Do We Need Philosophy in Prisons?

It’s a well-known fact that the United States is incarcerating more people than any other country in the world – and the prison system has been widely criticized for its inhumane practices, inefficiency, and high recidivism rates.

Unsurprisingly, part of the solution lies in education. Studies have shown that inmates who take part in educational programs in prison are 47 percent less likely to reoffend.

But some say philosophy, in particular, can benefit prisoners in ways that other subjects can’t. Indeed, studies have shown that academically, children who learn philosophy in schools perform drastically better compared to their peers. But should we also bring philosophy to prisons?

Some already did. In both the U.S. and the United Kingdom, academic professors have taken up teaching in prisons. For instance, Drew Leder, professor of philosophy at Loyola College in Maryland also teaches philosophy in the Maryland Penitentiary.

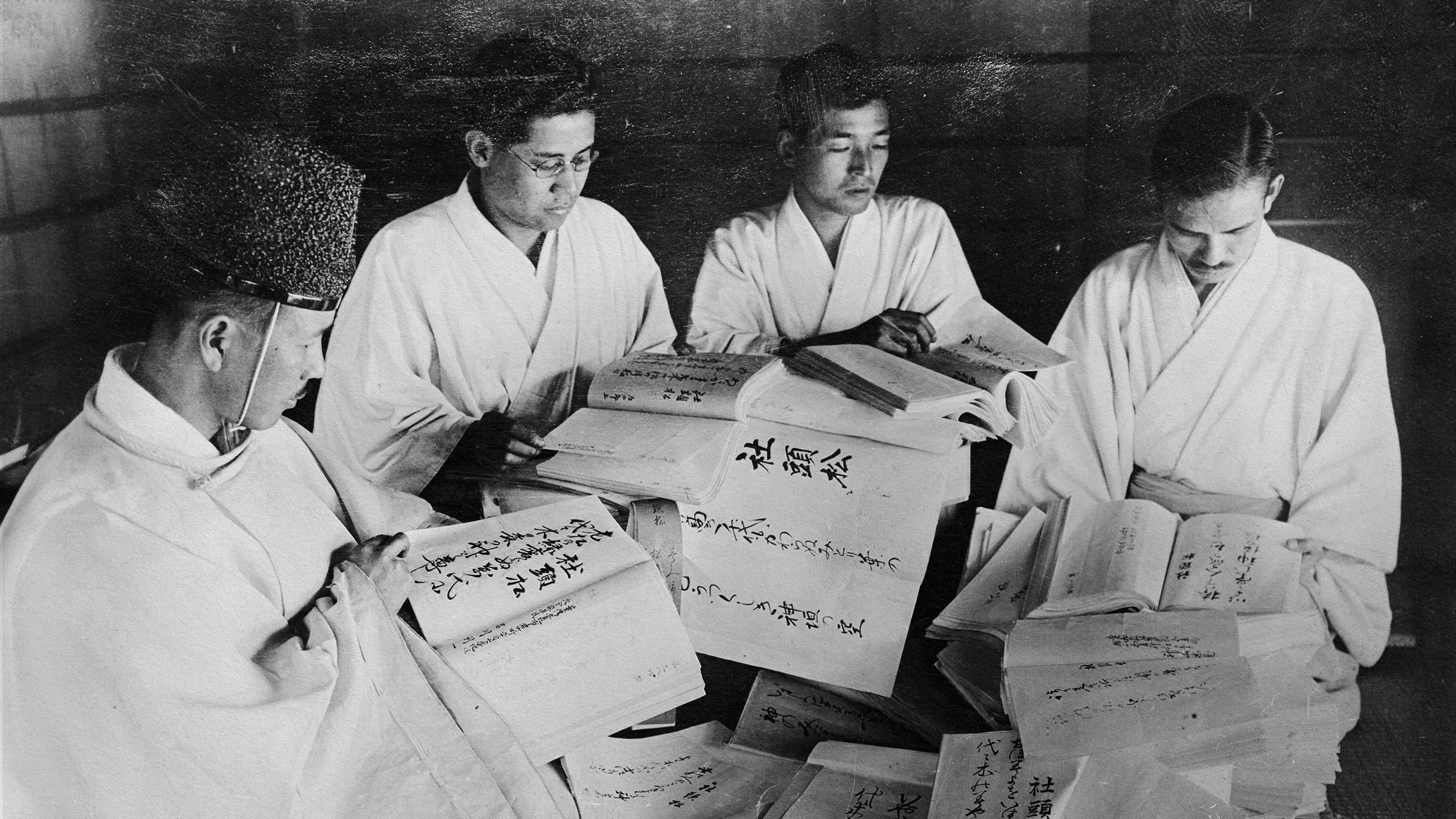

In an interview for the philosophy news website Daily Nous, Leder shares some of the questions he and his students approach in class, while turning to Epictetus or classic Chinese texts for answers:

How to build a good life as a “lifer”? How, while serving long time, to have time serve you? How, while being confined for decades on in a tiny cell, in a locked tier, in a razor-wire-fringed maximum-security prison – how to expand space and take flight?

“The men,” Leder explains, “wish to flourish, and need the resources, personal and intellectual, that will aid their quest. So they are passionately interested in our quest-ions and texts.”

In the same article, another professor chimes in: “One prisoner said that the course I taught on Foucault’s Discipline & Punishment was the most meaningful course he has ever taken.”

Does it work?

The internet is filled with first-hand accounts of what it’s like to teach philosophy in prisons, both in the U.S. and the U.K. But does teaching philosophy in prisons actually help the prisoners?

In the United Kingdom, the University of Edinburgh has carried out research aiming to assess the impact of teaching philosophy in prisons and reported that a seven-week course in philosophy simultaneously raised the inmates’ levels of self-esteem as well as their ability to listen to other people.

Additionally, the course reportedly improved the prisoners’ critical thinking skills – i.e. the ability to give reasons for their beliefs, as well as the ability to understand other people’s arguments.

In another study, published in the Prison Service Journal, Kirstine Szifris documented the results of a 12-week philosophy course in a grade B prison in England. The research – consisting mainly of interviews – abounds with students’ testimonials, showing that philosophy enabled them to consider new perspectives, change their mind, and broaden their intellectual horizons.

