4 writers who pushed dark humor to its absolute limits

- Thanks to streaming services and stand-up, dark humor is more popular today than ever before.

- But dark humor, also known as black comedy, can be found in classic literature, where the tradition originally flourished.

- From Seneca to Charles Bukowski, these writers demonstrate the power of dark humor.

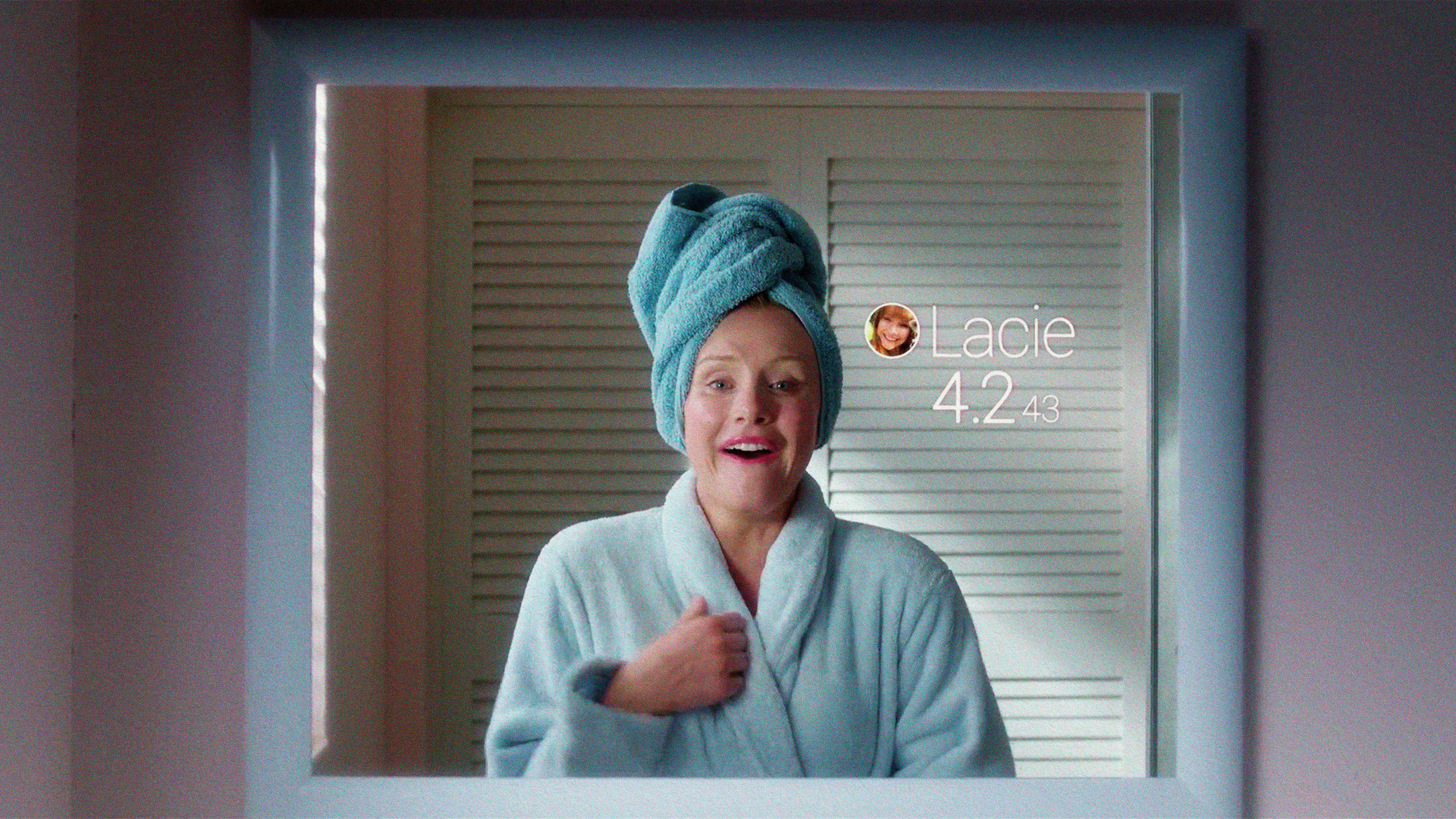

After Life is a comedy series on Netflix created by British comedian Ricky Gervais about a middle-aged man who contemplates suicide after his wife dies of cancer. Although the premise doesn’t sound all that funny, After Life is most certainly a comedy — a black comedy, to be precise.

Loosely speaking, black comedy is comedy that pokes fun at subjects which in any other context wouldn’t be considered humorous, such as death, disease, or discrimination. But black comedy — alternatively called dark humor — is easier to spot than it is to define. Gervais’ character, a local news reporter, telling someone he’s interviewing that their ability to play the flute with their nose has made him think twice about killing himself, is an example of dark humor, as are the following jokes Gervais has told outside of After Life:

“Remember, if you don’t sin, then Jesus died for nothing.”

“Being healthy is basically dying as slowly as possible.”

“Mondays are fine. It’s your life that sucks.”

Sometimes, dark humor makes us laugh because it’s honest. Once taboo, nowadays dark humor is everywhere, from television (Barry, The Boys, The Inbetweeners) to films (The Menu, Triangle of Sadness, The Banshees of Inisherin) to stand-up (John Mulaney’s latest show pokes fun at his succumbing to then narrowly recovering from drug addiction).

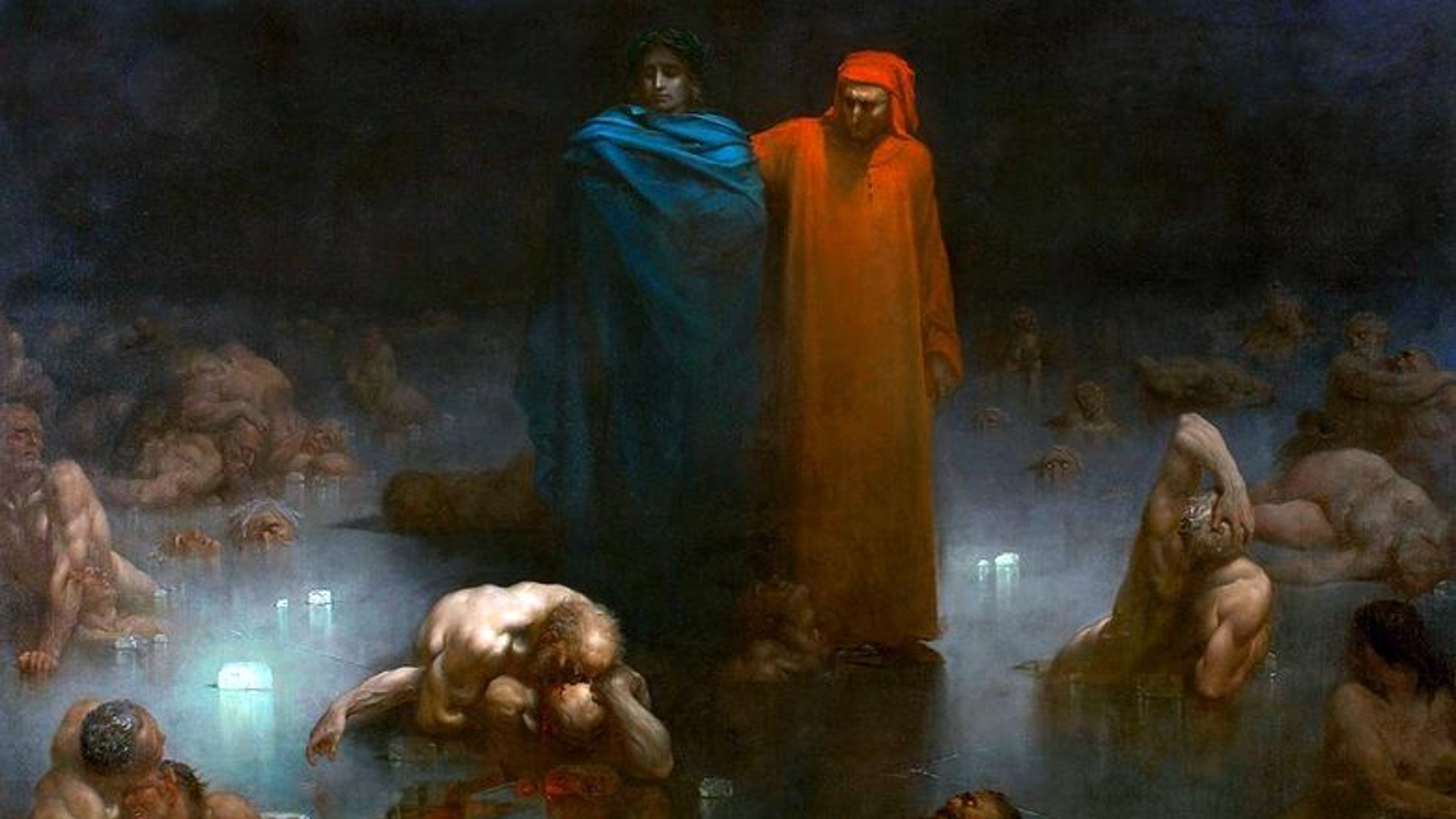

But before dark humor became popular in comedy clubs and on streaming services, it was the stuff of literature. There are a surprising number of books so twisted that they make the bleakest scenes from After Life feel as bright and bubbly as an episode of Sesame Street.

Thyestes by Seneca

In this fabula crepidata — the Roman equivalent of a Greek tragedy — Thyestes is recalled from exile to dine with his brother Atreus, who for political reasons not only kills the former’s sons, but also tricks him into eating their remains. As Thyestes catches up to what the audience already knows, Atreus caters a separate course of puns, innuendos, and double entendres. He assures his brother “no part” of his children will be kept away from him, and that he will be “filled” with their presence. He also promises Thyestes that he’ll soon see their “faces” again, only to present him with their severed heads. As far as Atreus is concerned, this act of familial cannibalism is a fitting punishment for Thyestes’ “appetite” for power.

What strikes modern readers as exceptionally gruesome may well have made a lighter impression on the ancient Greeks and Romans, who lived in a world that was much more accustomed to (and tolerant of) suffering and injustice. A Stoic philosopher who preached acceptance and level-headed confrontation of the many challenges that life inevitably throws your way, Seneca — who was forced to commit suicide by his mad pupil, Nero — probably understood that laughing in the face of adversity can be more helpful than complaining about it.

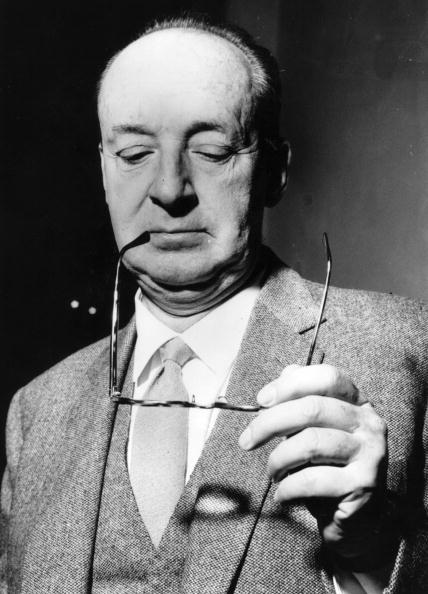

Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov

Russian literature is surprisingly humorous, so much so that reading Fyodor Dostoevsky aloud with a group of friends is a lot more entertaining than you might think. Tolstoy, though stiffer, wasn’t bad either. In an early scene from War and Peace, two drunken characters tie a policeman to the back of a bear before dumping the bear into a river.

But Russian literature is also deadly serious, dealing with matters of life, death, and the nature of God. As such, it’s fertile soil for black comedy. Nikolai Gogol’s short story, Diary of a Madman, chronicles a civil servant’s hilarious descent into insanity. The ending of Anton Chekhov’s play The Seagull, in which the main character shoots himself off-stage, can and has been played for laughter in addition to shock. The list goes on and on.

However, no piece of Russian literature gets quite as dark as Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita, which features the extremely dark wordplay of pedophile Humbert Humbert, who refers to Dolores, the 12-year-old he is grooming, as his “aging mistress.” Trying to pass her off as his own daughter, he describes her to a different character as the product of “a mad love affair.” And as if all that wasn’t terrible enough, Nabokov includes scenes where Humbert states that Dolores “craved for fresh fruits,” and watches her eat a banana.

Anything by Charles Bukowski

Born in Andernach, Germany in 1920 to an American father and German mother, Charles Bukowski moved to the impoverished underbelly of Los Angeles when he was three years old and grew up during the Great Depression. He was regularly and sadistically beaten by his father for the smallest non-transgressions, like missing a blade of grass while mowing the front lawn, and — after achieving decent success writing about drunkenness — temporarily gave up writing to become a full-time drunkard, traveling the country and scoring free beers by letting bartenders beat him up in front of crowds.

Bukowski translated his awful yet colorful life experiences into engaging fiction and poetry, with titles like “Love is a Dog From Hell” and “Play the Piano Drunk Like a Percussion Instrument Until the Fingers Begin to Bleed a Bit.” His dark humor shines through even in interviews. “I get many letters in the mail about my writing,” he remarked in 1981, “and they say: ‘Bukowski, you are so f***ed up and you still survive. I decided not to kill myself.’… So in a way I save people… Not that I want to save them: I have no desire to save anybody…”

He rejected on principle the notion of poetry as a craft that should be labored over and revised. When Bukowski wrote poems, he wrote 15 in a row — all while intoxicated. Black comedy, manifesting in the form of brutal honesty, was his weapon of choice. Hypocrisy — social, religious, and literary — was his primary target.

In Case of Emergency by Mahsa Mohebali

It’s one thing to go through withdrawal after developing a drug dependency, and quite another to go through withdrawal while society itself is falling apart around you. Usually, the former merely makes it seem as though the latter is also happening. But for recovering opium addict Shadi, the wider world is actually crumbling as, the morning she wakes up to an empty stash, earthquakes shake the city of Tehran.

In Case of Emergency, which came out in 2021, highlights the arguably most important benefit of dark humor: its ability to question social conventions. Just as Gervais’ character in After Life uses the death of his wife as an excuse to say whatever he thinks, even if it’s inappropriate or offensive, so too does Mahsa Mohebali’s novel take a hard look at sociopolitical issues that cannot be acknowledged openly in Iran.