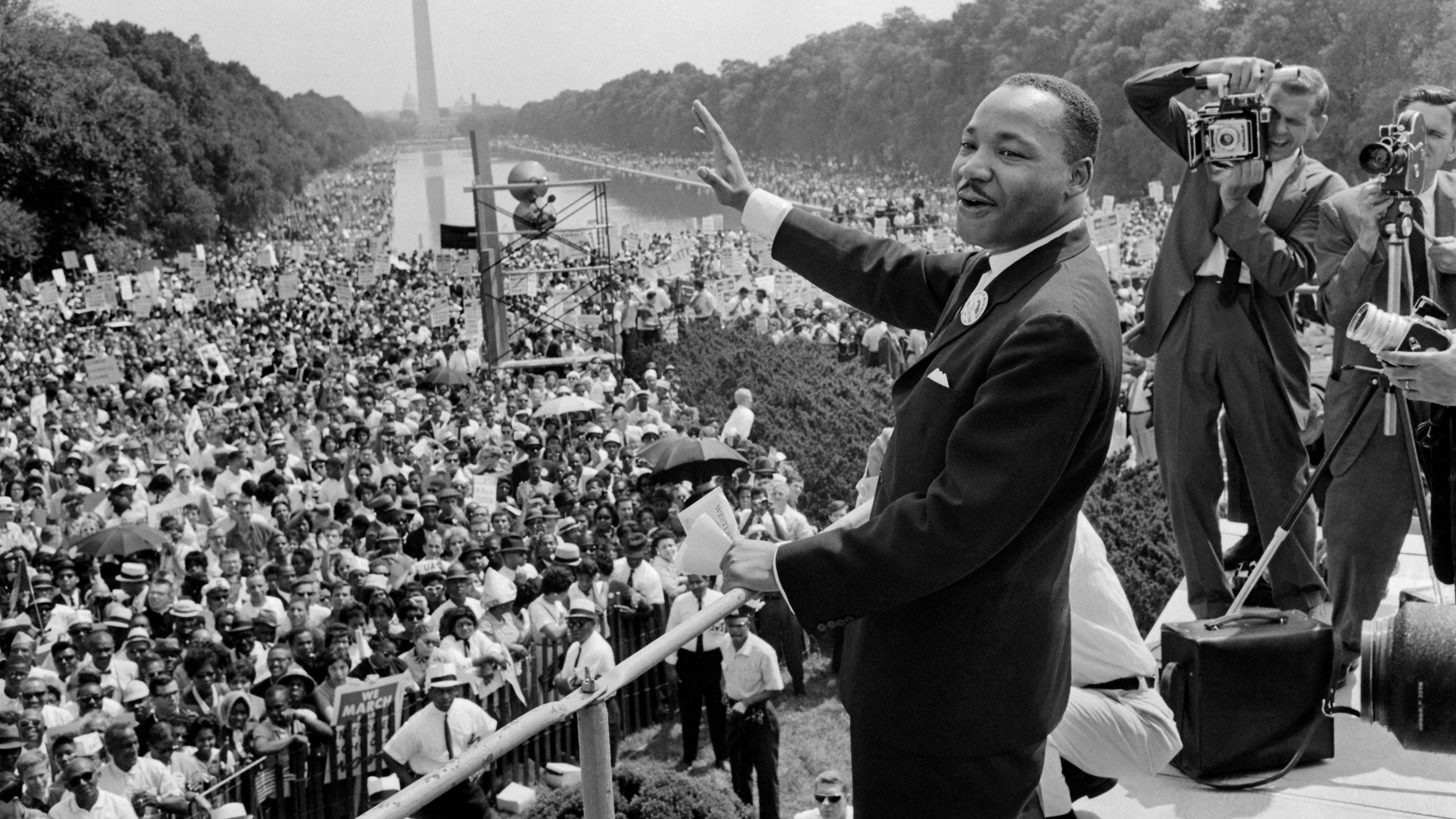

How Hope Works in the Black Community, from Martin Luther King Jr. to Obama

Hope is an important tool in life. It motivates us to look past everyday challenges toward specific goals, however difficult they may be to achieve.

