That know-it-all who drives you crazy? They’re full of it, says science.

Do you know someone who claims to be THE source on one particular thing, be it politics, religion, relationships, or etiquette? There are movies, music, and sports know-it-alls too. No matter the kind, few people can be quite as irksome. Want to stick it to the know-it-all in your life? Just casually mention that they seem to suffer from “belief-superiority.” Then hit them with this study, out of the University of Michigan. It says that know-it-alls tend to over-inflate what they know.

Although we all do this to some degree, and studies have shown that it’s actually hard for us to judge exactly what we do know, some people take their sense of being knowledgeable to the extreme. Researchers ran six studies focusing on politics. They wanted to answer these questions: “Do people who think that their beliefs are superior have more knowledge about the issues they feel superior about? And do belief-superior people use superior strategies when seeking out new knowledge?”

What they found was, even when faced with holes in their understanding, know-it-alls still claimed to be more knowledgeable than their peers and even sought out information to confirm their bias, while ignoring data which made them appear wrong or less savvy. The study’s findings were published in the Journal ofExperimental Social Psychology.

The research consisted of quizzes testing knowledge on political terms and issues. Many contained both true terms and made up ones. Just like you’re average music know-it-all who says they recognize a band they’ve never heard of, so too did political know-it-alls say they were familiar with terms that didn’t exist. In one experiment, participants were told beforehand that some of the terms were made up. Belief-superior people still selected fake terms and insisted they knew them.

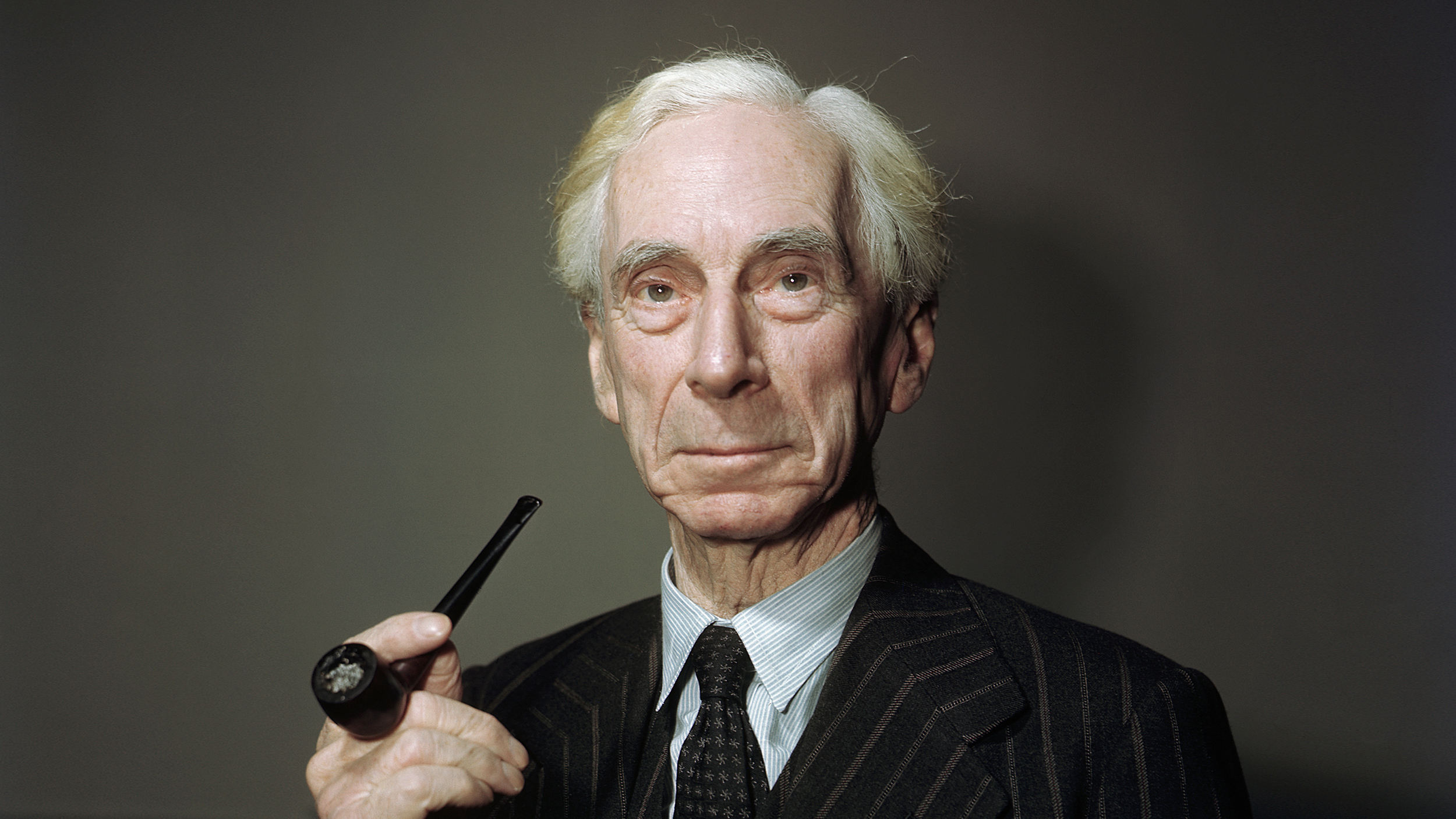

Psychologists say most belief-superiors are underneath it all insecure. They feel a compulsive need to appear as if they know everything. Sometimes under that though, they harbor deeper feelings of superiority. Credit: Bastian, Day 264. Flickr.

Michael Hall was the lead author of the study. He’s a psychology graduate student at the university. “Whereas more humble participants sometimes even underestimated their knowledge, the belief superior tended to think they knew a lot more than they actually did.”

This is reminiscent of the quote by British philosopher Betrand Russell, “The whole problem with the world is that fools and fanatics are always so certain of themselves, but wiser people so full of doubts.” Psychologists call this the Dunning-Kruger effect and a number of studies have supported it.

In one part of the quiz, participants were asked to read one of two articles on a controversial topic. In half of these, respondents read essays which agreed with their point of view. In the other, they got ones that disagreed. “We thought that if belief-superior people showed a tendency to seek out a balanced set of information,” Hall said, “they might be able to claim that they arrived at their belief superiority through reasoned, critical thinking about both sides of the issue.”

Instead, know-it-alls were far more likely to choose data that supported their beliefs and ignore things that contradicted them. This phenomenon not only over-inflates what belief-superior people actually know, it causes them to miss opportunities to genuinely improve their knowledge base.

Despite it all, there is hope for the know-it-all. Credit: Sage Ross. Self-Portrait, Pretentious. Flickr.

All of us shy away from information that confirms opposing viewpoints to a certain extent. Belief-superior people do this to a far greater degree, researchers say. These are usually tied to more significant parts of our identity, such as our values. Kaitlin Raimi is a U-M assistant professor of public policy. She was the study’s co-author.

Raimi said in a press release, “Having your beliefs validated feels good, whereas having your beliefs challenged creates discomfort, and this discomfort generally increases when your beliefs are strongly held and important to you.” What’s really interesting is, as the researcher’s wrote in their study, “When belief superiority is lowered, people attend to information they may have previously regarded as inferior.” So there is hope for the know-it-all, if you can break past their defenses. But that’ll be a tough shell to crack.

To learn more about the Dunning-Kruger effect, click here: