#17: Let Prisoners Vote

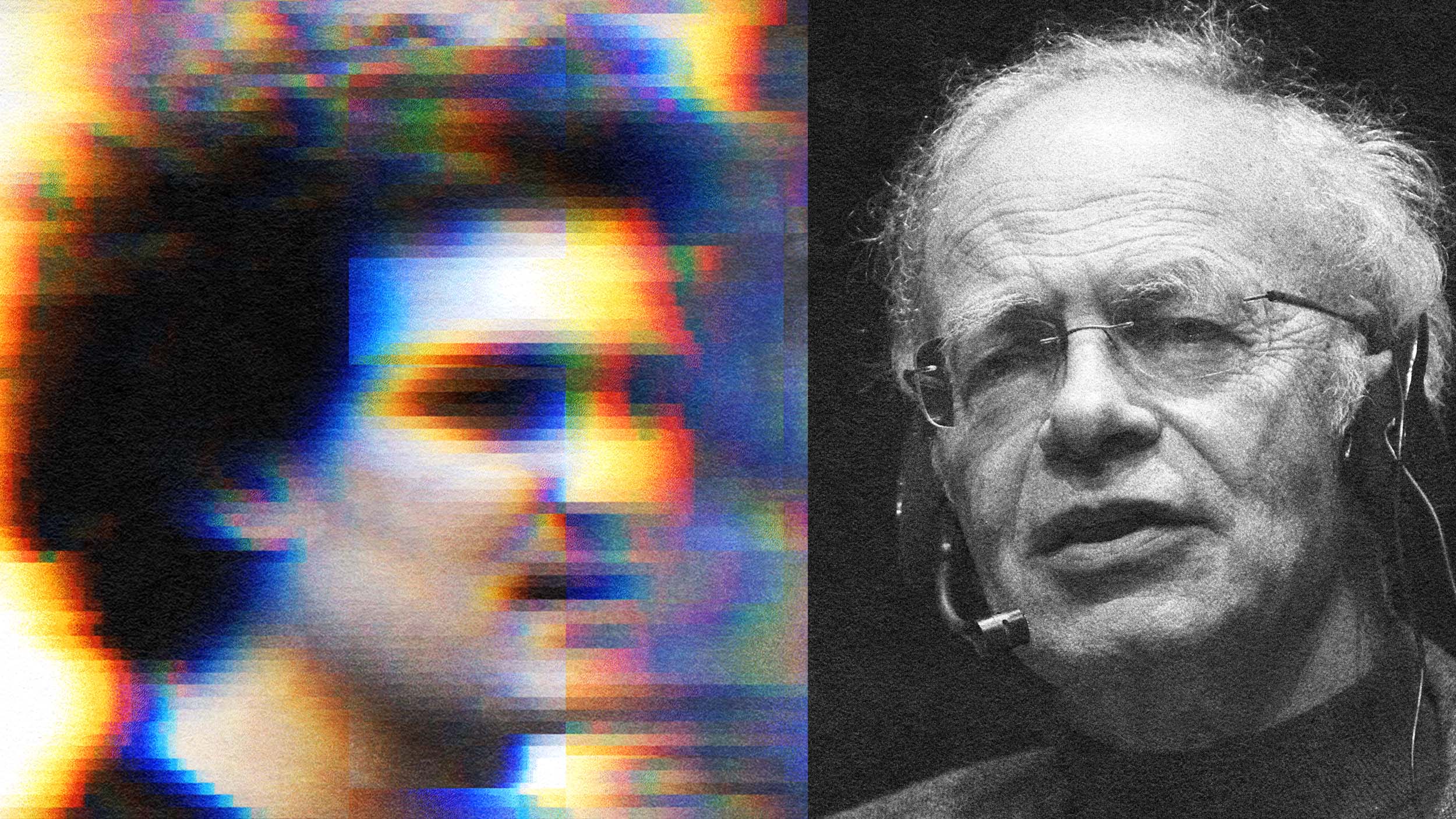

Ohio State University law professor Douglas A. Berman says everyone affected by society’s laws ought to have a right to vote—even if they have to mail in their ballot from the big house.

