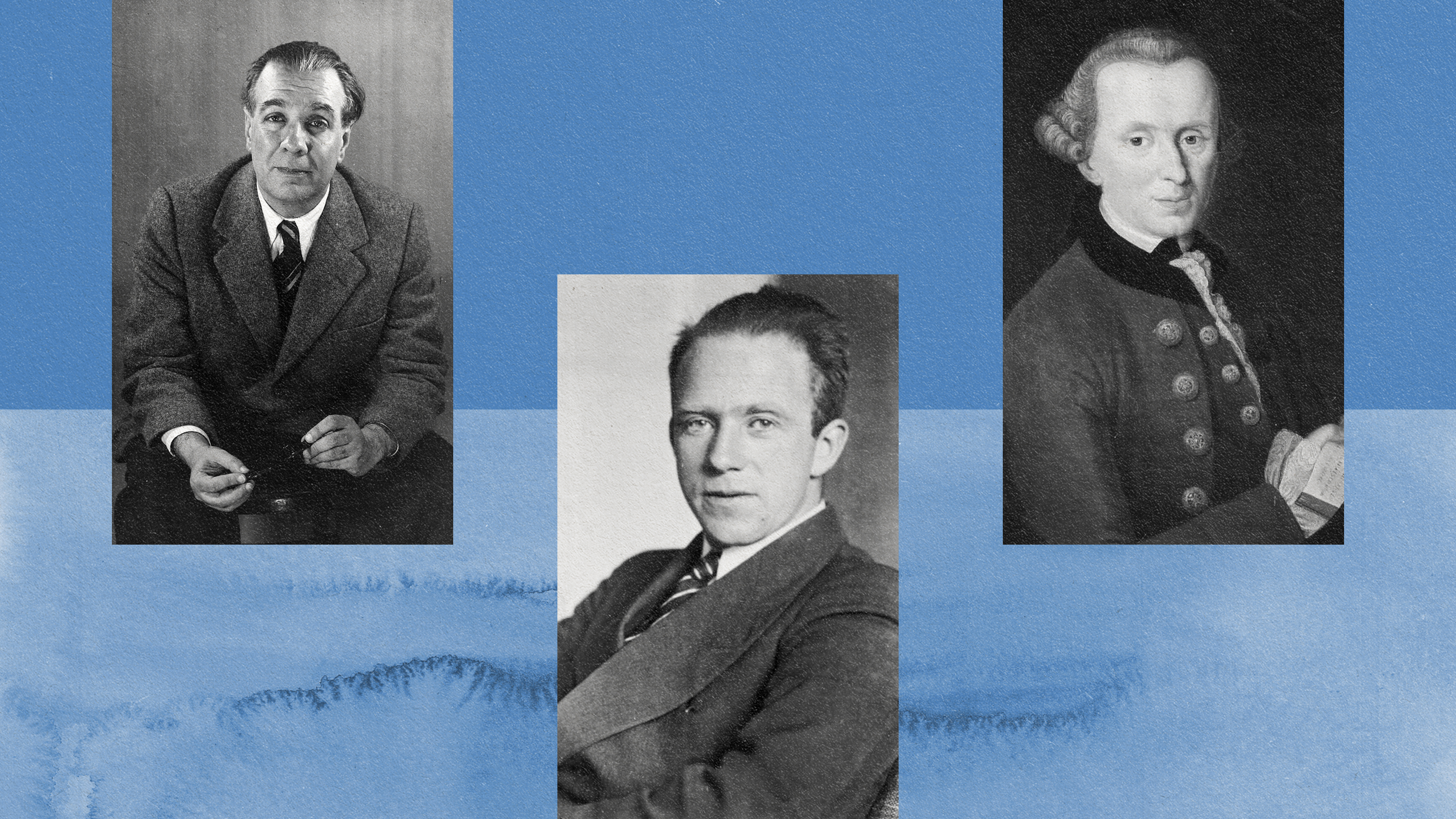

Surprisingly modern lessons from classic Russian literature

Credit: George Cerny via Unsplash

- Russian literature has a knack for precisely capturing and describing the human condition.

- Fyodor Dostoevsky, Leo Tolstoy, and Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn are among the greatest writers who ever lived.

- If you want to be a wiser person, spend time with the great Russian novelists.

In Fyodor Dostoevsky’s 1864 novella Notes from Underground, an unnamed narrator asks the following question: “What can be expected of man since he is a being endowed with strange qualities?” The answer: “Even if man were nothing but a piano-key and this were proved to him by science, even then he would not become reasonable, but would purposefully do something perverse out of simple ingratitude. He would contrive destruction and chaos only to gain his point!”

After reading another handful of equally puzzling paragraphs, chances are you will find yourself seriously considering whether or not to put down this 100-page riddle. Chances are, plenty of readers will have beaten you to it already. Keep on reading, however, and you might just find that the second half of the story is not only much, much easier to understand, but can also make you look back at the first half from a radically different perspective.

A small person with big power

This narrator, it turns out, is a proud but spiteful bureaucrat. Dissatisfied with his career, he uses the trivial bit of power his position bestows upon him to make life hell for those he interacts with. Eclipsed by former classmates who successfully climbed the ladders of the military and high society, he spends his days alone — lost inside his own head — thinking of reasons for why the world has yet to notice the extraordinary talents he believes he possesses.

After the narrator finishes his incoherent diatribe about society’s discontents, we get a glimpse at his everyday existence and the events that have made him so embittered. In one scene, he invites himself to a party for a recently promoted colleague he despises, only to spend the rest of the night complaining about the fact that everyone but him is having a fun time. “I should fling this bottle at their heads,” he thinks, reaching for some champagne and defeatedly pouring himself another round.

Angsty college students will recognize this kind of crippling social anxiety in an instance, leaving them amazed at the accuracy with which this long-dead writer managed to put their most private thoughts to paper. Dostoevsky’s unparalleled ability to capture our murky stream of consciousness has not gone unnoticed; a century ago, Sigmund Freud developed the study of psychoanalysis with Notes in the back of his mind. Friedrich Nietzsche listed Dostoevsky as one of his foremost teachers.

To an outsider, Russian literature can seem hopelessly dense, unnecessarily academic, and uncomfortably gloomy. But underneath this cold, rough, and at times ugly exterior, there hides something no thinking, feeling human could resist: a well-intentioned, deeply insightful, and relentlessly persistent inquiry into the human experience. Nearly two hundred years later, this hauntingly beautiful literary canon continues to offer useful tips for how to be a better person.

Dancing with death

Some critics argue that the best way to analyze a piece of writing is through its composition, ignoring external factors like the author’s life and place of origin. While books from the Russian Golden Age are meticulously structured, they simply cannot be studied in a vacuum. For these writers, art did not exist for art’s sake alone; stories were manuals to help us understand ourselves and solve social issues. They were, to borrow a phrase popularized by Vladimir Lenin, mirrors to the outside world.

Just look at Dostoevsky, who at one point in his life was sentenced to death for reading and discussing socialist literature. As a firing squad prepared to shoot, the czar changed his mind and exiled him to the icy outskirts of Siberia. Starting life anew inside a labor camp, Dostoevsky developed a newfound appreciation for religious teachings he grew up with, such as the value of turning the other cheek no matter how unfair things may seem.

Dostoevsky’s brush with death, which he often incorporated into his fiction, was as traumatizing as it was eye-opening. In The Idiot, about a Christ-like figure trying to live a decent life among St. Petersburg’s corrupt and frivolous nobles, the protagonist recalls an execution he witnessed in Paris. The actual experience of standing on the scaffold — how it puts your brain into overdrive and makes you wish to live, no matter its terms and conditions — is described from the viewpoint of the criminal, something Dostoevsky could do given his personal experience.

Faith always played an important role in Dostoevsky’s writing, but it took center stage when the author returned to St. Petersburg. His final (and most famous) novel, The Brothers Karamazov, asks a question which philosophers and theologians have pondered for centuries: if the omniscient, omnipotent, and benevolent God described in the Bible truly exists, why did He create a universe in which suffering is the norm and happiness the exception?

To an outsider, Russian literature can seem hopelessly dense, unnecessarily academic, and uncomfortably gloomy. But underneath this cold, rough, and at times ugly exterior, there hides something no thinking, feeling human could resist: a well-intentioned, deeply insightful, and relentlessly persistent inquiry into the human experience. Nearly two hundred years later, this hauntingly beautiful literary canon continues to offer useful tips for how to be a better person.

It is a difficult question to answer, especially when the counterargument (that is, there is no God) is so compelling. “I don’t want the mother to embrace the man who fed her son to dogs,” Ivan, a scholar and the novel’s main skeptic, cries. “The sufferings of her tortured child she has no right to forgive; she dare not, even if the child himself were to forgive! I don’t want harmony. From love for humanity, I don’t want it. I would rather be left with unavenged suffering.”

Yet it was precisely in such a fiery sentiment that Dostoevsky saw his way out. For the author, faith was a never-ending battle between good and evil fought inside the human heart. Hell, he believed, was not some bottomless pit that swallows up sinners in the afterlife; it describes the life of someone who is unwilling to forgive. Likewise, happiness did not lie in the pursuit of fame or fortune but in the ability to empathize with every person you cross paths with.

On resurrection

No discussion of Russian literature is complete without talking about Leo Tolstoy, who thought stories were never meant to be thrilling or entertaining. They were, as he wrote in his 1897 essay What is Art?, “a means of union among men, joining them together in the same feelings.” Consequently, the only purpose of a novel was to communicate a specific feeling or idea between writer and reader, to put into words something that the reader always felt but never quite knew how to express.

Tolstoy grew up in a world where everything was either black or white and did not start perceiving shades of grey until he took up a rifle in his late teens. Serving as an artillery officer during the Crimean War, he found the good in soldiers regardless of which side of the conflict they were on. His Sevastopol Sketches, short stories based on his time in the army, are neither a celebration of Russia nor a condemnation of the Ottomans. The only hero in this tale, Tolstoy wrote, was truth itself.

It was an idea he would develop to its fullest potential in his magnum opus, War and Peace. Set during Napoleon’s invasion of Russia, the novel frames the dictator, who Georg Hegel labeled “the World Spirit on horseback,” as an overconfident fool whose eventual downfall was all but imminent. It is a lengthy but remarkably effective attack aimed at contemporary thinkers who thought history could be reduced to the actions of powerful men.

Semantics aside, Tolstoy could also be deeply personal. In his later years, the writer — already celebrated across the world for his achievements — fell into a depression that robbed him of his ability to write. When he finally picked up a pen again, he did not turn out a novel but a self-help book. The book, titled A Confession, is an attempt to understand his increasingly unbearable melancholy, itself born from the grim realization that he — like everyone else — will one day die.

In one memorable paragraph, Tolstoy explains his situation through an Eastern fable about a traveler climbing into a well to escape from a vicious beast, only to find another waiting for him at the bottom. “The man, not daring to climb out and not daring to leap to the bottom, seizes a twig growing in a crack in the wall and clings to it. His hands are growing weaker and he feels he will soon have to resign himself to the destruction that awaits him above or below, but still he clings on.”

Confession is by no means an easy read, yet it is highly recommended for anyone feeling down on their luck. Tolstoy not only helps you understand your own emotions better but also offers inspiring advice on how to deal with them. What makes us humans unique from all other animals, he believes, is the ability to grasp our own impending and inevitable death. While this knowledge can be a terrible burden, it can also inspire us to focus on what is truly important: treating others with kindness.

Urge for action

Because 19th century Russia was an autocracy without a parliament, books were the only place people could discuss how they think their country should be run. While Tolstoy and Dostoevsky made conservative arguments that focused on personal growth, other writers went in a different direction. Nikolay Chernyshevsky, a progressive, treated his stories like thought experiments. His novel, What is to be Done?, explores what a society organized along socialist lines could look like.

What is to be Done?, which Chernyshevsky wrote while he was in prison, quickly became required reading for any aspiring Russian revolutionary. Imbued with the same kind of humanistic passion you may find in The Brothers Karamazov, these kinds of proto-Soviet blueprints painted such a convincing (and attractive) vision for the future that it seemed as though history could unfold itself no other way than how Karl Marx had predicted it would.

“I don’t know about the others,” Aleksandr Arosev, a Bolshevik who saw himself as the prophet of a new religion, once wrote about his childhood reading list, “but I was in awe of the tenacity of human thought, especially that thought within which there loomed something that made it impossible for men not to act in a certain way, not to experience the urge for action so powerful that even death, were it to stand in its way, would appear powerless.”

Decades later, another Aleksandr — Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn — wrote an equally compelling book about the years he spent locked inside a Siberian prison camp. Like Arosev, Solzhenitsyn grew up a staunch Marxist-Leninist. He readily defended his country from Nazi invaders in East Prussia, only to be sentenced to eight years of hard labor once the government intercepted a private letter in which he questioned some of the military decisions made by Joseph Stalin.

In the camp, Solzhenitsyn took note of everything he saw and went through. Without access to pen and paper, he would lie awake at night memorizing the pages of prose he was composing in his mind. He tried his best remember each and every prisoner he met, just so he could tell their stories in case they did not make it out of there alive. In his masterpiece, The Gulag Archipelago, he mourns the names and faces he forgot along the way.

Despite doing time for a crime he did not commit, Solzhenitsyn never lost faith in humanity. Nor did he give in to the same kind of absolutist thinking that led the Soviet Union to this dark place. “If only it were all so simple!” he wrote. “If only there were evil people somewhere insidiously committing evil deeds. But the line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being. And who is willing to destroy a piece of his own heart?”

The mystery of man

“All mediocre novelists are alike,” Andrew Kaufman, a professor of Slavic Languages and Literature at the University of Virginia, once told The Millions. “Every great novelist is great in its own way.” This is, in case you didn’t know, an insightful spin on the already quite insightful opening line from another of Tolstoy’s novels, Anna Karenina: “All happy families are alike, but every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.”

While Russian writers may be united by a prosaic style and interest in universal experience, their canon is certainly diverse. Writing for The New York Times, Francine Prose and Benjamin Moser neatly sum up what makes each giant of literature distinct from the last: Gogol, for his ability to “make the most unlikely event seem not only plausible but convincing”; Turgenev, for his “meticulously rendered but ultimately mysterious characters”; Chekhov, for his “uncanny skill at revealing the deepest emotions” in his plays.

As distant as these individuals may seem to us today, the impact they made on society is nothing short of profound. In the cinemas, hundreds of thousands gather to watch Keira Knightly put on a brilliant ballgown and embody Tolstoy’s tragic heroine. At home, new generations read through Dostoevsky’s Notes of Underground in silence, recognizing parts of themselves in his despicable but painfully relatable Underground Man.

Just as Tolstoy needed at least 1,225 pages to tell the story of War and Peace, so too does one need more than one article to explain what makes Russian literature so valuable. It can be appreciated for its historical significance, starting a discussion that ended up transforming the political landscape of the Russian Empire and — ultimately — the world as a whole. It also can be appreciated for its educational value, inspiring readers to evaluate their lives and improve their relationships.

Most importantly, perhaps, Russian literature teaches you to take a critical look at yourself and your surroundings. “Man is a mystery,” Dostoevsky once exclaimed outside his fiction, reiterating a teaching first formulated by the Greek philosopher Socrates. “It must be unraveled. And if you spend your whole life unraveling it, do not say you have wasted your time. I occupy myself with this mystery, because I want to be a man.”