Venus flytrap jaws create tiny magnetic fields when they snap shut

Credit: Jeffery Wong/Unsplash

- Venus flytrap leaves shut in response to physical touch, salt water, or thermal stimuli.

- A team of scientists from Berlin have captured the magnetic charge that accompanies the closing of the plant’s trap.

- Incredibly sensitive, non-invasive atomic magnetometers picked up the elusive signal.

For many children, the revelation that there’s such a thing as a Venus Flytrap, Dionaea muscipula, is an amazing moment. The choppers of the sneaky plant predators are like something out of a fairy tale gone wrong. Adults can’t help but be fascinated by them too, and now scientists at Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (JSU) and the Helmholtz Institute Mainz in Germany have discovered something new that’s surprising about these little demons: Every time they entrap prey, they give off a measurable magnetic charge.

“We have been able to demonstrate that action potentials in a multicellular plant system produce measurable magnetic fields, something that had never been confirmed before,” says lead author Anne Fabricant.

The plants’ bivalved snap trap (left), side view of a destained trap lobe (right)Credit: Fabricant, et al./Scientific Reports

According to Fabricant, the finding isn’t that much of a shock: “Wherever there is electrical activity, there should also be magnetic activity,” she tells Live Science. And it is electrical activity in the form of action potentials that trigger its maw—really a pair of leaf lobes—to close when a hapless bug lands inside them, attracted by the nectar with which the plants bait their trap.

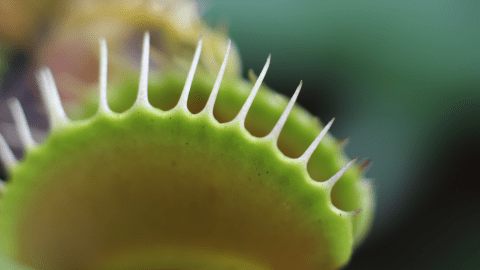

Along the inner surfaces of the lobes are trichomes, hair-like projections that cause the trap to close when they’re disturbed by prey. One touch of a trichome is unlikely to cause the trap to shut — perhaps a mechanism that helps the plant avoid wasting energy on false alarms. A couple of touches, though, and it’s chow time. The lobes come together as the bristles at their edges intertwine to help contain the prey. As the traps compress the trapped insect, its own secretions such as uric acid cause the trap to shut even more tightly, and then digestion begins.

In any event, just because the JSU researchers had reason to suspect the plant would give off a magnetic charge, catching it doing so was not a simple task.

Average action potential and corresponding magnetic signalsCredit: Fabricant, et al./Scientific Reports

“The problem,” says Fabricant, “is that the magnetic signals in plants are very weak, which explains why it was extremely difficult to measure them with the help of older technologies.” Still, where there’s a will: “You could say the investigation is a little like performing an MRI scan in humans.”

It’s not just trichome flicks that trigger the trap — it will also close if triggered by salt-water, or with an application of either hot or cold thermal energy. The researchers applied heat via a purpose-built Peltier device that wouldn’t introduce any background magnetic noise to mask or overwhelm the faint magnetic signal they were seeking. For the same reason, the experiments were conducted in a magnetically shielded room at Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt (PTB) in Berlin.

The researchers used atomic magnetometers to measure the planets magnetic charges. The atomic magnetometer is a glass cell containing a vapor of rubidium atoms. When the traps were triggered, the magnetic charges released changed the spins of the atoms’ electrons.

The researchers picked up magnetic signals at an amplitude of up to 0.5 picoteslas. “The signal magnitude recorded is similar to what is observed during surface measurements of nerve impulses in animals,” says Fabricant. It’s over a million times weaker than the Earth’s own magnetic field.

Other researchers have detected magnetic charges coming the firing of animal nerves — including within our own brain. The phenomenon is referred to as “biomagnetism.” Since other plants have action potentials, they may also generate biomagnetism, though less research has been done on them.

It’s to other plants that the attention of the JSU team now turns, as they go looking for even smaller magnetic charges from other species. In addition to providing new understanding of nature’s use of electricity, non-invasive detection technologies such as the one employed by the group could one day be utilized for more insightful monitoring of crops as they respond to thermal, pest, and chemical influences.