A Hackathon Reveals Most Any Hacker Can Break Into Election Equipment

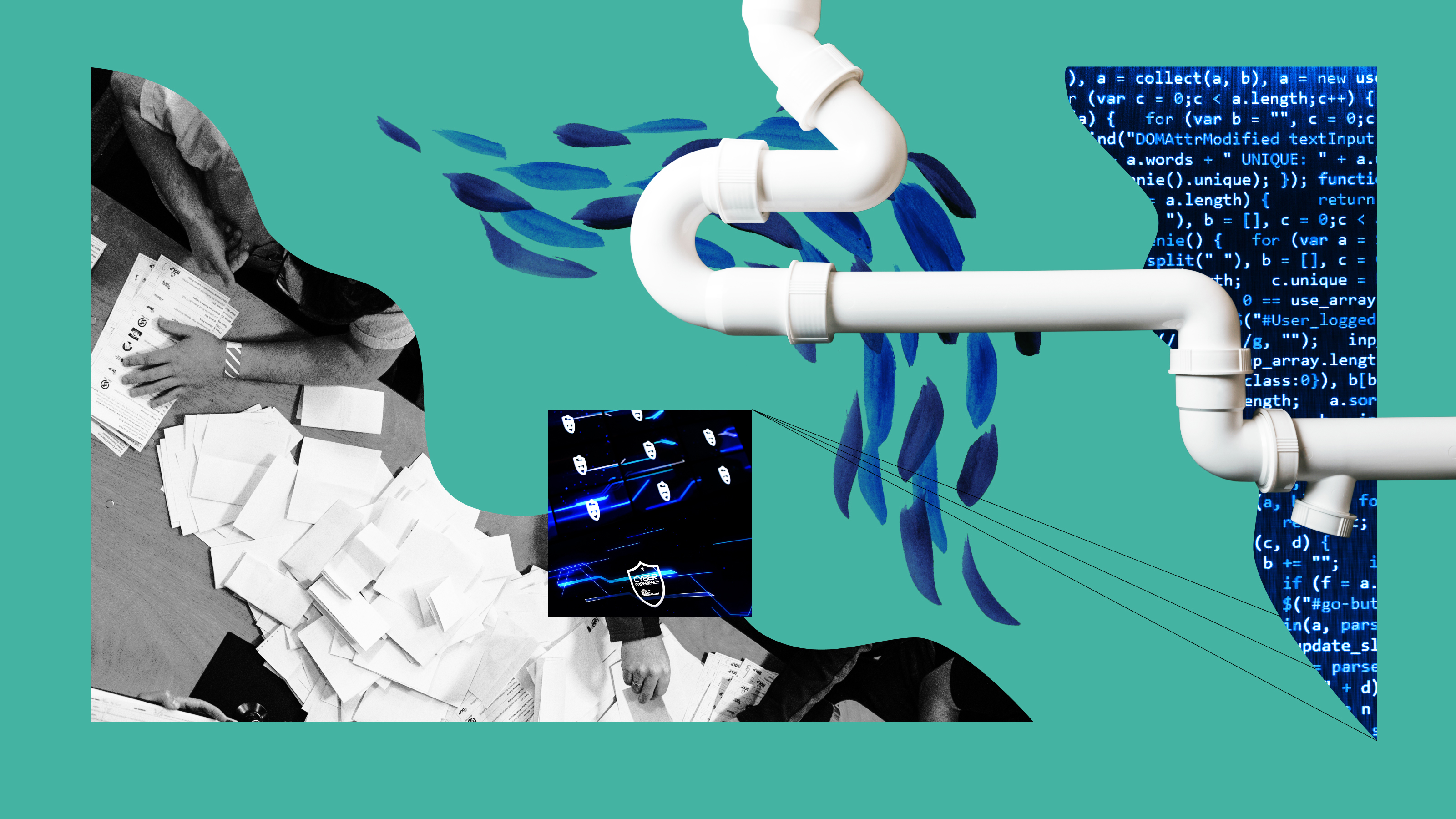

From July 27-30, 25,000 hackers — yes, you read that right — convened in Las Vegas for the DEFCON hacking conference. One of the topics under discussion was the security of U.S. voting systems, especially apt in light of ongoing investigations into possible Russian hacking of the American electoral system during the 2016 presidential election. At the conference, there was a gathering of voting hardware called “Voting Village” for hackers to check out and hack into, if they could. In September, DEFCON published the startling results of the Voting Village experiment at VerfiedVoting.org: Every single piece of voting hardware was successfully breached. The report was co-authored by DEFCON’s founder Jeff Moss.

