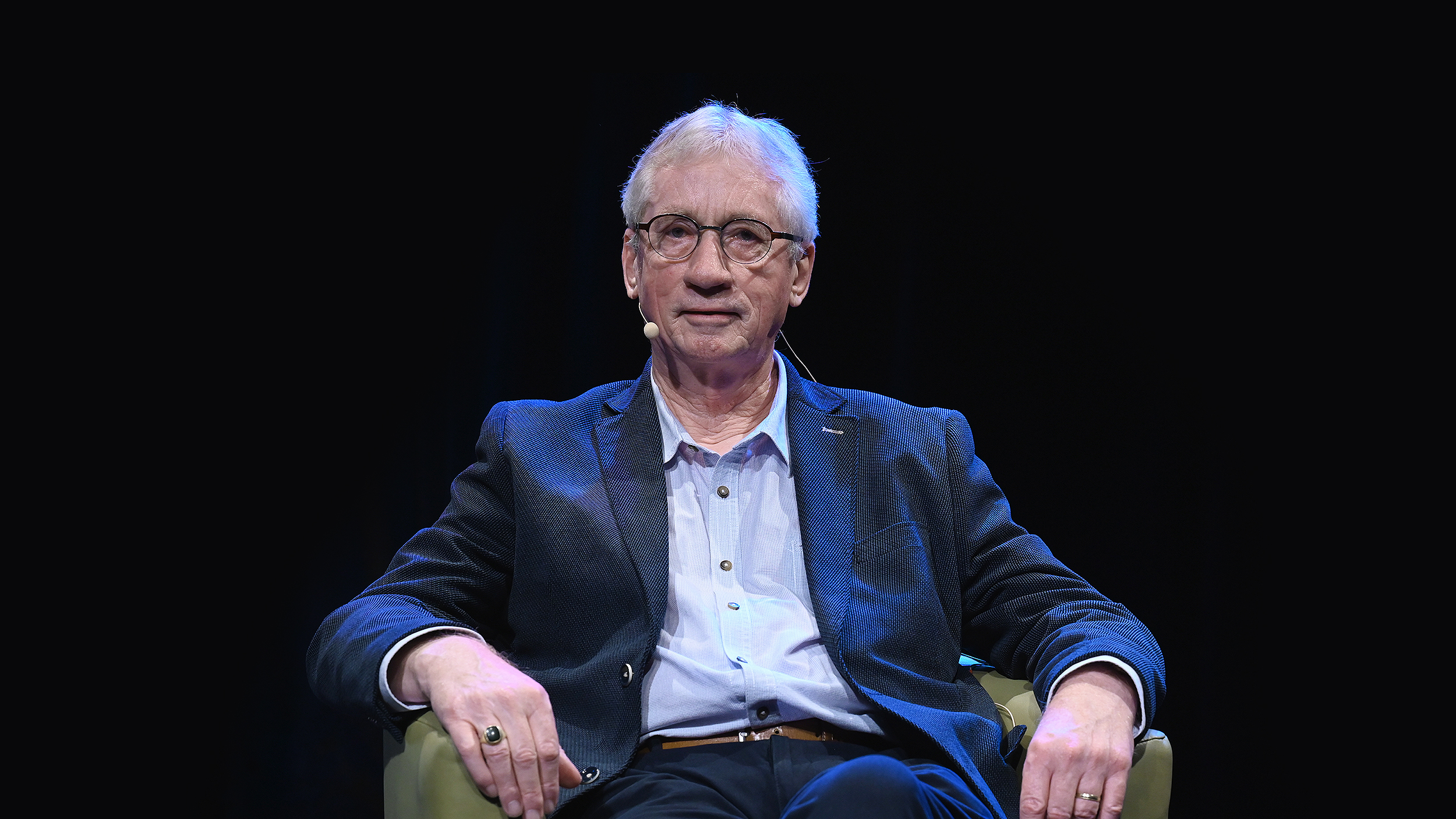

Barbara J. King has grown accustomed to hearing “the A word.”

One of the world’s top experts on animal cognition and emotions, the former college prof—she taught biological anthropology for 28 years at William and Mary—is sometimes accused of overreacting to certain animal behaviors by calling them feelings.

