Radicalization: The strange psychology behind fusing yourself with one cause

- The philosopher Simone de Beauvoir once wrote about the “Serious Man” — a type of person who commits so much of themselves to one project or cause that they dissolve their identity.

- She speculated that these people were dangerous. A recent study from the University of Texas proves just this: People like the Serious Man are more likely to “self-sacrifice” for a cause.

- The study suggests that the best way to deradicalize someone is to have them expand the causes and beliefs they commit to — to go beyond only one identity.

You do not have only one name and identity, but rather many simultaneously. At this moment, you could be an employee, a father, a best friend, a client, a Steelers fan, a Democrat, a Christian, and a vegetarian all at the same time. Your personality swings like a pendulum between identities depending on time, place, and social context. We each possess a deck of cards containing tarot-like pictures and titles, ready to be played at the opportune moment.

But for some people, one of these labels or identities comes to dominate all others. Some people let their entire self become consumed by some cause or belief.

This process has been described not only by psychologists seeking to understand how people become radicalized by ideology, but also by philosophers like Simone de Beauvoir, whose Ethics of Ambiguity overviews a dangerous archetype of person called the Serious Man.

The Serious Man

Imagine you’re at a party, happily chatting to a stranger who’s easygoing, funny, and intelligent. You’re having a great time. In passing, you make an offhand joke about Marxism. Suddenly, the entire mood shifts. The stranger frowns and tenses up.

“Why would you say that?” he says.

You laugh nervously.

“You think this is funny?!”

Congratulations! You’ve just met a “Serious Man” — a common yet dangerous type of person, according to de Beauvoir.

