Cornell University program aims to end world hunger in 10 years

Credit: SIMON WOHLFAHRT/AFP via Getty Images)

- An international team of researchers has released a series of studies geared towards ending world hunger.

- They are thought to be some of the first people to use Evidence Synthesis for agricultural data.

- Their ideas could increase food production and lower poverty for a low cost, regardless if they meet their lofty goal.

World Hunger is one of those problems that everybody seems to want to solve but that just won’t go away. In 2020, nearly 700 million people suffered from hunger at some point.

This is despite years of both lip service to the idea of feeding everybody and sincere attempts by people, governments, and organizations with deep pockets to solve the issue. The number of people going hungry has been declining in recent years, but getting those last few hundred million fed has proven difficult.

A new project offers potential solutions that could finally feed the world. Ceres2030, named for the Roman Goddess of Agriculture, aims to help the world reach the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal No. 2 and end world hunger in ten years using evidence-based, targeted investments in various areas.

Headquartered at Cornell University, Ceres2030 is a collective project involving people from around the world. It is financed in part by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and the German Federal Ministry of Economic Cooperation and Development.

The enterprise includes more than 70 researchers from 23 different countries with the best information available on what works to reduce hunger. These researchers are divided into eight teams, each covering a separate subject area. Each group reviews the literature and combines it into a general review which can be used to inform policy decisions.

