3 Keys For Cultivating Genius

There has never been an easy way to define genius. Intelligence scores are sometimes used, though numbers fall flat when in many artistic domains. A Mensa-level mathematician might be a genius, but what of an acclaimed composer who dropped out of high school? Genius has always been a relative and subjective term.

Psychology professor Dean Keith Simonton contemplates two varying views of genius: one of achieved eminence, the other as exceptional intelligence. His research points strongly toward the first: genius as a skill that can be cultivated with discipline.

Simonton distinguishes between two popular definitions of genius. He points to Kant with the first, which is also the focus of his article: exceptional achievement. He cites Beethoven, Shakespeare, and Tolstoy as examples of those who have produced lasting art. This is different than the type of genius measured on intelligence tests. As he notes, many people with high IQs “do not produce original and exemplary accomplishments.”

Heredity has long been an argument for genius: you either have it or don’t. While certain genetic circumstances set you up for success—runners with more fast-twitch muscle fibers tend to be sprinters, for example, while those with more slow-twitch fibers are better suited for distance—there is no predetermined roadmap to genius. Simonton does find two recurrences among geniuses throughout time, however.

First, they don’t put in as much time in one domain as their less creative counterparts. At some point a number of ideas collide and point to a new trajectory; their genius fits together the pieces. Simonton believes this can be challenging if you’ve spent your entire life focused on one domain of study.

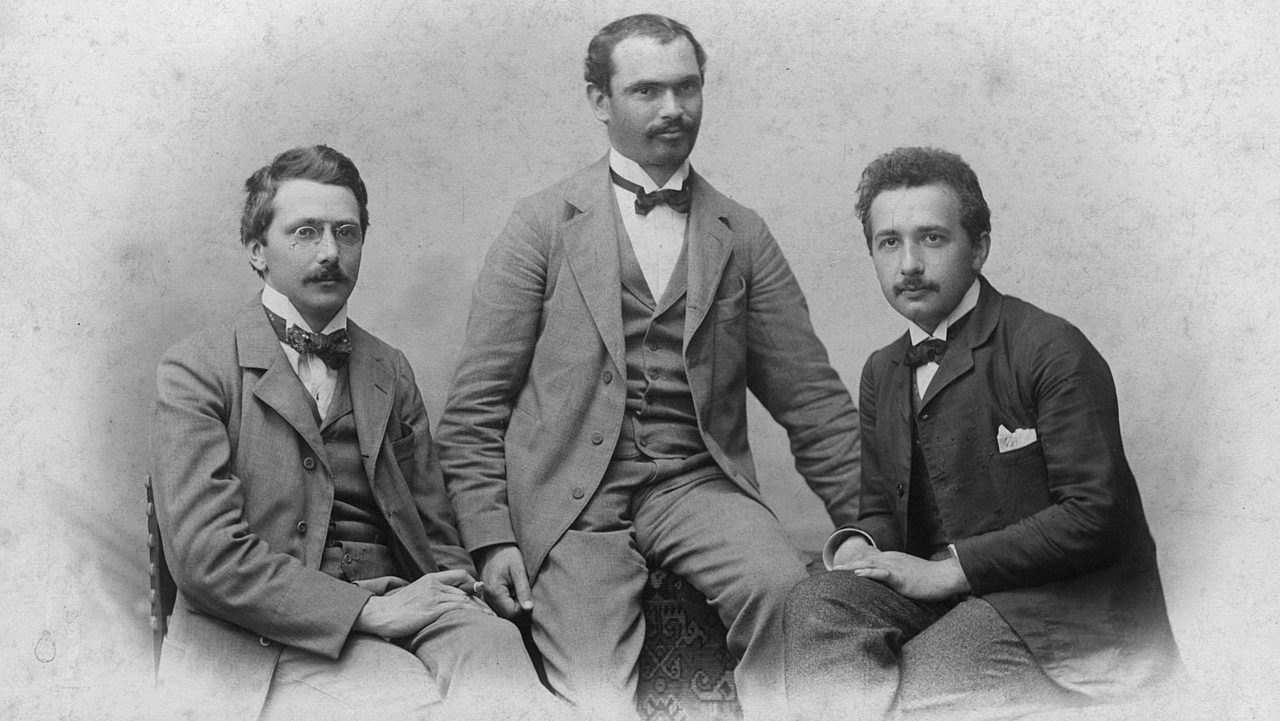

This blends with the second, that geniuses “display exceptional versatility.” They are not limited to only one area of knowledge. Einstein enjoyed playing Mozart and Bach on the violin; he even had revelations about physics during his performances. Such a person, Simonton writes, is open to new experiences. Cognitive and behavioral flexibility along with “tolerance of ambiguity and change” sets them up to thrive.

Motivation matters when cultivating genius, writes science journalist Daisy Yuhas. She writes that psychologists have identified three critical elements for attaining such achievements.

Autonomy

Research shows that people who are given a choice to decide what field to pursue, rather than being told what to do or coerced into a decision, are more likely to excel in their occupation. If you are forced into your vocation you’re less likely to have the passion necessary to chase excellence. “Pursuing a task you endorse is energizing,” Yuhas concludes.

Value

Yuhas continues: “Motivation also blossoms the you stay true to your beliefs and values.” Researchers from the University of Maryland and University of Arkansas discovered students who value their research are more willing to investigate the topic independently. Another study at the University of Virginia found that students who write about science as it relates to their own lives are more thorough and detailed than those who simply summarize the lessons. Owning the subject matter personally makes a profound difference.

Competence

Practice makes genius, so the adage goes. Yuhas cites the work of Stanford psychologist Carol Dweck, noting that “competence comes from recognizing the basis of accomplishment.” Dweck’s studies on innate talent versus hard work are well documented. Students told that they’re geniuses are less likely to push their boundaries if they fare well on a test, while students believing they can do better with hard work are more likely to accept the challenge.

Few of us will ever soar like Michael Jordan, but even he knew discipline and hard work pay off. After dominating the NBA he briefly left to try his hand at baseball. In his first season back on the court the Bulls faltered; he had been coasting on previous successes. The off-season proved to be a wake-up call. He tied up his Air Jordans and went to work. His second three-peat only came when his competence was restored—an inspiring tale for everyone trying to shine.

—

Derek’s next book, Whole Motion: Training Your Brain and Body For Optimal Health, will be published on 7/4/17 by Carrel/Skyhorse Publishing. He is based in Los Angeles. Stay in touch on Facebook and Twitter.