In the African-American community, hope has always had a more particular connotation. As Andre C. Willis, Assistant Professor of Religious Studies at Brown University, has said, hope among African-Americans is born of “centuries of despair and dehumanization” as well as the “tragic sense of life” given us by the Protestant tradition.

Universal to the feeling of hope—that belief in the possibility of positive outcomes—is how it works in the brain. As a cognitive process, hope makes it possible for us to be proactive about the specific plans we hope to achieve, and pursue them with “agency” and “pathways, according to psychologist Rick Snyder. Hope is what allows us to act with intention in the face of obstacles.

While hope may start in the brain, it reaches beyond the self and bonds individuals who share common goals against common obstacles. Progressive societies have relied on hope in the face of conservative opposition, from the Civil Rights Movement to the presidential slogans of Barack Obama. Researchers recognize different kinds of hope, however, and not all hope is equally effective.

In his research, Dr. Willis draws a distinction between the hope envisioned by Martin Luther King, Jr. and President Obama. While Dr. King’s oratory is often boiled down to his “I Have a Dream” speech, he also gave an “Unfulfilled Dreams” speech which viewed hope as treacherous.

Willis sees King’s version of hope as having Protestant roots, based on the knowledge that its work will never be completed. King’s vision, according to Willis, was like a “way of relating to suffering” that allows you to keep going forward and do meaningful work.

So how did Obama fare by comparison? In Willis’s view, outlined in his 2017 paper, “Obama’s Racial Legacy,” President Obama’s impact has been to deepen racism that masquerades as color-blindness. As a result, grassroots groups like “Black Lives Matter” have struggled to gain enough traction to challenge the status quo.

Instead of advocating for a post-racial society as Dr. King did, Obama’s vision of hope moved the African-American community from disappointment toward social goals perceived as “realizable”. In Obama’s America, rationally achievable goals took the place of dreams.

“Hope” poster by Shepard Fairey. 2008.

In a series of interviews with African-Americans regarding Obama’s legacy, the LA Times drew an important distinction: attitudes toward Obama-the-individual were generally positive, while doubt lingered on whether his Presidency produced the change needed. Black lives had improved with respect to education, healthcare and criminal justice reform, but still suffered from a lackluster economic recovery. Unemployment among African-Americans remains nearly twice that of whites.

According to David Golland, an associate professor at Governor’s State University, there has been little statistical improvement in African-American life in areas of child mortality, educational attainment, or teenage crime and drug use.

On the other hand, Golland thinks that a value of the Obama Presidency may lie in its symbolic nature:

“Getting away from the word metrics, there’s just something about a generation of children growing up and seeing someone who looks like them in the White House that cannot be underestimated,” said Golland.

Offering a more probing historical perspective, a 2016 article by Chernoh Sesay Jr., Associate Professor of Religious Studies at DePaul University, looked at hope as an integral part of the black slave experience. In the immediate wake of the Revolutionary War, for example, black petitioners filed a number lawsuits in Massachusetts that argued for equality. Today their logic looks undeniable.

Just as the colonists desired freedom from the English Crown, black slaves merited the right to self-determine. According to Sesay, these petitions “surely must have arisen from some sense of hope or optimism that action would bring change.”

Despite the nation’s emancipation from England, slavery’s end in America would be delayed by nearly 100 years. This is the stinging nature of hope. Any social transformation fueled by it will take time. Early abolitionists of the slave trade exercised “a discerning and pragmatic understanding of politics” as they shifted from individual lawsuits to a consistent attack on the institutions of slavery.

A 2017 Gallup poll reflects the African-American community’s unique relationship with hope. While whites, Asians and Hispanics expressed a life-satisfaction score of 7 out of 10, and an anticipated satisfaction scores of 7.6 to 8, African-Americans expressed a life-satisfaction score of 6.8, but had the highest anticipated satisfaction of 8.4. The index of anticipation reflected expectations for the next five years.

—