Douglas E. Lute, former U.S. ambassador to NATO, and retired Lieutenant General of the U.S. Army wrote the preface to DEFCON’s report, explaining why he’s getting involved in electoral security:

The answer is simple: last year’s attack on America’s voting process is as serious a threat to our democracy as any I have ever seen in the last 40+ years — potentially more serious than any physical attack on our Nation. Loss of life and damage to property are tragic, but we are resilient and can recover. Losing confidence in the security of our voting process — the fundamental link between the American people and our government – could be much more damaging. In short, this is a serious national security issue that strikes at the core of our democracy.

In fact, what happened at Voting Village was even worse that it seems, since the hackers didn’t even possess the resources and tools a real-world hacker might have, such as “source code, operational data or other proprietary information,” according to the report. And it didn’t require any special skill, either; hackers of all levels broke in just fine.

Most of the equipment was purchased on eBay, though DEFCON has a special allowance that allows it to buy machines for research. Most current voting machines are made by just four manufacturers. All in all, there were 25 machines in Voting Village, including these:

The DEFCON report reveals how stunningly weak the U.S. voting system is, with bold text added for emphasis:

The first voting machine to fall — an AVS WinVote model — was hacked andtaken control of remotely in a matter of minutes, using a vulnerability from 2003, meaning that for the entire time this machine was used from 2003-2014 it could be completely controlled remotely,allowing changing votes, observing who voters voted for, andshutting down the systemor otherwise incapacitating it.

That same machine was found to have anunchangeable, universal default password — found with a simple Google search — of “admin” and “abcde.“

Virginia has decertified the AVS Winvote. VERFIEDVOTING)

An “electronic poll book”, the Diebold ExpressPoll 5000, used to check in voters at the polls, was found to have been improperly decommissioned withlive voter file datastill on the system; this data should have been securely removed from the device before reselling or recycling it. The unencrypted file contained thepersonal information— including home residential addresses, which are very sensitive pieces of information for certain segments of society including judges, law enforcement officers, and domestic violence victims — for 654,517 voters from Shelby County, Tennessee, circa 2008.

As important as the integrity of our election system is, the truth is it’s a patchwork of rules and systems individually acquired and operated by each state in accordance with the first clause in Article 1, Section 4 of the U.S. Constitution.

Local politicians have been able to, for example, maintain their hold on power by preventing their opponents’ constituency from voting. This has been done through literacy tests at the polling place, as well with the distribution of misleading information that’s prevented voters from successfully casting ballots. Today, photo IDs are required in some states that make voting harder for certain groups — often, the only photo ID available locally is a drivers license — disproportionately affecting students, the poor, and the elderly. And there’s always the question of incompetence that can result in ballots that make no sense to local voters or even to election officials during counting. Congress has modified national election laws only a few times to rectify egregious abuses, such as with the passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965 and the National Voter Registration Act of 1993.

All of which is to say that each state decides not only how its citizens will vote, but what kind of electoral machinery will be used. Whether or not the state has the requisite expertise or personnel on hand to select the best equipment, operate it, and keep it up-to-date and secure, that’s the way it works. Budgetary considerations at times drive state election officials simply to find and take the best deal available — regardless of potential conflicts of interest or other considerations — or force them to keep machines in service long after they should be de-certified and decommissioned. States don’t have the resources to thoroughly research the source of their machines’ components either, meaning that, as DEFCON notes, “the extensive use of foreign-made computer parts… within the machines opened up a serious set of concerns that are very relevant in other areas of national security and critical infrastructure: the ability of malicious actors to hack our democracy remotely, and well before it could be detected. “

Election consultant Pam Smith tellsWho.What.Why, “The very notion that local election officials would be able to protect themselves, when they are underfunded and under-resourced, is almost laughable.”

Five states — Delaware, Georgia, Louisiana, New Jersey and South Carolina — have chosen to forgo paper backups of voters’ choices, and nine others are partially paperless. Paper backup is a critical line of defense when dealing with otherwise completely electronic Direct Recording Electronic (DRE) machines, viewed by cybersecurity experts as the most vulnerable systems, not to mention likely to experience occasional operational failures.

The now-established certainty that Russia compromised our electoral systems in the elections of 2016 — though the full effect of their incursions is not yet known as of this writing — makes it clear that in our interconnected world, electoral security needs to be considered an issue of national security and no longer left to individual states. As Lute writes, “First, Russia has demonstrated successfully that they can use cyber tools against the US election process. This is not an academic theory; it is not hypothetical; it is real. This is a proven, credible threat. Russia is not going away. They will learn lessons from 2016 and try again. Also, others are watching. If Russia can attack our election, so can others: Iran, North Korea, ISIS, or even criminal or extremist groups.” Gen. Michael Hayden has said he suspects Russia’s Vladimir Putin must be pleased: “He wants to bring us down in the eyes of ourselves and of his people.”

