Neurotechnology today: What’s real, what’s coming

Image source: Luca del Puppo

- A new film, I AM HUMAN, takes a comprehensive look at the realities of neurotechnology today.

- The film follows three patients for whom experimental treatment may be the best option.

- Experts weigh in on the difficulties and the promise of neurotech.

We hear a lot these days about a coming convergence between man and machine. Nowhere are more promises being made than in the area of the brain. From Elon Musk’s brain interface to the promise of enhanced minds to home-brewed brain “stimulators,” neurotechnology seems poised to carry us across a threshold into a new and glorious world. Or a new and terrifying one. There’s robust debate over the potential impact, dangers, and value of such disruptive technology, as there should be. The problem is that we’re not so good at thoughtful, reasonable debate.

We don’t often write on Big Think about individual movies, but there’s a new one, I AM HUMAN, directed and produced by Taryn Southern and Elena Gaby. It provides an unusually intelligent, wide-ranging, and balanced overview of where the research stands, and it’s a compelling and thought-provoking experience. This being an area of such keen interest to Big Think readers, we recommend being on the lookout for this film.

Bill, Anne, and Stephen

One of the great hopes for brain research, of course, is that we’ll discover the mechanisms behind brain disorders and learn how they can be cured. The World Health Organization has estimated that about 1 in 6 people have a brain disorder of some sort — that’s a billion-plus people. As our visionaries fuel our imaginations regarding the eventual possibilities, it’s easy to forget there are people here and now for whom the restorative potential of brain technology is no sci-fi daydream — it’s a source of hope that their health can be restored. As doctors and technicians embark on this journey, they’re accompanied by people you’d never imagine meeting at the cutting edge. People for whom such wildly experimental therapies are their best, and maybe only, hope.

I AM HUMAN introduces us to three such people. It’s in following them through their procedures that we see the latest technologies being explored. Our emotional investment in this brave trio viscerally reminds us of the stakes involved.

- Bill recalls, “I was riding a bicycle in a charity event. It was raining really badly and I was following a mail truck. And then all of a sudden, it stopped and I didn’t.” A tetraplegic, Bill has no feeling below his mid-chest and longs to be able to one day regain enough movement simply to feed himself without assistance.

- Anne has Parkinson’s disease. “I’m not really sure what’s happening in my brain. Anxiety. Insomnia. Paralysis,” says Anne. In addition to her fear of becoming nothing but a burden to her family as her symptoms worsen, “One of the Parkinson’s symptoms I was always afraid of was that you couldn’t smile and when you smiled you had a stony expression,” she says. “It’s hard to connect with people. I’m just way too exhausted and way too disorganized mentally to be with people the way I used to.”

- Stephen was born with a condition he knew nothing about until his world world turned white: ” When I lost my vision, the whole world collapsed.” He lives alone, aided by his sister, with whom he’s close, helping him get through life. “I just miss being independent.”

Connective ports provide access to electrodes implanted in Bill’s brain.

Image source: Luca del Puppo

The challenge of the human brain

None of the many experts interviewed in I AM HUMAN believe that a fundamental understanding is imminent of that three-pound object that has so much to do with who we are. Southern tells Big Think that, “The one consistent thing I’ve learned about a lot of neuroscientists is they have a very sober and humble view of just how complex and difficult of a problem they are tackling.”

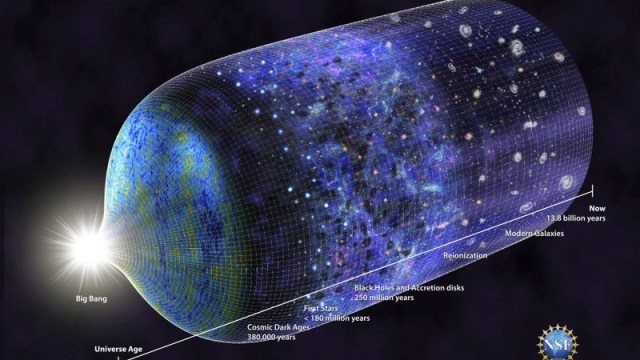

The current estimate is that the brain contains 100 billions neurons. As neuroscientist Miguel Nicolelis notes, “100 billion was the old estimate of the number of galaxies in the universe.” And even that number doesn’t convey the true mathematical complexity involved. David Eagleman, also a neuroscientist, says that each of those neurons “is as complicated as the city of Los Angeles. It’s connecting to 10,000 of its neighbors — so you have, you know, 500 trillion connections” to identify if you’re trying to understand the human brain. Computer scientist Ramez Naam says it simply: “The brain is the most complicated object we’ve ever encountered in nature.”

It’s also a black box. Alongside each movement we make are lightning-fast instructions exchanged between these many neurons in some internal language we don’t speak. Researchers use a range of technologies to eavesdrop on the brain’s chatter — as Southern says, “You have methods like EEG, which uses electrical impulses to read brain activity; deep-brain electrodes also use electricity. But then you’ve got magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to read blood flow and sound waves through ultrasound. Of course, the non-invasive methods are more palatable. I’m sure that soon in the future, neuroscientists will see all of our methods now as crude.”

Just as daunting, when neuroscientists attempt to manipulate individual neurons, the precision required is astounding, with each procedure a white-knuckle procedure. Surgeon Andres Lozano tells the filmmakers, “This is a game where you have to be within one millimeter. That one millimeter means a difference between success and failure.”

