They Still Don’t Get It, Do They? Why Women are Still Underpaid and Undervalued at Work

In 1995, I published They Don’t Get It, Do They? Closing the Communication Gap Between Women and Men after writing “The Memo Every Woman Keeps in Her Desk” — a Harvard Business Review reprint bestseller. In both cases, the purpose was to explore the role everyday communication plays in advancing or slowing the progress of women at work.

Certainly women realize more than they did then that stretching communication styles and adapting to our surroundings are important to career success. But as keen observers of workplace issues point out, the last two decades have not produced the results expected. In fact, there has been a palpable stall in women’s progress on many fronts, especially in value of work and senior-level promotions.

Women are exiting high-tech jobs even as programs are promoting their entrance into those fields. Among fund managers, where the presence of women increases organizational success, women are also moving on.

By invitation from Big Think, below are excerpts from They Don’t Get It, Do They? with explanations regarding why significant problems moving to senior levels still exist for women at work and what can be done to change that.

At the heart of the problems women face is the fact that men and women working together do not speak the same language. … Fundamental differences in the way women and men think as described by Carol Gilligan in her book A Different Voice lead to fundamental differences in the way they communicate job commitment, managerial expertise, leadership, and a host of other promotion-relevant competencies. … We worry about saying that men and women differ. But they do, if not innately, then because of socialization; and the way they communicate these experiences is therefore different as well.

Unfortunately, as Gilligan also wrote, it is difficult to say “different” without saying “better” or “worse.” Men have largely developed the standard measurements of workplace value. When women’s styles do not conform, the natural conclusion is that there is something wrong with women and that they cannot effectively lead.

Most women prefer to believe that men welcome them to the workforce. In fact, when young, in their “cute-and-little phase,” men are often willing to mentor and guide them. So young women naturally wonder, “Why all the fuss?” After all, things appear to be going quite well. That’s where women lose a lot of valuable learning time. When they become candidates for promotions previously taken by men, they’re unprepared for the precipitous decline in collegial support. As UCLA Distinguished Professor of Psychology Shelley Taylor shared with me, “The whole process of learning that men aren’t all that comfortable with women at senior levels is very painful for women.”

One option for women was to become more like men. When that didn’t work, women became entrepreneurs or tried to beat men at their own game. They were given labels that were uncomfortable. Some ignored or rejected them and pushed on. Doing so well means altering how you respond to put-downs and constraining categories — changing your communication style so that people think twice about trying to put you in what they consider your place.

“Communication is a complex activity. … When it comes to the big stakes game of senior management, women’s communication strategies must be both sophisticated and variable — less focused on what men want, more focused on what works both professionally and personally.”

Communication patterns between women and men have not adequately adjusted to the increasing presence of women in the workplace. Changing this condition means stepping out of the scripts we’re used to enacting, especially the dysfunctional ones. Being left out of meetings, given dead-end tasks, enduring far more interruptions, and having ideas ignored only to be adopted later as belonging to someone else are just a few of the problems women still find infuriating. The reason why these kinds of problems continue to exist is, in good part, fear of coming on too strong.

“The truth is that a wide range of communication strategies exists between demure and abrasive. Clinging to either end of the range is a recipe for failure. Many women worry that assertive behavior will upset men and lead to disfavor. What they have failed to consider is that they aren’t exactly in favor anyway. Letting others label your interactions, and exclude, interrupt, and devalue you is not better than upsetting a few men now and then.”

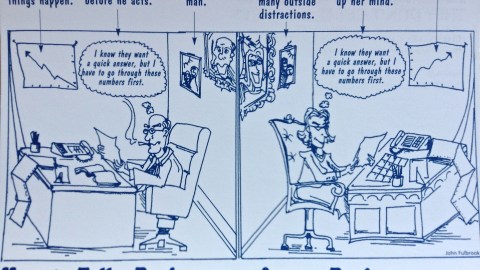

To change the overall picture for women in the workplace, it’s critical to change the day-to-day as well. That means taking a good look at how we communicate. The conversation below shows how easy it is to slip into a dysfunctional communication pattern (DCP):

Michael: You sure came on strong in that meeting.

Jessica: I was just trying to make a point.

Michael: Well, you certainly did that.

Jessica: Do you think I overdid it?

Michael: It’s not what I think that counts.

Jessica: Did Al say anything about it?

Michael: He didn’t have to. Did you see his eyes?

Jessica has abdicated control in this conversation. Each of us is at least 75% responsible for what goes on in interactions. If Jessica responds regularly this way, she is allowing other people to limit her communication and to silence her at meetings. Instead, she could change the course of the conversation.

Michael: You sure came on strong in that meeting.

Jessica: Someone had to. It’s an important project.

This reply is short and unexpected. It can be said calmly and/or directly. It conveys that Jessica is confident and that she has a persuasive, legitimate, work-related reason for her actions. She refused to participate in a script and implied label of “pushy” that lowers the value of her contributions. An added advantage: Michael is less likely to slip into that script again.

To the extent that women, in particular, recognize dysfunctional scripts and take steps to intercept them before they do damage, the way they’re perceived at work can become increasingly positive. Work is about getting jobs done. It’s not home. How we’re perceived is shaped by daily conversations. To the extent that women manage them, the likelihood of progress to senior levels is enhanced.

Fear of being labeled is still a significant obstacle for women. The truth is — you’re going to get labeled anyway, so you might as well have some input.

They Don’t Get It, Do They? was released this week on Kindle here. Kathleen also blogs on communication and politics here.

Photo: Cartoon by John Fullbrook for Little,Brown publisher