In other words, critics say she’s guilty of anthropomorphism. She just calls it “the A word.”

Her best-known book is the critically praised How Animals Grieve (2013), but these days she’s taking the conversation beyond animal emotions and into more socially-conscious territory. The title of her 2017 book, Personalities on the Plate: The Lives and Minds of Animals We Eat, almost says it all.

Her next book, due in 2021, will address how we can take our compassion for animals a step further not just for the sake of the creatures themselves, but for the planet as a whole.

ORBITER recently caught up with King to talk about animals, their emotions, and the urgency of the climate crisis. And, of course, “the A word.”

ORBITER: Were you into science as a kid?

Barbara J. King: Oh, yes. One of my earliest memories is turning my parents’ vacuum cleaner into what I imagined to be blood transfusion machine because I wanted to be a doctor. I always wanted to be in the medical profession, all the way through elementary school, high school, and college.

Did you grow up with animals?

Yes, always. We always had cats in our home and, at one point, a dog as well, and I was fascinated by both. One of our cats actually took walks with us, and that taught me at a very young age something about personality. I wouldn’t have put it in those terms, but something about animals being different. They’re as different as we are. My cats were as different one from the other as my friends were, and that was a really important lesson early on.

What led you to make a career out of researching animal emotions?

When I stumbled into a biological anthropology class, I discovered an opportunity to connect my love of animals with scholarship in anthropology, and I really never looked back. I moved on from my failed medical hopes, and I just lit up when I started to observe monkeys as an undergraduate. In graduate school, I applied to go into the field to study apes, and I was hooked. I had interactions with Birute Galdikas and Dian Fossey, who were two of the three Trimates (along with Jane Goodall).

I didn’t end up going to either of their field sites, but I did end up going to Kenya to study baboons. And the more I observed, I realized I was seeing a dynamic system—a social group of animals incredibly attuned to each other and exhibiting embodied communication. We all communicate with our gestures or body posture, as well as our voices, but we don’t always fully realize the degree to which this kind of communication is happening. I really saw that with baboons in Kenya and later with apes in captivity.

I started to consider questions of what they were thinking and feeling. It’s such an exciting time to do this, because there’s been this whole renaissance of people doing this work—from Jane Goodall to Frans de Waal to so many others. So there was a way for me to plug into a framework and learn from people who were further along than I was.

Some of your critics say you over-anthropomorphize when it comes to animals and emotions. What do you say to those critics?

When I talk about the “A word,” as I call it, I start with the definition—which is the inappropriate ascribing of human qualities or emotions onto other species. And clearly we have to be careful.

If someone says, “I was playing with my dog, and my second dog came up and looked at me and gave me this baleful glance, so clearly that dog was jealous”—that’s clearly a projection of what we feel in the absence of any real evidence that the dog is feeling that way. We don’t want to do that.

I work mostly on animal grief, and we have credible evidence to suggest that animals express this particular emotion. So if we start with a good definition—which I have done with animal grief—and we see behavior that lines up with that, it’s quite scientific to say there’s a good chance that there’s animal grief here. We have to always consider alternative hypotheses, but there’s as much risk in denying what we think we’re seeing as there is in rushing to embrace it.

I’ve spent the last seven years of my career expressing this definition in my book, my articles for Scientific American, my public speaking, and everything else, working along with other scientists and observers. Yes, it can be hard to know, and we’re going to get it wrong sometimes. But to reject that whole project because of worries about anthropomorphism is wrong.

Where do we draw the line? With mammals? Birds? Reptiles? One could go all the way down to single-celled organisms. Does every living thing experience emotions?

That’s a huge question. I think we know from ornithologists, Bernd Heinrich and others, that some animals behave in ways that indicate they’re expressing grief. Canada geese and magpies are very good examples of survivors acting around a dead body in very particular ways that seem to indicate emotion. I don’t expect ever to find that fish, spiders, etc., experience grief. I could be wrong, but I don’t expect that. I think we just have to look and ask the question.

