Dante’s “Divine Comedy” isn’t only about religion. It’s a political statement.

- The real-life individuals Dante encounters in heaven and hell betray his political viewpoints.

- He opposed the aspirations of Pope Boniface VIII and longed for the Church to focus on the afterlife rather than earthly riches.

- Politically, he was nostalgic for the heyday of the Roman Republic, when leaders were loyal not to themselves but to the Republic.

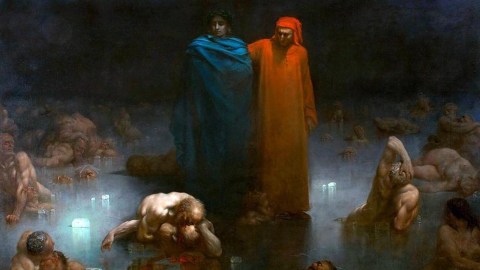

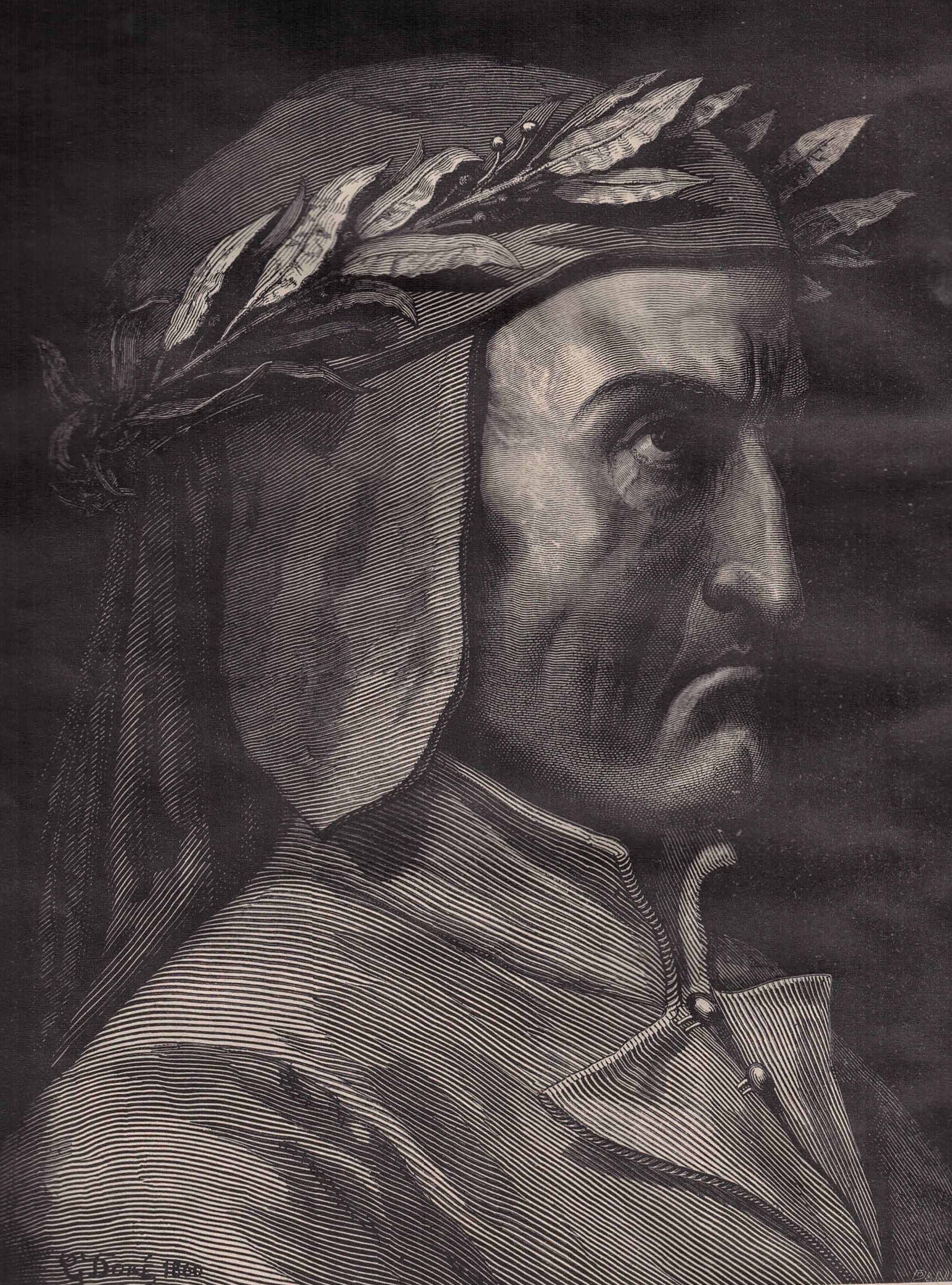

In the epic poem The Divine Comedy, Florentine poet Dante Alighieri journeys through hell, purgatory, and heaven. First published in 1320, the poem is best known today for its detailed depiction of the Christian afterlife. Especially memorable is hell, which Dante organizes into nine circles or levels reserved for different types of sinners.

The first circle, limbo, is reserved for otherwise decent people whose only sin was never converting to Christianity. After limbo comes lust, gluttony, greed, anger, heresy, violence, fraud, and — finally — treachery. Each circle comes with aesthetics and punishments that correspond to the crimes of its inhabitants. The souls condemned to lust are threshed by hurricanes that reflect the carnal desires that blew them aimlessly through life. In treachery, hell’s very bottom, Lucifer is frozen from the waist down in a lake of his own icy tears.

But The Divine Comedy isn’t just about the afterlife; it also tells us a great deal about the world of the living and of the author. During his journey, Dante encounters various real-life individuals from his own time and before. Chief among these is the pagan (and therefore limbo-bound) Roman poet Virgil, who guides Dante through hell and purgatory. Dante also encounters Beatrice, his first love, who died young and guides him through heaven. Some of the characters he meets are mythical, such as Minos, the legendary king of Crete, who judges the dead. Others are historical: Brutus and Cassius, who betrayed Julius Caesar, are found in treachery where they are being gnawed on by two of Satan’s three jaws. Others still are personal: Dante finds Filippo Argenti, his former rival, drowning in the river Styx.

The real-life individuals Dante runs into during his spiritual journey — not to mention their ascribed place in the afterlife — betray the author’s opinions on temporal matters such as history and politics. Dante was a deeply religious person, but he was not a monk who sought to approach god by isolating himself from the wider world. His religiosity was narrowly intertwined with civil society even if, at the end of the day, he argued the two ought to remain administratively separated.

Dante’s Yelp reviews

Whenever Dante comes across fellow Italians in hell, he rarely has anything good to say about them or the cities they hail from. In fraud, a demon comes to deliver the soul of “one of Santa Zita’s Elders,” adding he will be right back with more. In treachery, Dante learns the circle has already marked off a spot in the ice for one Branca Doria, even though this man from Genoa is still alive. Dante laments:

“Ah Genoese! Men perverse in every way, / With every foulness stain’d, why from the earth / Are ye not cancel’d? Such an one of yours / I with Romagna’s darkest spirit found, / As for his doings even now in soul / Is in Cocytus plung’d, and yet doth seem / In body still alive upon the earth.”

Ever the arbiter, Dante speculates that corruption is in Genoa’s DNA and even wonders if it would be best to raze the city to the ground.

Critics debate the extent to which Dante’s judgment is rooted in prejudice. Dante’s disgust for Pisa, which he hopes will be destroyed when the islands of Caprara and Gorgona block the mouth of the Arno River, can be explained not by the apparent sinfulness of its people — how does one even verify such a blanketed value judgment? — but by, to quote Anthony J. De Vito, “the traditional feeling of rivalry and enmity which existed between Florence and Pisa, which Dante shared.”

Then again, Dante didn’t show much love for his hometown, either. In his version of hell, Florentines are ubiquitous, and Florence is infamous. The city is said to have been built by Satan, and its shortcomings are described in a language that borders on coarse: a stark contrast with the elevated style deployed elsewhere in The Divine Comedy. Needless to say, Dante’s unfavorable Yelp reviews did not sit well with many of his earliest readers.

The good old days

The only cities that Dante discusses positively are those with a clear connection to the Roman Empire. He describes Mantua, the birthplace of Virgil, as a place of harmony. At the same time, he scorns Padua for rejecting the imperial order the Romans passed down onto Italy through — in the author’s eyes — Can Francesco della Scala, ruler of Verona.

Greatest of all was Rome itself, which received special treatment from Dante. Indeed, the poet judged the Eternal City not by the behavior of its residents, but by the ideas it continued to represent throughout ancient and medieval history. It was the birthplace of both an empire and a religion. More than that, it was the location where these institutions, which Dante perceived to be in decline, briefly existed in their ideal form.

“Despite his differences with those who occupied the chair of Saint Peter,” writes De Vito, “despite his contempt for the Roman curia, which neglected the pursuit of souls in its pursuit of temporal gains, Rome remains for Alighieri the great ideal of national glory and hope.”

Barbara Barclay Carter adds: “Dante would sigh as wistfully as a modern romantic for a vanished golden age of knightly honour and high endeavour.”

Dante’s nostalgia had two sides: one political and one spiritual. Politically, he yearned for the days of the Roman Republic, a time when leaders were driven not by glory or gain but by a commitment to the Republic and its citizens, a time when men like Cincinnatus could be granted dictatorial powers in moments of crises and trusted to renounce those powers once the crisis was averted. Dante’s admiration of ancient Rome can also be gleaned from his treatment of Brutus and Cassius, whose punishment is second only to Judas, the betrayer of Christ, who is imprisoned in Satan’s central mouth.

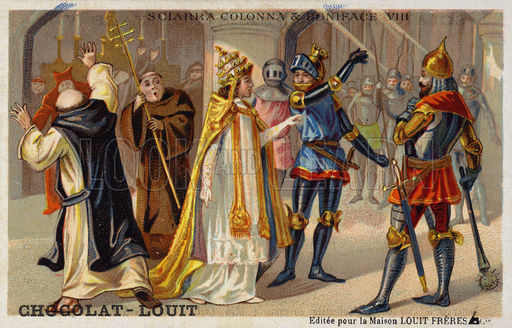

Spiritually, Dante wished for a Catholic Church that more closely mirrored the teachings of Christ. Instead of accumulating riches in the form of land and indulgences (essentially tickets to heaven), the institution should give away its material wealth and return to its original state of poverty and humility. More importantly, Dante argued that representatives of God — namely Pope Boniface VIII — had no business competing with kings and lords for temporal authority. Their domain was the afterlife, not Earth.

Dante’s views on the separation of church and state, fully explained in a text titled De Monarchia, are also present in The Divine Comedy. In hell, Boniface resides in the circle of fraud among the simoniacs: clerics who use their position to advance private interests. Meanwhile, in paradise, the apostle Peter, the Church’s founder, condemns the corruption that has infested his creation by the 14th century, placing his hopes in the same divine providence that guided the Roman general Scipio Africanus when Hannibal’s Carthaginian forces marched across the Alps.

Heavenly freedom

Of course, Dante wasn’t the only Italian thinking about these topics. At the time he was writing The Divine Comedy, Italy was split between two factions: the Guelphs and the Ghibellines. The Ghibellines recognized the Holy Roman Emperor as the ultimate authority, while the Guelphs answered to the Pope. The Guelphs, to which Dante belonged, were further divided between the moderate Whites, who championed pacification and reconciliation, and the Blacks, who sought to install Boniface as their one and only ruler.

The Black Guelphs, who did not shy away from violence, emerged as the victors of that clash. Dante, then an ambassador in Rome, was arrested and condemned to death. Although his execution never took place, he was cast out of Florence and left to wander from town to town, much like we find him at the beginning of The Divine Comedy, lost in a dark forest at the midpoint of life.

Finding conflict everywhere he went, Dante thought of Italy as “a ship without a pilot in a great storm.” De Vito writes that the chaos fueled the author’s desire for “a supreme coordinating authority, able to ensure that ‘life on this threshing-floor of mortality should be lived in freedom and peace.’”

This is how Dante finally arrived at his idea of heaven.