations across North America and around the globe to fight against their common enemy.