Neuroscientists make this distinction between emotion as a body state and a conscious-aware state, but I’m not really on board with that definition for lots of complicated reasons. But I think it does clue us in to something important: We have to understand what an animal is capable of experiencing consciously. And the credible evidence that I have found ranges from what you might call the usual suspects of cetaceans, elephants, chimpanzees, and monkeys—the big brain mammals—to include birds, farm animals, and companion animals. We know that dairy cows experience not just stress, but what looks to me like grief when they’re separated repeatedly from their offspring.

Then what makes humans unique from animals when it comes to emotions?

I think we’re unique because we tell stories; we live through narration of the past, present, and future. That’s part of the answer involving emotions: We have a spectacular fine tuning of our emotions, so we have not only happiness, joy, sadness, grief, fear, and anger, but so many more—hope and jealousy and envy and profound PTSD. But I think the main distinction between humans and animals is that in most cases it’s quantitative rather than qualitative.

We have found PTSD in elephants—good, credible science. We know that chimpanzees, when kept in captivity, can show profound depression, and we wonder if they feel hope. How do you recognize hope in an animal? We know that they have the flip side of that, which is despair. All to say, yes, we’re unique, but it’s very much on a continuum.

I’m looking at my dog right now, whom we rescued from a shelter a couple years ago. It seemed he had anxiety, and possibly came from an abusive situation. I don’t think I’m anthropomorphizing . . .

Oh, exactly! I live with rescued cats here in my home. I’m on the board of the Oklahoma Primate Sanctuary, and some of the monkeys clearly had difficult backgrounds either in the pet trade or in research. We just see over and over that these things are real. So when I say that we humans have a greater profundity and range of emotions, I want to be cautious about that. Because we’re only really beginning to understand the depth and profundity of animal emotional experiences.

What are you working on these days?

I’m working on my seventh book, and in it I’m saying, “Okay, we as a society have taken a tremendous leap in understanding animal cognition and emotions, so now what? How do we act for animals in order to help them? And, while doing so, help ourselves and help the planet?”

One, we’re recognizing, given that farm animals are thoughtful and that they feel, that eating meat and dairy causes a great deal of animal suffering. And two, we’re realizing that eating meat and dairy and eggs is a huge part of the reason why we’re in a planetary crisis with global warming and climate change. The science is there. I’m writing about peer-reviewed articles, showing how much animal agriculture contributes to global warming. It’s enormous.

People are always asking me, “What can I do?” Given this planetary crisis, for many of us—not all of us—the most immediate and effective way to make this change is to eat less or no meat, dairy, and eggs. I am absolutely impassioned by this because I don’t think we have a lot of time to screw around with what’s happening. So my role models are vegan activists, but at the same time, I’m not suggesting that everyone has to become vegan. Do you know about the reducetarian movement?

No, what’s that?

Reducetarian is a word coined by a man named Brian Kateman, who founded the movement. I attended their first conference in 2017, and I’m attending the next one in DC later this month. It’s an umbrella term that brings together everyone who’s interested in this idea of reducing meat, dairy, and eggs. So you could be vegan, vegetarian, a flexetarian—it encompasses all of this. Which gets to my message these days: How do you meet people where they are and talk to them about what we eat without pissing them off?

It’s hard. I give talks all around the country. I go to Oklahoma, which is cattle country. I go to Memphis, which is barbecue country. And I’m trying to talk to people about this, and as an anthropologist, I realize that there are cultural, social, family traditions going on here in terms of what we eat. But at the same time, while I don’t think the requirement is for everyone to go vegan, I think we should listen to people who are telling us that the science shows if we can reduce animal agriculture and fossil fuel emissions, we can make a big contribution into what we need to do.

It’s very aspirational. I want to be very humble about this. I don’t eat a perfect diet by any means. I’m not fully vegan, although I’m close. I want to talk to people and say, “Look, we’re all in this together.”

A lot of the push back comes when people say, “Not everybody can afford this. Not everybody has the resources. Not everyone has the access.” And that’s true. So I’m talking to people who have the resources to make choices, and this is the contribution that we can make.

I know cattle emissions contribute to global warming. So if a person doesn’t eat much beef, but eats mostly chicken and fish, that’s pretty good, right? Asking for a friend.

