How do 80-year-old ‘super-agers’ have the brains of 20-somethings?

Photo by Angelina Litvin on Unsplash

- “Super-agers” seem to escape the decline in cognitive function that affects most of the elderly population.

- New research suggests this is because of higher functional connectivity in key brain networks.

- It’s not clear what the specific reason for this is, but research has uncovered several activities that encourage greater brain health in old age.

At some point in our 20s or 30s, something starts to change in our brains. They begin to shrink a little bit. The myelin that insulates our nerves begins to lose some of its integrity. Fewer and fewer chemical messages get sent as our brains make fewer neurotransmitters.

As we get older, these processes increase. Brain weight decreases by about 5 percent per decade after 40. The frontal lobe and hippocampus — areas related to memory encoding — begin to shrink mainly around 60 or 70. But this is just an unfortunate reality; you can’t always be young, and things will begin to break down eventually. That’s part of the reason why some individuals think that we should all hope for a life that ends by 75, before the worst effects of time sink in.

But this might be a touch premature. Some lucky individuals seem to resist these destructive forces working on our brains. In cognitive tests, these 80-year-old “super-agers” perform just as well as individuals in their 20s.

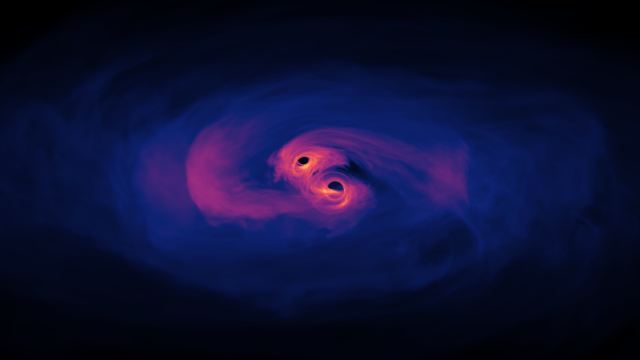

An image of the brain highlighting the regions associated with the default mode network.

Wikimedia Commons

Just as sharp as the whippersnappers

To find out what’s behind the phenomenon of super-agers, researchers conducted a study examining the brains and cognitive performances of two groups: 41 young adults between the ages of 18 and 35 and 40 older adults between the ages of 60 and 80.

First, the researchers administered a series of cognitive tests, like the California Verbal Learning Test (CVLT) and the Trail Making Test (TMT). Seventeen members of the older group scored at or above the mean scores of the younger group. That is, these 17 could be considered super-agers, performing at the same level as the younger study participants. Aside from these individuals, members of the older group tended to perform less well on the cognitive tests. Then, the researchers scanned all participants’ brains in an fMRI, paying special attention to two portions of the brain: the default mode network and the salience network.

The default mode network is, as its name might suggest, a series of brain regions that are active by default — when we’re not engaged in a task, they tend to show higher levels of activity. It also appears to be very related to thinking about one’s self, thinking about others, as well as aspects of memory and thinking about the future.

The salience network is another network of brain regions, so named because it appears deeply linked to detecting and integrating salient emotional and sensory stimuli. (In neuroscience, saliency refers to how much an item “sticks out”). Both of these networks are also extremely important to overall cognitive function, and in super-agers, the activity in these networks was more coordinated than in their peers.

How to ensure brain health in old age

While prior research has identified some genetic influences on how “gracefully” the brain ages, there are likely activities that can encourage brain health. “We hope to identify things we can prescribe for people that would help them be more like a superager,” said Bradford Dickerson, one of the researchers in this study, in a statement. “It’s not as likely to be a pill as more likely to be recommendations for lifestyle, diet, and exercise. That’s one of the long-term goals of this study — to try to help people become superagers if they want to.”

To date, there is some preliminary evidence of ways that you can keep your brain younger longer. For instance, more education and a cognitively demanding job predicts having higher cognitive abilities in old age. Generally speaking, the adage of “use it or lose it” appears to hold true; having a cognitively active lifestyle helps to protect your brain in old age. So, it might be tempting to fill your golden years with beer and reruns of CSI, but it’s unlikely to help you keep your edge.

Aside from these intuitive ways to keep your brain healthy, regular exercise appears to boost cognitive health in old age, as Dickinson mentioned. Diet is also a protective factor, especially for diets delivering omega-3 fatty acids (which can be found in fish oil), polyphenols (found in dark chocolate!), vitamin D (egg yolks and sunlight), and the B vitamins (meat, eggs, and legumes). There’s also evidence that having a healthy social life in old age can protect against cognitive decline.

For many, the physical decline associated with old age is an expected side effect of a life well-lived. But the idea that our intellect will also degrade can be a much scarier reality. Fortunately, the existence of super-agers shows that at the very least, we don’t have to accept cognitive decline without a fight.