The trouble with medicating mental illness

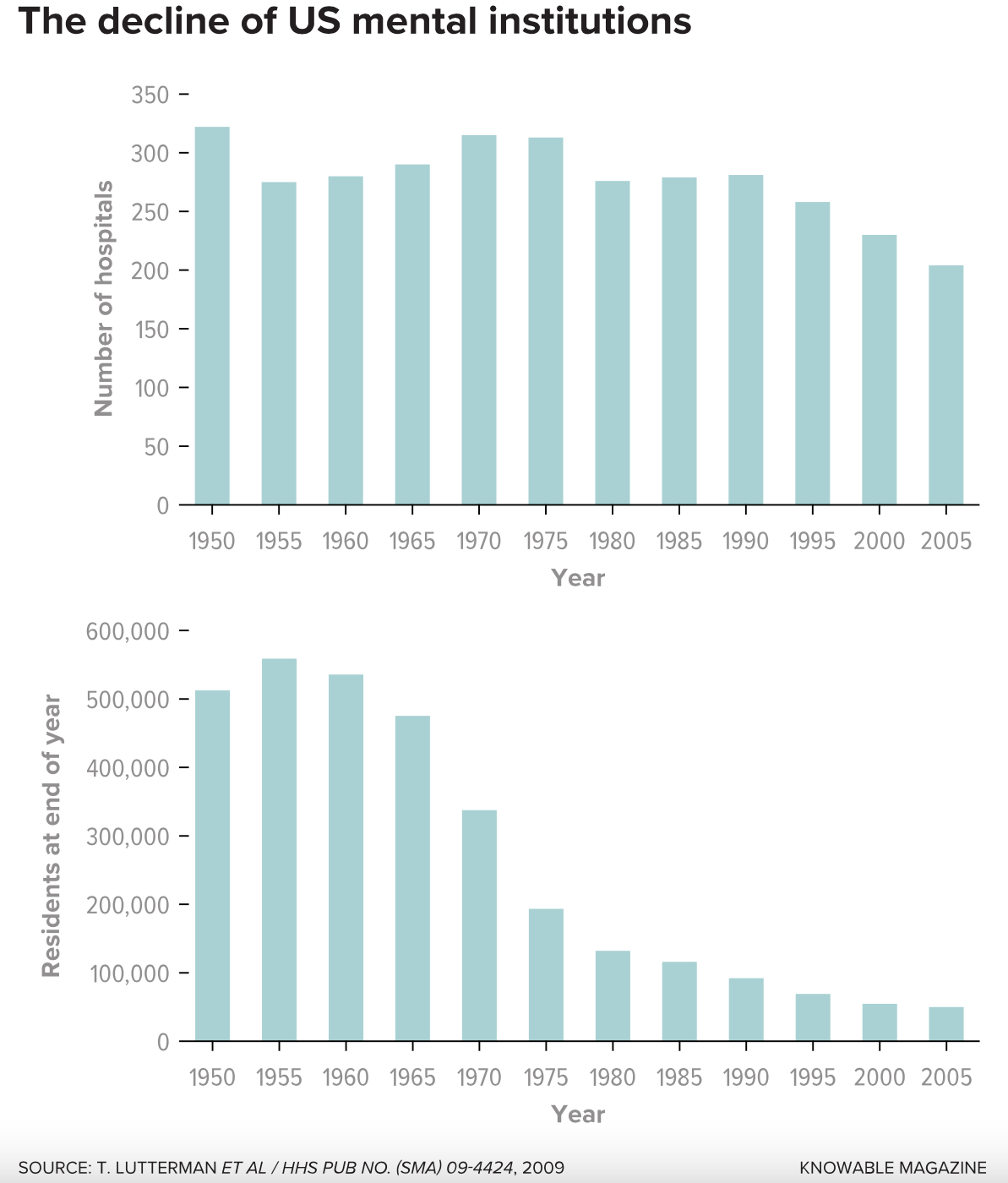

The standard of care for the severely mentally ill in the United States has drastically changed since the 1950s, when more than half a million patients resided in enormous state hospitals. As pharmaceutical firms developed new antipsychotic medications, national policy shifted such that most of the old hospitals have now closed. Today, the majority of US patients, even those with serious mental illnesses such as schizophrenia, bipolar syndrome and major depression, receive only short-term, in-patient medical treatment to quell symptoms before being sent home.