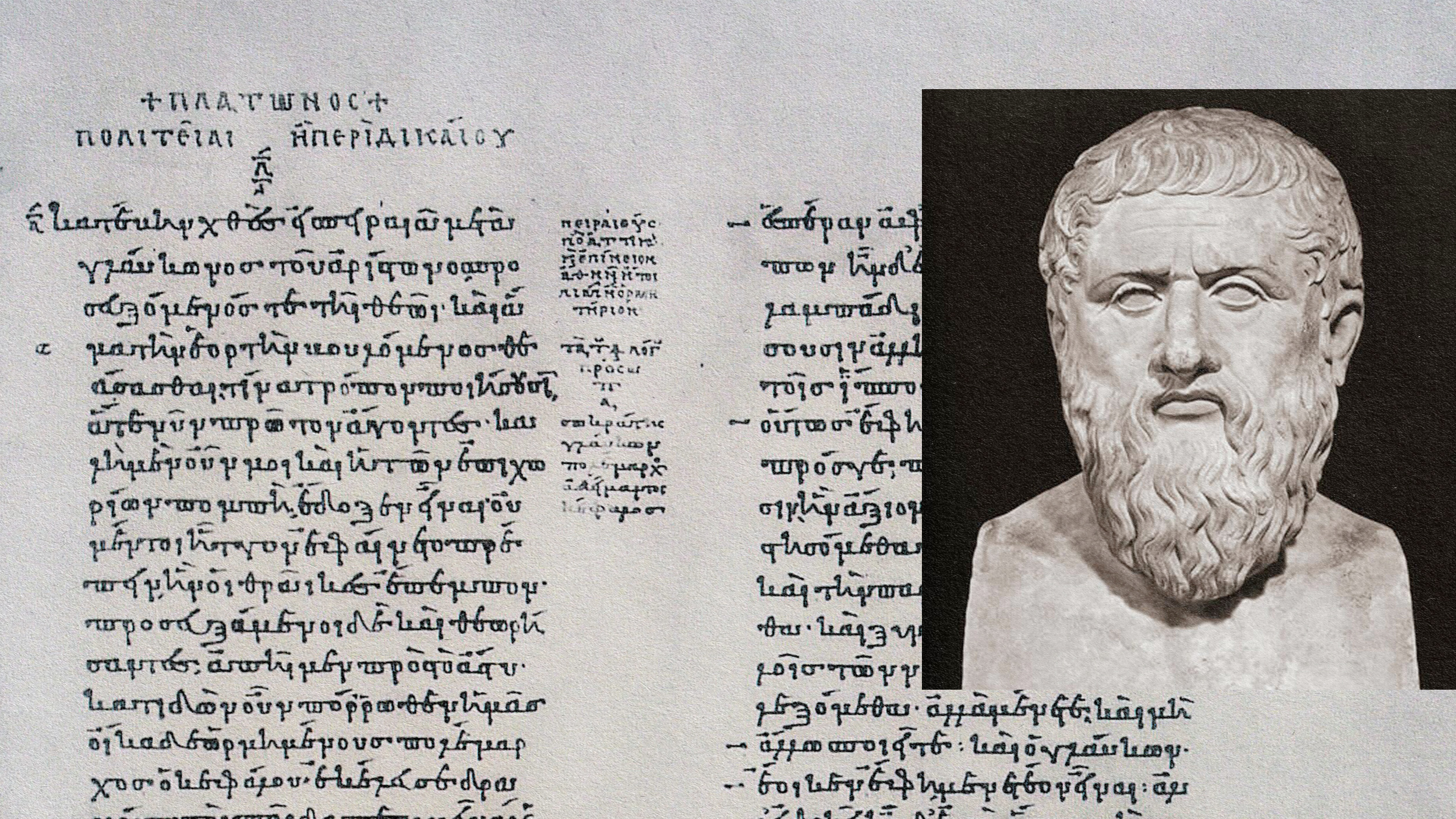

“The Death of Socrates” (1787), by Jacques-Louis David. Public Domain. The Greek philosopher Socrates (469 – 399 BC) is forced to commit suicide in prison by drinking hemlock, surrounded by his friends and followers, 399 BC.

Even more interestingly, the study sheds light on some distinct advantages that philosophy, in particular, can offer its participants.

Philosophy vs. therapy

HMP Grendon – the prison where the study was carried out – is already a forward-thinking facility that focuses primarily on rehabilition through group therapy.

But Szifris’ research shows how philosophy courses differ from therapy. While the latter focuses on the personal, the former centers on the abstract – and this may allow the participants to distance themselves from their own situation and past in ways that therapy does not.

The focus of therapy is to annihilate the participants’ criminal tendencies, so the prisoners approach therapy as “offenders.” But in philosophy classes, they approach the philosophical issues as people. Although the author advocates for philosophy as complementary to therapy, she also notes the “subtle distinctions” between therapy and philosophy:

“[In] therapy, the fact that participants are in prison underpins the dialogue (…) there is an underlying understanding that the aim of therapy is to reduce criminal tendencies. (…) In philosophy, participants enter the dialogue as people, members of society ready and willing to discuss what that means to them. By starting from this different perspective, participants are able to reflect on themselves as ‘whole’ persons without needing to reflect directly or exclusively on their offending behavior. “

Furthermore, the study points out, philosophy may help the prisoners create a new identity for themselves. Existing research emphasizes how important it is for inmates to leave behind their criminal past and reinvent themselves.

Philosophy classes may allow the participants to distance themselves from their personal circumstances and view their actions in the broader context of “society” and “morality.” This much-needed distance provided by philosophical dialogue may, in the long run, help the prisoners avoid recidivism.