Here’s where I don’t want to lay on the guilt, but just have discourse. This is exactly the situation that I’m interested in, because I could give you two different answers. One is to tell you that chickens suffer horribly, that the number of chickens who aren’t stunned properly and who end up going in the scalding boiled water is really high. So we don’t want to just dismiss the fact that they’re suffering. But the type of science that I’m reading is talking about how meat and dairy production eats up 83 percent of the world’s farmland and produces 56 percent of agriculture’s greenhouse gas emissions.

This is overwhelmingly because of the amount that we’re eating. No one is suggesting that these are going to go down to 0, but it’s all of a piece. A lot of people have concluded that not eating beef could make a major contribution, but the question, if I may, is why shift to chickens? Why not shift to some of the amazing plant-based products that we know don’t cause animal suffering and don’t contribute to this problem? This is the best time in the whole world to be reducetarian.

My refrigerator is full not only of the things you would expect—fresh fruits and vegetables. But now we have things like Beyond Burger, Impossible Burger, and nondairy milk, ice cream, butter, and yogurt. All of these things are available to us.

When you consider whether there’s such a thing as humane slaughter in the first place—which I doubt—it certainly doesn’t exist on factory farm slaughterhouses. That’s prong one of the argument. Prong two is the planetary crisis. I ask people, “What is good about this picture of eating a lot of meat and dairy and eggs, when we know these things are going on, and when many of us have alternatives?”

How does dairy—the act of milking cows—add to the suffering of animals?

That took me a long time to understand, but I’ve researched it. Dairy cows are kept more or less continuously pregnant because if you want milk, you have to have lactating females. On a farm, their offspring are continuously taken away from them days after birth. And there’s really credible evidence to show the mothers are grieving; it’s very hard on them. Then what happens is that male calves are dispatched immediately, mostly for veal. And the daughters are raised so they can then lactate and give all this milk. All of that’s very hard on the bodies of the females. And then the “spent” dairy cow goes to auction, and that auction is for meat; I’ve learned that the dairy and the meat industries are incredibly entwined.

So what would you say to someone who says, “Thanks for the info. I’m not ready to go vegan, but what’s one thing I can do?”

I think the best thing is to just reduce, reduce, reduce across the board. I really do believe people who are making an effort to find plant-based products are contributing in a very positive way right now. It’s not necessary to be 100 percent pure about it. But if you’re contributing to consuming less meat and dairy, that’s a good start.

Many people of faith, particularly Christians, believe the Bible says that God gave us plants and animalsto eat, that we should therefore feel free to do so. What would you say to them?

The people I know in the religious community, who I have joined with, have a different point of view. They say it’s not about dominion over animals, but rather community with other animals on the earth. I resonate with, and it seems to be in line with the compassion that underlies that religious tradition.

The religious argument is one argument for eating meat. Another is that it’s natural, because all animals eat meat, and we evolved that way. In short, my answer is that yes, we did evolve, millions of years ago, eating meat. But evolution also made us capable of empathy, flexibility, and adaptation, so now is the time to use those things, and to see where we are in the world and to think reflectively about this and to change what we’re doing—for the good of all of us.

Tell me a little more about the book you’re now writing.

We’re aiming for 2021, so it’s still pretty far off. But I want this book to be just another part of my big kaleidoscopic project to talk to people about our love for animals—and how we can translate that into sympathetic action for animals. Again, I don’t go around telling everyone they have to be vegan. That’s not a helpful approach. Similarly, I don’t go around telling people we need to dismantle all zoos, or that you should never take your family to a zoo again. But I’m writing about how we can go to a zoo and keep our eyes and ears open, to be able to express concerns and take action when necessary. These issues are complicated, and I’m trying to strike a tone of openness, an aspirational tone for how all of us, including me, can do better for animals without shutting down conversation with people who feel differently.

This is very important to me. There is a stereotype of the angry vegan, but I don’t think the stereotype is often true. So many vegans I have learned from also take this aspirational approach of, if we’re going to have compassion for animals, we need to have compassion for each other.

Watch King’s recent TED talk, “Grief and love in the animal kingdom”: