Is Dumbledore gay? The question highlights a deeper literary debate

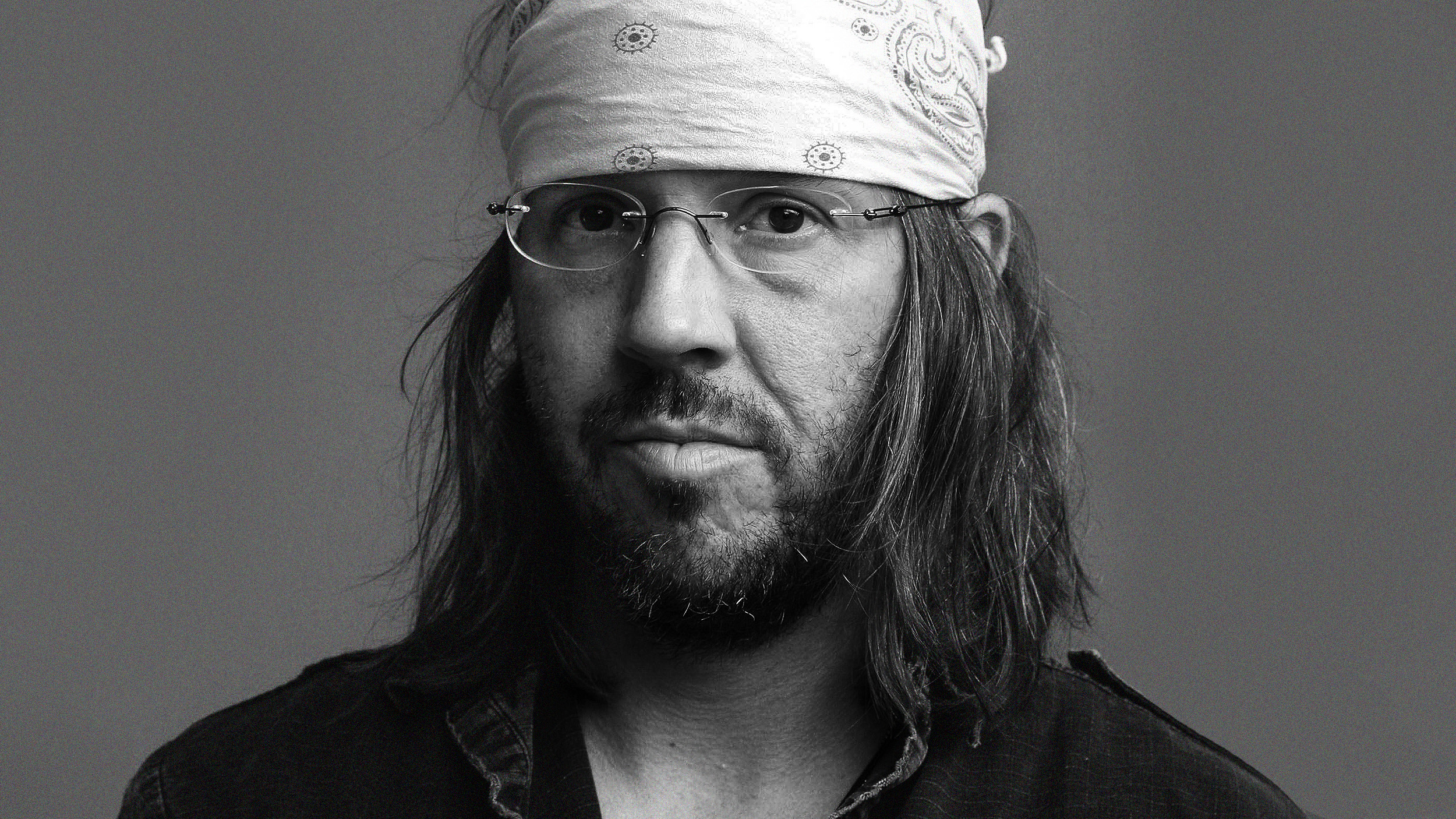

Credit: Bruno Vincent via Getty Images

- Intentionalism is the view that authors have a special authority over their work and can determine what is or is not the “proper” meaning to be found.

- Anti-intentionalism is the view that “there is nothing outside the text,” and that while the author might be important, they are no more authoritative than the reader in determining meaning.

- The joy and wonder of reading is how we all find our own meanings in literature. We find answers and truths that no one else can define for us.

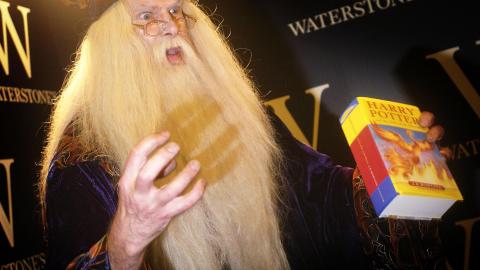

In 2007, J.K. Rowling rather shocked the world when she announced that one of the biggest characters in her Harry Potter books, Albus Dumbledore, was gay. Up to that point, there was nothing in the text that explicitly mentioned his sexuality one way or another. There were barely any hints at all. But, her wording was interesting in itself. She said, “I always thought of Dumbledore as gay.” She didn’t say he definitely was. She didn’t say that’s the only way to see things. She said it was just how she saw him.

This raises one big issue in the philosophy of literature and in literary interpretation generally: to what extent can an author determine what their work means, especially after it’s published? Do they have a special authority on how and how not to interpret a work?

Broadly speaking, the debate falls down into two camps: intentionalism and anti-intentionalism.

Intentionalism: What the author says, goes

Intentionalism is the idea that by creating the work of literature, the author has a special say over how to interpret that work. The strongest form of this is that the author has the only say. One is reminded of Humpty Dumpty in Lewis Carrol’s Through the Looking Glass as he says, “When I use a word it means just what I choose it to mean — neither more nor less.” This applies especially to poetry, allegory, and metaphor. When a poet uses the word “moon,” who determines what this might stand for?

If intentionalism were true, it would somewhat destroy the entire discipline of literary criticism.

In practice, few philosophers or critics hold this strong view. It’s ridiculous to assume an author can say “dog” actually means “pineapple” and for that to be true. What’s a more compelling case is a form of weak intentionalism that says an author has a privileged interpretation of their work. For instance, if there are two compelling interpretations of a work, the author has the final say. If some people see Narnia as a Christian allegory and others see it as a Marxist one, then C.S. Lewis saying it’s about Christ would resolve the issue. So, if Rowling says Dumbledore is gay, then so long as that’s a reasonable interpretation, that’s the final word on the matter.

The intentionalist view seems plausible, if we consider how knowing an author’s plan changes our reading of the book. If we know that Fydor Dostoyevsky intended Prince Myshkin in The Idiot to be a near perfect moral exemplar “with an absolutely beautiful nature,” this colors how we see the book. Knowing that George Orwell intended the characters of Animal Farm to be stand-ins for figures of the Russian Revolution sets you up to read the book in a certain way.

What’s more, readers seem to love asking authors questions like, “What did you mean when such-and-such did this?” or, “What were your intentions in this scene?” Clearly the author’s intentions do matter more than we think, at least to some people.

Anti-intentionalism: The author has no special authority

On the other side of the debate is the idea that once a work of literature is “out there,” the author has no special jurisdiction or power over how the reader should interpret it. As Philip Pullman wrote, “The meaning is what emerges from the interaction between the words I put on the page and the readers’ own minds as they read them.”

This “anti-intentionalism” is represented best by a seminal text, “The Intentional Fallacy,” by William Wimsatt, Jr. and Monroe Beardsley. In it, they provide various counter-examples that aim to show how what the author thought or intended cannot affect how we read their work.

For instance, the 18th century poet Mark Akenside used the word “plastic” to mean a very particular thing (which was “to be capable of change”). Today, of course, that word has come to be much more commonly associated with something else entirely. The word has moved on from Akenside’s day, and so we can say his poem means something new. Likewise, in Kublai Khan by Samuel Taylor Coleridge, many of the passages are references to other poems. Many readers might not know this but still are perfectly capable of finding meaning in the poem.

In both cases, the anti-intentionalist view can be summarized by the philosopher Jacques Derrida’s line, “There is nothing outside the text.” Or, put another way, the author loses control over their work once we read it.

Intentionalism would destroy literary criticism

The biggest issue, perhaps, is that if intentionalism were true, it would somewhat destroy the entire discipline of literary criticism.

For example, John Milton’s Paradise Lost explicitly opens with the words that his poem is about “justifying the ways of God to men.” Yet, Percy Shelley and William Blake reinterpreted the entire thing as actually having Satan as the hero! If the author were dictator of their work, this kind of reimagining would never be possible. If an author claiming, “This is what the book means,” were the final say, it would disallow any kind of fresh perspective or exciting re-readings. There would be no psychoanalytic interpretation of Hamlet or feminist perspectives on Tennessee Williams.

But most of all, if the author’s intentions were all that mattered, no one would be able to find their own interpretations of a work. The beauty of literature is how we all project ourselves into what we’re reading. We find answers and truths in there that are specific to us. In a way, the book becomes part of you, the reader.

So, Dumbledore can be gay but not because J.K. Rowling thinks so. It’s only true if you see it, too.

Jonny Thomson teaches philosophy in Oxford. He runs a popular Instagram account called Mini Philosophy (@philosophyminis). His first book is Mini Philosophy: A Small Book of Big Ideas.