Or stumbling into another area of the brain. One doctor told the filmmakers of a case in which an interface was implanted into the hypothalamus of a patient weighing 420 pounds “to see if they could regulate hunger or appetite.” No dice. On the other hand, “To their surprise, the patient had vivid flashes of memory from 30 years earlier. When they left the stimulator on for a period of time, at a lower current, the patient had huge increases in memory capacity and being able to remember lists of words.”

So for all of the fever-dreams of any-time-now cyber-brains, neurotech investor Bryan Johnson offers a reality check: “It’s extraordinarily difficult to make breakthroughs in neuroscience. Scientists are tackling these really complicated problems, trying to do things that other people consider to be impossible. And it makes it both an extremely exciting time but also, it’s daunting because there is no clear path to success.”

Anne must remain conscious during her deep brain surgery.

Image source: Joel Froome, ACS

Visions of the neurotech future

The film presents’ a range of advocates’ visions of the possibilities should we finally be able to master the workings of the brain.

“We are about to enter into the most consequential revolution in the history of the human race,” says Johnson, “where we can take control of our cognitive evolution. If we can make breakthroughs in the brain, we can overcome our biological limitations. We can reject the things that stop us from moving forward. My hope is that we get to a point in tech advancement that we’re not limited by our technology, we’re empowered by it, so it’s a matter of choice of what we want to become.”

While Southern says coverage of research is often focused on the enhancement of people to be “smarter, better, faster,” she suggests that this may merely be a reflection of “our own sort-of Western bias to favor productivity and efficiency. But perhaps in other Eastern cultures they would orient the use of an interface to induce greater states of calm or create more empathy.”

Johnson offers up how this could work: “Imagine I had a tool to interface with my brain where I could walk a mile in someone else’s shoes. What if I could feel what it was like to be you? What if I could understand your contextual framework? What if I understand your memories and your emotions? Would that change the way we deal with each other? The way we cooperate, the way we make decisions?” Or, he adds, “Would that change our creative ability?”

Retinal implants such as Stephen’s are created in Second Sight’s lab in Sylmar, CA.

Image source: Credit: Joel Froome, ACS

Philosophical question arise

Of course, not everyone is embracing neurotechnology. According to a recent Pew study for example, people are more worried than enthusiastic when it comes to brain chip implants designed to boost a person’s natural abilities — only 34% would be interested in getting one. (About half are okay with implants’ use for therapeutic value.)

It’s not just a fear of change — there are genuine philosophical and ethical issues. As Naam says in the film, “As we have this ability to change who we are, change our personality, what’s at the core of us? What does that do to our sense of where we belong in the universe?”

Professor of philosophy and law Nita Farahany sums up the question this way: “If we start tinkering with the brain, if we start changing it….What does that mean? Are we about to fundamentally change what it means to be human? And if so, are we okay with that?” Seeing that, “We’re at the moment where there are a lot of very rapidly emerging technologies, and brain computer interfaces are starting to become part of mainstream society,”‘ she warns that we’d better start figuring out where we want all this research to go before it’s too late.

Southern tells us, “My biggest concern around the ethics is the lack of basic knowledge that we have as a society about science and tech. Scientists are so great at science, but sometimes lack the time or ability to connect that information to a larger audience. I think information is power, and the first step is education.”

As far as the ethics of experimenting on living patients goes, the decisions of Bill, Anne, and Stephen to participate reflect their lack of better options. “People are worried, you know, ‘Will I be the same, coming out, as I was going in?'” says Lozano. “There’s a tremendous amount of anxiety about whether they are going to change in their outlook, in their personality, in their motivation, in their drive. You know, this is brain surgery. It’s invasive. It is a scary thought.”

The doctors involved, says Southern, are “incredibly conscientious about the impact of their work on the world, and those that we worked with on the film have a real drive to help people and improve lives. I don’t think many people would argue that restoring function to someone with a disease as a resort of a brain interface is a bad thing. The ethical questions come down the road from there, when adoption becomes more widespread and normalized and people start to seek ‘cosmetic’ applications of these currently medical devices.”

In the end

Southern says she was drawn to this topic as a storyteller. “I see what they’re doing, and I think it’s just incredible.” Her goal in making I AM HUMAN she says, is that, “It’s their job to be understated, and my job to hopefully translate the awe and I wonder I feel about what they’re doing with the world.”

In their experiences creating this film, Southern and Gaby gained a uniquely comprehensive overview of where things stand. We asked Southern what she dreams of humanity gaining from neurotechnology. “I’m really intrigued by the ideas of expanding our sensory abilities and processing. We know that our brains receive data through our given senses — sight, tough, taste, sound, etc. But that data isn’t necessarily reflective of reality, and other animals can receive data into their brains differently. For instance, bats have a sense called echolocation that allows them to use sound waves and echoes to determine where they are in space. What if we had that ability? Or what if we could sense electromagnetic waves or ultraviolet light? I’d be pretty excited to see some of these things come to fruition.”

Such capabilities could allow us to understand the true nature of physical reality in ways we currently lack the tools to even image. On a more day-to-day level, she adds, “I’d also love to just be able to turn off that pesky and unnecessary fight-or-flight survival response to mundane stress.”

The experience has left Southern feeling “Optimistic. Every new technology has been fraught with incredible advantages and drawbacks. I see this being no different. We’re just so often uncomfortable with changing the status quo — but ultimately we collectively adopt what is valuable to us. Pessimism around technology,” she says, may just reflect issues with our values and systems. “When the foundation of those are broken, it’s hard to imagine not building things on top that wreak some degree of havoc. Ultimately, however, having our ability to see and understand the mechanics of our own minds — the creation force of our reality — offers us unparalleled potential beyond our wildest imaginations.”

I AM HUMAN will be screened at the Tribeca Film Festival in early May.