The old asylums were the scenes of some well-publicized abuses and poor conditions. Yet their closures and the parallel embrace of medications did not solve the issue of how to best care for people. The current mental-health system leaves many mentally ill patients no better off, says Joel Braslow, a historian and psychiatrist at the University of California, Los Angeles. In some cases, the situation has grown worse.

In the 2019 Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, Braslow and UCLA colleague Stephen Marder argue that our current “age of psychopharmacology” has shrunk society’s sense of responsibility toward the mentally ill. Whereas most psychiatrists once viewed mental illness as a complex interaction between a patient’s biology and social context, Braslow and Marder contend, it is now often seen more narrowly as merely symptoms to be medicated.

Braslow blames this shift for what he calls our society’s “total failure” in caring for its most vulnerable members: Roughly 140,000 seriously mentally ill people are now homeless on city streets, while 350,000 others are serving time in prisons and jails, where their illnesses get little treatment.

Knowable Magazine spoke with Braslow about the history of this transformation and what it would take to better serve the multitudes of people living with psychiatric problems.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Why do you call this the “age of psychopharmacology”?

I think about it in two different but interrelated ways. First, it underlines our growing reliance on drugs to treat disorders of the mind. Today, one in six Americans takes a psychoactive drug. This has reinforced the idea that the drugs treat specific diseases, much like insulin treats diabetes. For example, Tipper Gore (the ex-wife of former Vice President Al Gore) has explained her own depression as a chemical imbalance, with her brain running out of serotonin like a car runs out of gas. This description implies that depression has both a specific cause — in her case, depleted serotonin — and a specific cure, a drug.

Secondly, there’s our shrinking vision of what causes psychiatric disease and what we can do clinically for those who suffer from it. Prior to the late 1960s and 1970s, American psychiatrists tended to take a more expansive view. Today’s greater focus on the individual and a simple model of disease has helped justify the belief that drugs or psychotherapies hold the key to alleviating psychiatric disease. However, this view ignores the fundamental nature of psychiatric disease as simultaneously biological, psychological and social.

What accounts for this shift?

Psychoactive drugs have been used since the 19th century, but they were generally regarded as little more than sedatives — referred to as “chemical straitjackets.” The chance discovery of the major classes of psychotropic drugs in the 1950s changed the status of psychopharmacology. These new compounds did more than simply sedate; they actually treated many of the symptoms of psychiatric disease, such as hallucinations, depressed mood and disordered thoughts.

However — and this is a crucial point — throughout the 1950s and much of the 1960s, psychiatrists largely saw psychotropic drugs as just one part of an overall regimen, a part that neither dominated nor defined the nature of the disease and its treatment. Psychiatrists continued to see psychiatric disease in a holistic manner, in which symptoms could involve an individual’s failure to function in the social world and their inner torment. Treatment remained similarly expansive, especially when the illness warranted state hospitalization.

Things changed dramatically from the 1970s onward. It’s tempting to attribute this to the drugs’ effectiveness, but this is simply not the case. There has been little change in the actual efficacy of antidepressants, antipsychotics and anti-anxiety drugs over the last half-century. Social, economic and cultural circumstances did far more to bring on the age of psychopharmacology than did the effectiveness of the drugs themselves.

For one thing, psychiatric hospital administrators came under increasing pressure to decrease their hospitalized patient population. Hospital records from the 1970s show doctors under pressure to discharge patients earlier and earlier. So physicians, understandably, focused on symptoms that could be quickly and easily treated, and relied increasingly on drugs as their primary intervention. Under such circumstances, it became more and more impossible to address the thornier problems of how the patients functioned in the world.

You write that this change was also influenced by politics?

