Did psychedelic mushrooms and group sex play a role in human evolution?

Photo credit: Kseniya Avimova / AFP / GettyImages

Psychedelic drugs “expand” one’s mind: this is how many people describe the changes in sensory experiences elicited by psychotropic drugs. A psychedelic trip can be good or bad, but it ultimately ends once the drug’s effects wear off. According to the American ethnobotanist Terence McKenna, however, psilocybin-containing “magic” mushrooms had a profound and lasting influence on the course of human evolution.

“The great embarrassment to evolutionary theory is the human neocortex,” says McKenna. He argues that there is no explanation for how such a major organ was dramatically transformed in complexity in a narrow window of time to create the jump from hominids to humans.

What lit “the fire of intelligence”? McKenna’s answer lies in the hominid’s diet. He essentially thinks that “we ate our way to higher consciousness.”

McKenna’s “Stoned Ape” theory of human evolution breaks the process into three stages. In stage one, around 40 to 50 thousand years ago, early hominids in Africa, like Homo Erectus, were forced to abandon their canopy-dwelling lifestyle due to the desertification of the African continent. As they were forced to find new sources of food, they followed herds of wild cattle in whose dung they found insects that became part of their diet. Also in the dung were magic mushrooms that often grow in such environments.

As they started to eat these mushrooms in low doses, early hominids improved their visuals acuity and became betters hunters and survivors, giving them an advantage over those who did not consume the shrooms.

Stage Two of how the psilocybin diet impacted the human brain under McKenna’s theory took place 20 to 10 thousand years ago, as hominids discovered the aphrodisiac qualities of ingesting the shrooms. According to McKenna, at higher doses, the mushrooms caused increased male potency and led to group sexual activities. “Everyone would get loaded around the campfire and hump in an enormous writhing heap,” half-jokingly posits McKenna.

Causing greater genetic diversification, these orgies also had the effect of creating the first societies, where males could not trace paternity and as such did not identify children as personal “property,” raising them as a community.

These orgiastic sessions also led to the development of symbolic functions in hominid cognitive abilities via early art creation and dance.

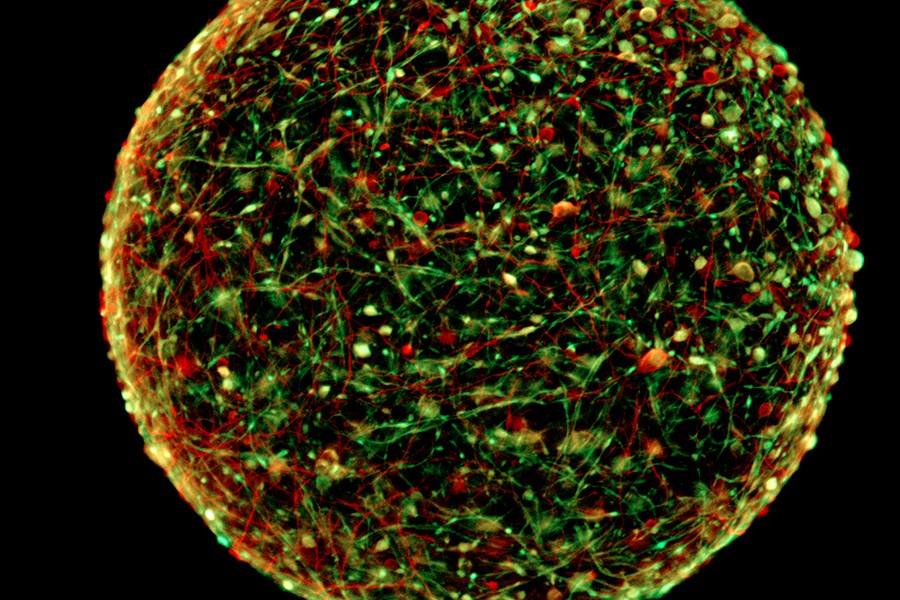

The last stage of how psychedelics changed the brain came from taking higher doses of the mushrooms. McKenna argued that when doses doubled, psilocybin affected the language-forming region of the brain, causing vocalizations that became the raw material for the evolution of language. This also led to the first human religious impulse.

Challenges to McKenna’s theories have mainly revolved around the lack of evidence for a number of his assertions. Many scientists have dismissed his ideas as “a story” rather than an explanation based on proven facts. Yet, there has been a growing amount of evidence about the lives of early hominids that provides some corroboration to McKenna’s work.

In particular, evidence has been found that Stone Age humans ate mushrooms. German anthropologists discovered mushroom spores on the teeth of a prehistoric woman who lived around 18,700 years ago.

In 2015, the Spanish anthropologist Professor Guerra-Doce published a paper outlining the use of hallucinogenic plants by early humans. Additionally, Neolithic and Bronze cave paintings that resembled psilocybin mushrooms were found in the Italian Alps and in Villar del Humo in Cuenca, Spain.

Cave paintings that feature a row of mushroom-like objects from Villar del Humo, Cuenca, Spain. CREDIT: Giorgio Samorini

Psilocybin mushrooms.