Why 1960s psychiatrists started the anti-psychiatry movement

- Anti-psychiatry is a broad movement against psychiatry. While in the past, adherents leveled reasonable critiques against psychiatry, today many call for psychiatry itself to be abolished.

- Critiques from anti-psychiatry academics helped psychiatry to become more empirical and responsive to patients. Today, psychiatry utilizes medicinal, lifestyle, and psychological treatments.

- While psychiatry can still improve, anti-psychiatry’s modern arguments against the profession fall flat.

In 1965, the prominent Scottish psychiatrist R.D. Laing launched a radical experiment. At London’s Kingsley Hall, Laing founded a community for the mentally ill that stood in stark contrast to the institutions and asylums that had grown prevalent in the developed world. Psychotics, schizophrenics, and other seriously mentally ill persons would not be locked up, treated with drugs, or lobotomized. Instead, they would be allowed to live as their authentic selves, partake in communal therapy sessions, and even use the psychedelic LSD. This was a voluntary program. Residents could leave whenever they liked.

Underneath this unorthodox approach lay a critique that both challenged the fundamental principles of psychiatry and had lasting consequences on mental health care practices.

The origins of the anti-psychiatry movement

Today, Laing’s experiment is considered an offshoot of the “anti-psychiatry” movement (though Laing himself never liked the term). Laing, and other psychiatrists like Thomas Szasz, David Cooper, and Franco Basaglia, questioned the diagnoses of certain mental illnesses, shunned the drug- and surgery-centered treatments of the time, and demanded reform of the asylum system, which often institutionalized individuals against their will.

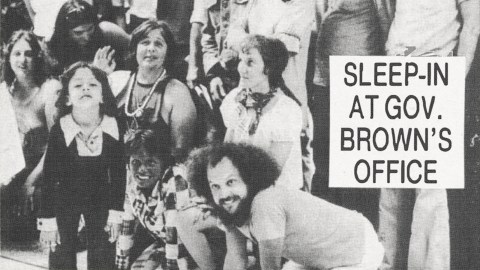

A popular idea that emerged during this time held that most mental illnesses were not actual diseases with neurobiological underpinnings, but rather social constructs, or “problems in living,” as Szasz described them. In the 1960s and 1970s, the counterculture movement was largely receptive to this framing of mental illness, partly because it viewed psychiatry as an attempt to exert control over people who didn’t conform to social norms. Stories of chaotic, overcrowded, and abuse-filled institutions littered the newspapers. The novel and subsequent Academy Award-winning film One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest dramatized the plight of institutionalized persons. Thus, partly as a result of the anti-psychiatry movement, state mental facilities and asylums were shut down en masse beginning in the 1960s, an initiative called deinstitutionalization.

Anti-psychiatry was born mostly as a critique of mainstream psychiatry of the 20th century, which no doubt had flaws. Lately, however, some linked to the movement have taken it to the extreme, claiming that mental illness doesn’t exist, that anti-psychotic medications are universally harmful, and that psychiatry itself should end as a profession. These views primarily find their footing in the conspiratorial corners of social media and YouTube, but they also have backing from more powerful sources such as the Church of Scientology, whose adherents tout the organization’s pseudoscientific (and expensive) treatments for people in poor mental health.

“They also bankroll a Los Angeles museum called Psychiatry: Industry of Death, probably the only museum in the world dedicated to attacking a medical specialty,” Rob Whitley, an associate professor in the Department of Psychiatry at McGill University, noted in a 2012 paper.

Anti-psychiatry today is more akin to the anti-vaccine movement, says Dr. Joe Pierre, a Health Sciences Clinical Professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at the University of California, San Francisco. While original critiques of psychiatry focused on the asylum system and over-reliance on powerful anti-psychotic medication, both of which he agrees needed reform, today they zero in on the profession’s link to the pharmaceutical industry, accusing psychiatrists of keeping their patients medicated to sate the greed of “Big Pharma.”

A straw-man argument

However, Pierre writes, the anti-psychiatry crowd today is fighting against a straw man. Psychiatry is not what it was a half-century ago. For one, researchers today have a better (though still incomplete) understanding of the neurobiological underpinnings of mental illnesses. What’s more, while psychiatrists still do occasionally institutionalize people against their will, the practice is far rarer than it used to be. Moreover, psychiatrists recommend evidence-based interventions like psychotherapy, exercise, sleep, and proper diet to help their patients, in addition to modern medications, which, by the way, have a compelling record of success in placebo-controlled trials.

There’s no question that psychiatry can still improve, he told VICE’s Shayla Love in an interview.

“We need safer and more effective interventions to treat people with mental illness. We need to better understand, and educate the public about, when medications are more helpful and when they are less so. We need to get closer to diagnoses that are validated by explanatory biological pathophysiologies. We need to reform mental health care throughout the world to destigmatize mental illness and provide more compassionate care.”

But today’s followers of anti-psychiatry are less interested in legitimate critique and more interested in burning the profession to the ground. Unfortunately, their prescription — putting psychiatrists out of a job — will undoubtedly harm far more people than it will ever help.

After all, just look what happened in Kingsley Hall, mentioned at the beginning of this piece. In short, it was chaos. The place frequently attracted drifters. A few housemates smeared the walls with their feces. At least two people jumped off the roof.

In short, anti-psychiatry’s answer to mental illness is anarchy.