Yes. For nearly 150 years, state governments believed that society and physicians had a moral responsibility to provide care for all those afflicted with mental illness. But beginning in the late 1960s and 1970s, the welfare state came under increasing attack with the belief that individuals needed to take individual responsibility for themselves. State governments were primarily responsible for the smooth running of market economies and not for individual welfare. The elections of Ronald Reagan in the US and Margaret Thatcher in the UK underlined this shift in political culture.

These changes shifted care priorities away from state hospitals and toward care in the community. But that has become increasingly fragmented, decentralized and subject to the logic of market forces rather than to the needs of those with serious mental illness.

The political ideology that emphasizes individual responsibility fits neatly with a belief that disease is largely a problem of biology and/or psychology and that the solution is a treatment that focuses on the individual’s psychology or biology.

Given that we’re relying more on medications, how well do they actually work?

That’s a difficult question to answer. Take schizophrenia, for example. We don’t have a good understanding of the causes of what are likely multiple different kinds of schizophrenia, but there’s a growing belief that antipsychotic drugs can do little for the fundamental symptoms of apathy, social withdrawal and cognitive deficits. These drugs do, however, treat other symptoms — hearing voices, speaking incoherently and behaving in an agitated way.

We have good evidence that antipsychotic drugs help prevent relapse in the short run, although the jury is still out whether someone should be on antipsychotic drugs for a lifetime. So, yes, they work, but only with a number of important caveats. I think the same could also be said for antidepressant drugs.

You write that the medical system’s increasing reliance on randomized controlled trials helped fuel the shift toward drugs. Is the problem that it’s somehow easier to test medications than psychotherapies?

The short answer to that is yes.

A randomized controlled trial requires easily measurable variables and, consequently, has shifted our understanding towards an increasingly reductionistic view of psychiatric disease that excludes many of the social and psychological realities. It encourages us to think in terms of specific interventions, such as psychotropic drugs, that treat a specific, discrete disease, just like antibiotics treat bacterial infections. This way of thinking fails to accommodate the complex social and psychological deficits intrinsic to psychiatric disease.

How have the patients fared with these changes?

Despite good intentions, advances in neuroscience and an increasingly large number of psychotropic drugs, those afflicted with serious mental illness have not done well. Overall, outcomes such as mortality and social function have worsened for the vast majority with serious mental illness. You can see it in the unprecedented population of mentally ill homeless people — 60,000 just in Los Angeles. We’re allowing people who are disabled by psychosis to languish in the streets. This wouldn’t happen with cardiac patients.

And a lot of those homeless people end up in jail.

True. Today there are about 5,000 seriously mentally ill people in the Los Angeles County jail. I have a hard time going to the jail myself — it’s such a horrible place. Many of the sickest patients refuse medications, often exacerbating their psychotic symptoms. The sheriff has little recourse but to house the most psychotic, non-compliant inmates in isolation, so as to be the least disruptive to the other inmates and guards.

About a thousand inmates are in solitary confinement, in individual Plexiglas cells for 23 hours a day. At the same time, these terribly psychotic individuals are left to disrobe, smear feces and a variety of other psychotic symptoms that worsen under conditions of isolation and deprivation. Any time they’re out of their cells, they are almost invariably shackled, even while seeing a psychiatrist. It’s heartbreakingly sad.

So how should society respond? Do we need to go back to the asylums of the past?

I think we need to learn from the positive aspects of asylum care. Rather than either reestablishing the asylums or intensifying the alienation and neglect of the last 50 years, we need to come up with new, evidence-based ways of caring for those with serious mental illness.

Once we acknowledge the reality of mental illness as a disease that robs its victims of meaning, social connections and the ability to function in contemporary society, we can start designing interventions that address this reality. We cannot simply wish away the complexity of psychiatric disease and the kinds of interventions that are necessary for humane, scientifically based care.

This article originally appeared in Knowable Magazine, a nonprofit publication dedicated to making scientific knowledge accessible to all. Sign up for Knowable Magazine’s newsletter.