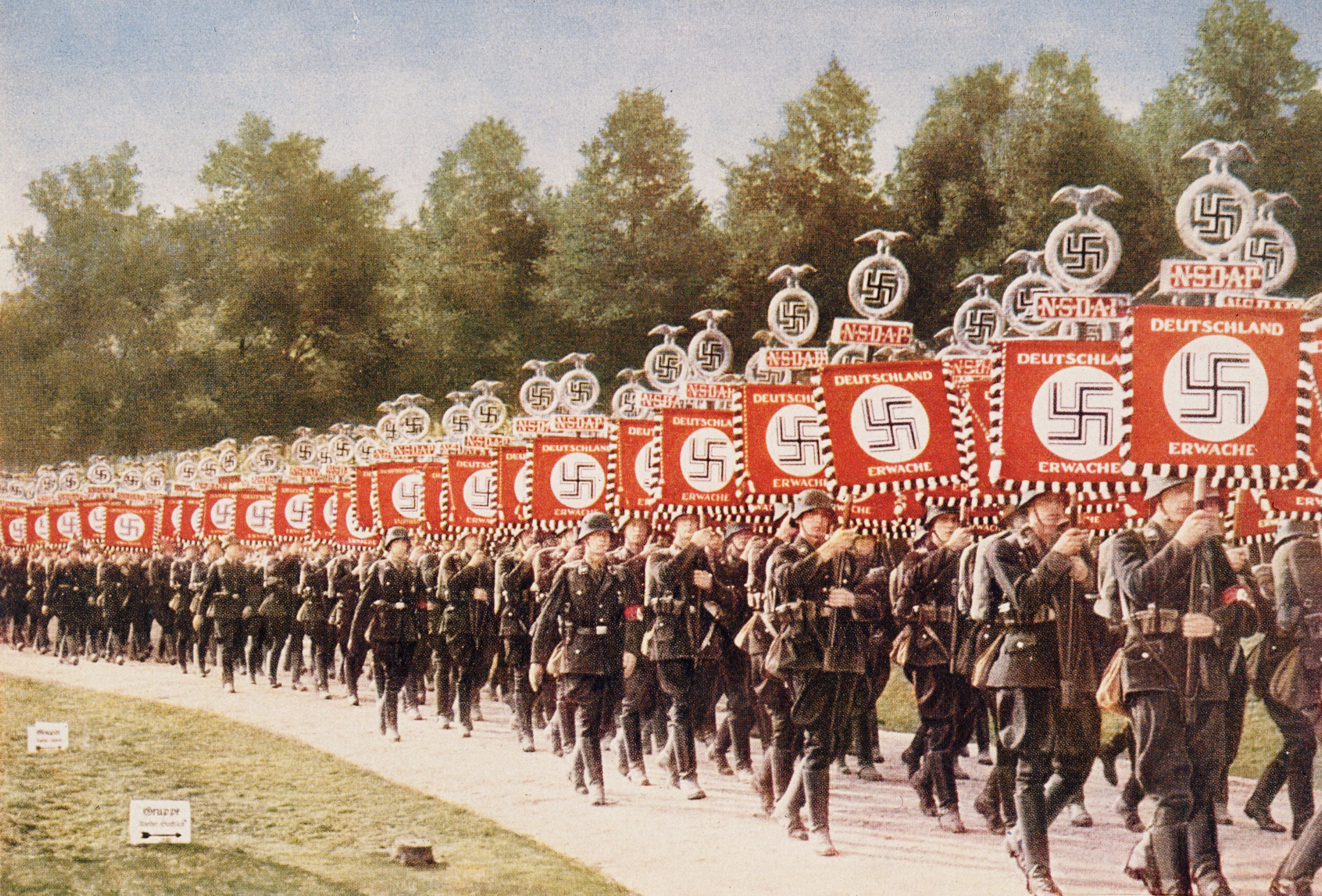

The Serious Man is someone who takes one ideology or belief so unimaginably seriously that they consider it beyond question — a sacred thing that should definitely never be mocked. The Serious Man could be a Christian, communist, capitalist, or anyone, really. In each case, some belief is raised up to the “stature of an idol,” and everyone must take this idol seriously. There is no greater thing than this!

De Beauvoir noted, with irony, how easily the Serious Man mocks others’ idols. The atheist scoffs at the believer. The Marxist rolls their eyes at the capitalist. The old cynic laughs at the young romantic. It’s quite okay to ridicule others’ seriousness, but never one’s own.

The issue comes in how much of oneself the Serious Man invests in these idols. When he puts all his eggs into one basket, he becomes dependent on it. His identity tied to it, he “falls into a state of preoccupation.” Everything is seen as a potential threat to his idol.

The Serious Man is a dangerous man. He won’t hesitate to sacrifice anything — everything — to protect or serve his idol. He ignores the value of other people because he sees his idol as the only “unconditional value.” Everything must bow before this god. Human life, freedom, and identity will always be second.

Winston Churchill once said, “A fanatic is one who can’t change his mind and won’t change the subject.” What better way to describe De Beauvoir’s Serious Man? At best, they can be a dull and broken record. At worst, they have the homicidal fanaticism that only unbending ideology can give us.

The road to fanaticism

A recent study published in Frontiers in Psychology bolstered what De Beauvoir described in her Ethics of Ambiguity. The researchers set out to reveal the dominant factor in determining whether someone would commit to “self-sacrifice,” or, in other words, figure out why someone would choose to die for a cause. The team focused on three variables: moral convictions, sacred values, and a phenomenon called identity fusion.

“Identity fusion occurs when an abstraction (a group, cause, or even another person) comes to define the self,” the authors noted. “When people become fused to a target group or cause, the boundaries between the self and the target become porous and the personal self becomes one with the target. This union creates a sense of equivalence of the self and the target that makes defending the target equivalent to defending the self. As a result, strongly fused persons are especially prone to enact pro-group or pro-cause behaviors when under threat from perceived adversaries.”

While all three variables were strong predictors of self-sacrifice, identity fusion was consistently the strongest of the three. The study found that those who fuse their identity so intensely with a belief or conviction amount to being “radicals-in-waiting.” It makes sense, of course. If you come to see yourself as inseparable from some ideal or grouping, then you also cannot imagine yourself existing as without those. Therefore, the more your identity is fused with a cause, the more likely you are to die for that cause.

Get more complicated

What Martel et al. go on to argue is that the best way to combat extremism and to fight radicalization is to have those at risk try to pursue other causes and identity beliefs.

“Based on our research, we believe that shifting radicals from fusion with an extremist cause to a benevolent cause may transform them from a force of evil to a force of good,” the authors wrote.

When people reduce their entire personality to one thing, they are willing to risk everything for that thing. But when we are more complex — when we embrace many identities — we are much more likely to interact with life in all its vibrant, multifaceted complexity. The way to deradicalize is to make your life more complicated — to fuse many parts of our selves with many parts of the world.

Jonny Thomson teaches philosophy in Oxford. He runs a popular Instagram account called Mini Philosophy (@philosophyminis). His first book is Mini Philosophy: A Small Book of Big Ideas.