Some state-level politicians will undoubtedly be reluctant to cede control over their election systems; we can expect to hear concerns voiced about “big government” whether in the context of it being an too-powerful controlling force on one hand, or, on the other, being incapable of doing it competently. There are currently state-level efforts under way to address the gaping security holes, and we can, at the very least, encourage these endeavors.

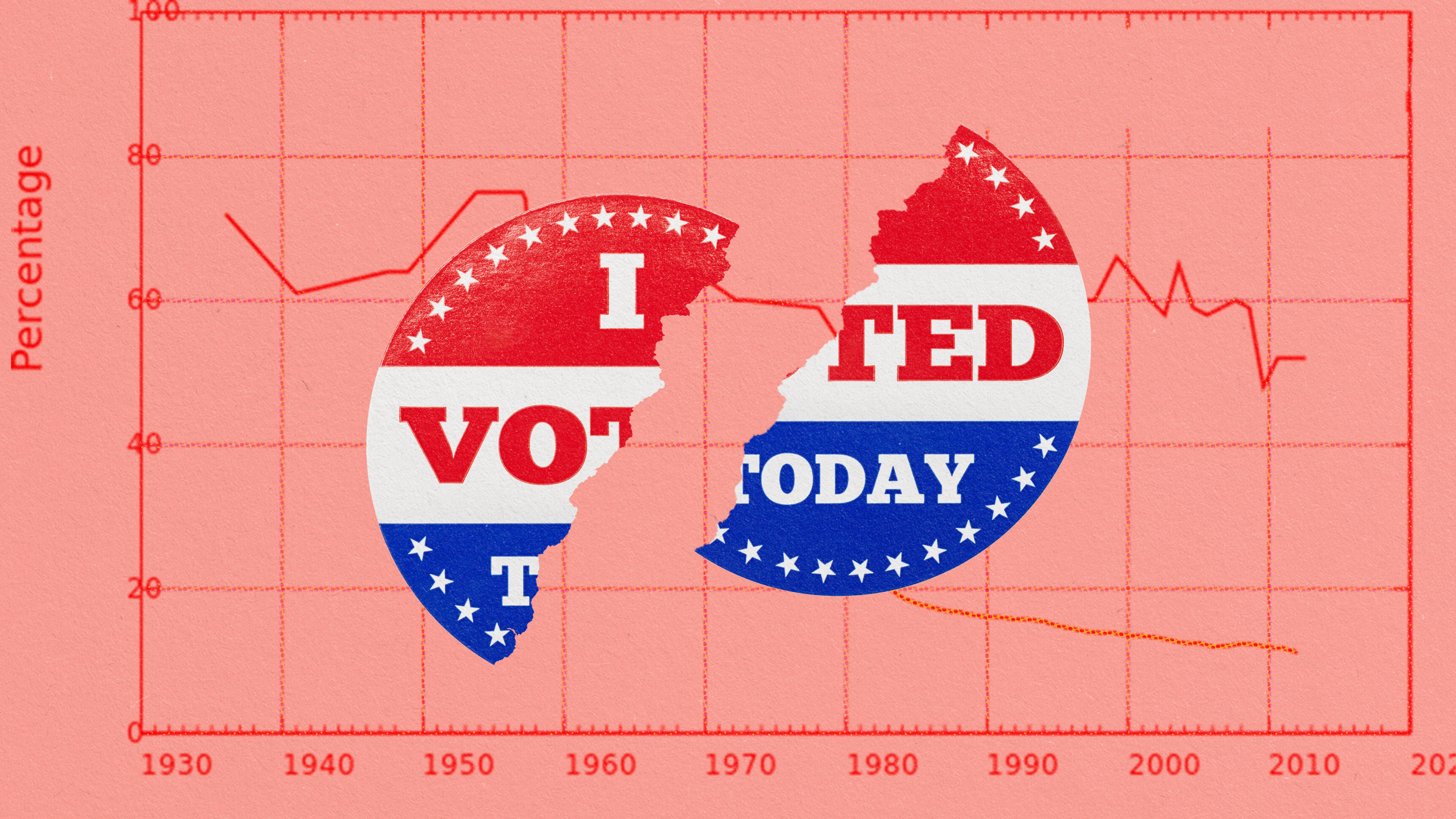

But belief in our democracy is something we’re on the verge of losing altogether. Even before the 2016 election, doubt was in the air, and sSince then faith in the honesty of U.S. elections has dropped precipitously.

(GALLUP)

Given how unlikely it is that hackers bent on destruction have slacked off, though, the sooner we can secure our systems, the better. It may be something only the Federal government can do. We’ll have to watch closely from here on in.