There are currently 2.3 million disenfranchised inmates in the United States: 1.5 million are serving prison sentences of over a year; 800,000 are locked in local jails serving sentences of a year or less; and roughly 100,000 still have the right to vote, but have not made bail and cannot make it the polls while awaiting sentencing.

According to a report co-published by Human Rights Watch and The Sentencing Project, a national organization working for a fair and effective criminal justice system, disenfranchisement laws are “a vestige of medieval times when offenders were banished from the community and suffered ‘civil death.’ Brought from Europe to the colonies, these laws gained new political salience at the end the nineteenth century when disgruntled whites in a number of Southern states adopted them and other ostensibly race-neutral voting restrictions in an effort to exclude blacks from the vote.”

Though Berman agrees that disenfranchisement laws disproportionately affect racial minorities, his argument is founded on a more fundamental belief. “The right to participate in the political process flows from being subject to the laws, rules and regulations that political process sets forth,” says Berman, “Prisoners are in some sense being subjected to those rules and regulations in a more severe way than those who vote—in some ways they’re even more affected by our legal system—therefore they should have the right to fully partake in the political process.”

Berman’s advocacy of inmate enfranchisement is also driven by his instinct that historical expansions of the franchise—whether to African-American men in 1870 or to women in 1920—have in hindsight never been perceived as a mistake. Generally, he feels that expanding the franchise is beneficial to democracy. If Berman had his way, voting rights would also be extended to children as young as 10 years old. “My nine-year-old strikes me as a lot more political knowledgeable than a lot of adults I deal with on a regular basis,” he says.

Granting prisoners the right to vote would present states with some additional administrative duties, but the burden might not be so bad. Every inmate in the United States has the right to send and receive mail. Instead of setting up traditional polling places where prisoners would get to “pull the lever,” Berman says states could set up a vote-by-mail system similar to that used in Oregon, where all elections have been held by mail since 1998. Critics of the vote-by-mail system argue that it eliminates the communal experience of voting on Election Day. It is unlikely this would present an issue for inmates who feel they have already been eliminated from the community through their disenfranchisement.

The Takeaway

In the Presidential Election of 2000, George W. Bush bested Al Gore after receiving just 537 more votes to take to the electorate in Florida. To underscore the possible impact of allowing prisoners to vote, in 2000 there were exactly 71,319 disenfranchised prisoners in the state of Florida.

Why We Should Reject This

“If you’re not willing to follow the law then you can’t claim to the right to make the law for everyone else,” says Roger Clegg, the President and General Counsel of the Center for Equal Opportunity. Clegg recently testified before the House Judiciary Committee’s Subcommittee on the Constitution, Civil Rights, and Civil Liberties to challenge the “Democracy Restoration Act,” a bill proposed by Michigan Representative John Conyers (Dem.) that aims to secure Federal voting rights of people who have been released from incarceration.

In addition to defending the rights of states to decide who may or may not vote, Clegg firmly believes that people who are in prison have not met a certain set of objective standards that bar other people, such as non-citizens and children, from voting. “We don’t let everyone vote. We don’t let children vote, we don’t let non-citizens vote, and we don’t let criminals vote,” says Clegg, “and the common denominator there is that we have certain minimum objective standards of responsibility, trustworthiness, and loyalty to the political system that people must meet before they participate in this sacred enterprise of government.”

More Resources

— Professor Douglas A. Berman’s Mortiz College of Law Homepage

— The Sentencing Project: “A national organization working for a fair and effective criminal justice system by promoting reforms in sentencing law and practice, and alternatives to incarceration.”

— “Voting Behind Bars,” New York Times/Opinionator article by Linda Greenhouse

— The Center for Equal Opportunity: “A think tank devoted exclusively to the promotion of colorblind equal opportunity and racial harmony.”

— Bureau of Justice Statistics