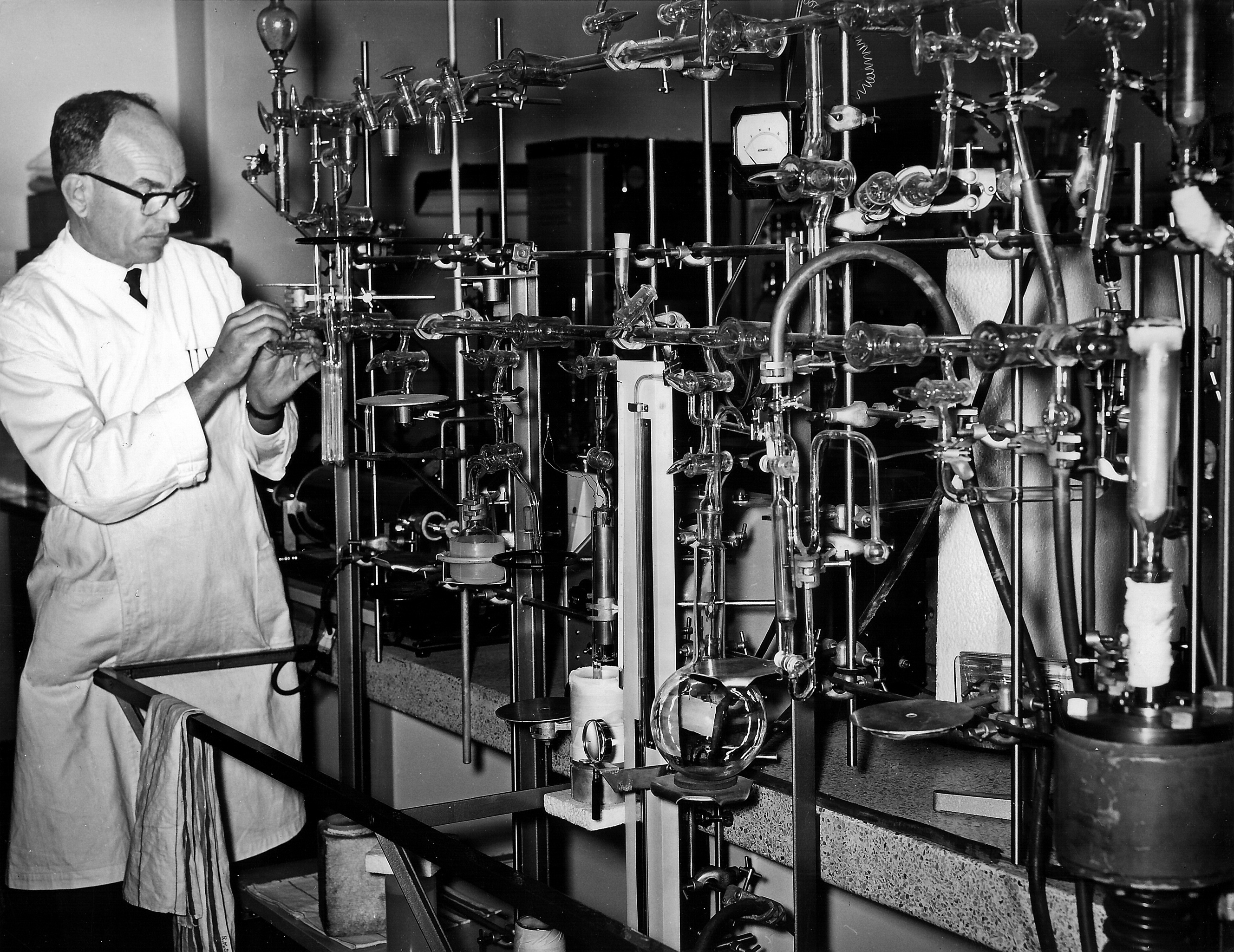

There exists a technique, frequently used in medical science and other health-related fields, called “Evidence Synthesis.” It aims to review all of the relevant literature on a topic in a way that outlines where the scientific consensus is, clearly shows where gaps in the research are, and provides a context for new discoveries. Before now, it was rarely, if ever, used to review information on agriculture.

Using AI to sort through the endless data, the project considered half a million previously published reports, studies, and articles searching for information. By reviewing the summaries of these documents, the machine was able to synthesize the findings. The humans involved with the project then took these findings and authored ten papers summarizing them to allow readers to draw broad conclusions on what the evidence suggests would effectively improve crop yields and farmer incomes.

This might strike you as a high tech version of an intensive review of the literature. However, it is essential to remember that many important works can sit unread for years at a time. Some of the studies reviewed may have been read by no more than a handful of people, and they certainly never reached the attention of farmers or officials in a place to apply their findings. By having computers go through this information, the Ceres team was able to create the most comprehensive summation of the data possible.

If humans alone were trying to do this task, they’d probably still be reviewing the data in 2030.

The analysis shows that many studies agree on the benefits of a few, straightforward initiatives. Among these findings are game-changing ideas like:

Farmer’s organizations help their members increase both their incomes and crop yields. Membership was linked with higher incomes in nearly 60 percent of studies, and benefits to crop yields were demonstrated in a quarter. These organizations play a part in helping farmers adopt modern techniques, tools, and crop types to help implement other policy suggestions. Assisting people in joining them can have a tremendous impact on their lives.

In the middle and lower-income countries, nearly three-quarters of small farmers live and work in areas where water is scarce. The vast majority of these farms do not have an irrigation system to speak of. Output and income could both be increased by addressing this infrastructure issue. Helping farmers switch to more climate change and drought-resistant crops and introduce new and improved livestock sources, both as sources of labor and food, can improve productivity and keep people resilient in the face of climate change.

These are just a handful of the ideas Ceres2030 endorse in their press releases. In each case, they point to piles of data showing the effectiveness of these ideas in increasing incomes, crop yields, and small producers’ resiliency in the face of threats such as climate change. It could cost roughly 14 billion dollars more a year in aid to do it, about twice as much as we are spending on the problem now, alongside new investments by the governments of nations most plagued by hunger.

All of these ideas can be implemented tomorrow; many places have already done these things. It is only a matter of deciding to do it. Some of the findings and ideas are even simpler than these, including discovering that we waste a lot of food and that simple solutions can prevent much of it.

More information on their ideas and how they came to their conclusions can be found on the Ceres2030 website.

It might.

The findings and recommendations are based on extensive research, histories of successful implementation elsewhere, and a sincere desire to use evidence to help people. Following them would lead to better-informed farmers making more money while sustainably growing more food. The recommendations are neither one-size-fits-all, nor are they overly specific to the point where they cannot be generalized.

There are also plenty of reasons to be pessimistic. A study published this year in Nature argues that we will not be able to end world hunger by 2030. It takes the stance that some countries with endemic malnourishment are unlikely to reach their development targets for 2025, let alone the more ambitious goals for 2030.

The costs of not at least making progress on this front are very high. Without progress, an additional 100 million people could end up both hungry and mired in extreme poverty by the end of the decade, according to an estimate by the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization. The COVID-19 pandemic has caused some regression already, as economic difficulty leads to empty bellies.

The entirety of human history has been marked by attempts to produce enough food for everybody, and it is only recently (relatively speaking) that we’ve managed to do that. Today, we grow enough food for 10 billion people but seem to have difficulty getting it to the people who need it most. The suggestions of the Ceres2030 team, if followed, offer the chance to finally rid the world of hunger and famine for less than $50 per currently malnourished person per year.

It’s only a question of doing it. Let’s see if we want to.