Empathy Can Be Hazardous to Your Health, Finds Study

Feeling empathetic towards the suffering of others, be it just a friend going through a bad time or hurricane victims, is an essential part of what makes us human. But empathy can also be hazardous to your health, according to a new study.

The research, led by Anneke E. K. Buffone from the University of Pennsylvania, found that when we step into the perspective of the suffering person, we can have a physiological response that could be affecting our own health negatively. But reflecting on how the pained person might feel might lead to a response that actually improves health.

“This is the first time we have physical evidence that putting yourself in someone else’s shoes is potentially harmful,” said Buffone.

The study involved more than 200 college students who were placed in the role of “helpers” to people who were suffering. Their psychophysiological responses like changes in blood pressure, heart rate, hormone stress levels and others were tracked by equipment.

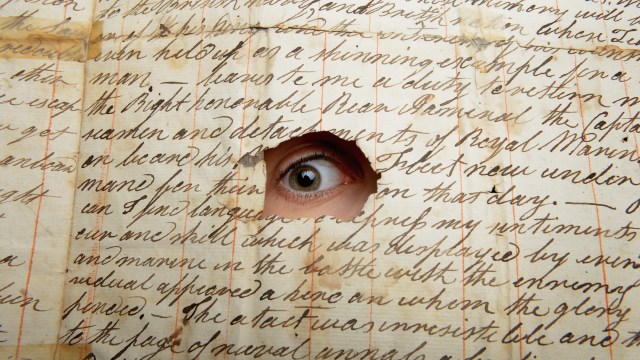

The participants had to read empathy-inducing texts which were supposedly written by their study partners. These related a tale of a person in crisis, coming from a troubled background and beset by financial difficulties related to a recent car accident while also having to take care of a younger sibling all on their own.

The subjects were asked to respond to their partners via a video message, with useful advice.

Researchers looked to evoke different types of empathy by asking questions in three variations. One group was asked how the person must be feeling, while another had to answer how they would feel in the shoes of the other person, having the same experiences. A control group was instructed to stay detached and as objective as possible.

The scientists discovered that the act of helping evoked a physiological change in the participants that differed between the groups. The group that had to imagine themselves in the suffering person’s place showed a fight-or-flight response as if they were threatened. The group that had to imagine a sufferer’s feelings, responded as if they were faced with a manageable challenge.

“A classic analogy is taking an exam,” explained Buffone. “You either feel like you’ve got it or you feel like you don’t. If you don’t, you’re going to be in that threat state; you encounter a question that throws you off, you get nervous, you get hot, you get sweaty and you can’t think. If you feel like you’ve got this, you’re calm,. Your heart may still be pounding and you may be writing fast, but you still feel confident. When we consider the situation with a little more distance, you’re feeling concern, compassion and a desire to help, but you don’t feel exactly what that other person is feeling.”

Over time, the people who respond with a fight-or-flight response risk chronic activation of the stress hormone cortisol, which could lead to health problems like cardiovascular issues. What’s important, noted Buffone, is to recognize the difference in the types of empathy – knowledge particularly significant to the welfare of professionals who confront pain and suffering daily, like those in the health industry.

Richard Davidson, a professor of psychology and psychiatry at the University of Wisconsin at Madison, who was not involved with the study, commented to the Washington Post:

“Neuroscientific research on empathy shows that if you’re empathizing with a person who is in pain, anxious or depressed, your brain will show activation of very similar circuits as the brain of the person with whom you’re empathizing,” he said.

In an interview with Big Think and in his latest book “Against Empathy”, Yale psychologist Paul Bloom argues that empathy is doing more harm than good if it gets us too close to situations that need to actions rather than feelings. He argues for compassion, rather than empathy as the more rational emotional choice when confronted with suffering.

Read the study “Don’t walk in her shoes! Different forms of perspective taking affect stress physiology” in the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology.