Boléro: Was Maurice Ravel’s famous music the product of a brain disease?

- Some suspect the repetitive structure of Ravel’s Boléro is a sign that the composer suffered from dementia.

- Over the years, many neuroscientists have analyzed the music in search of answers, but so far, there is no consensus on a diagnosis.

- The discussion surrounding Boléro is a testament to the illusive, mysterious, and contradictory nature of creative genius.

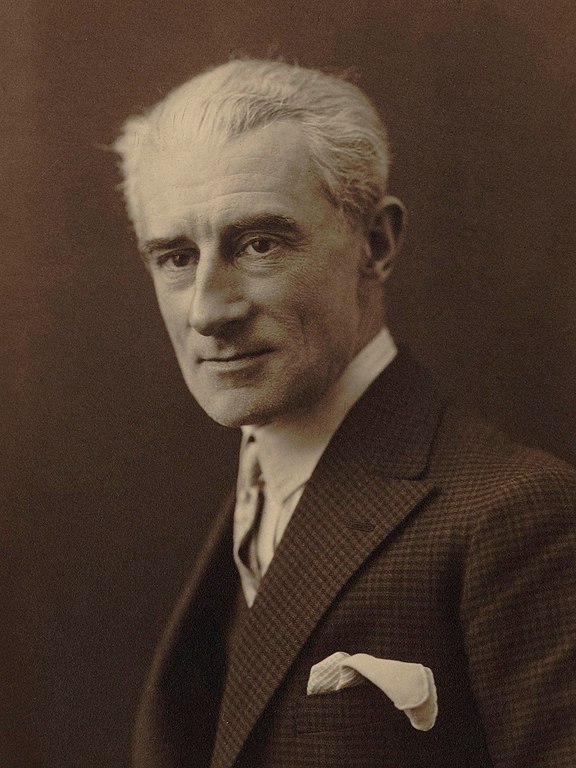

In 1928, Russian dancer and Parisian matron of the arts Ida Rubinstein asked famed composer Maurice Ravel to provide the music for a 15-minute performance based on a popular Spanish dance style. Initially, Ravel was to create a variation on the music of Isaac Albéniz, but copyright laws prevented him from doing so. When Rubinstein got permission from Albéniz himself, Ravel politely declined; he’d already begun working on something original and felt unable to stop.

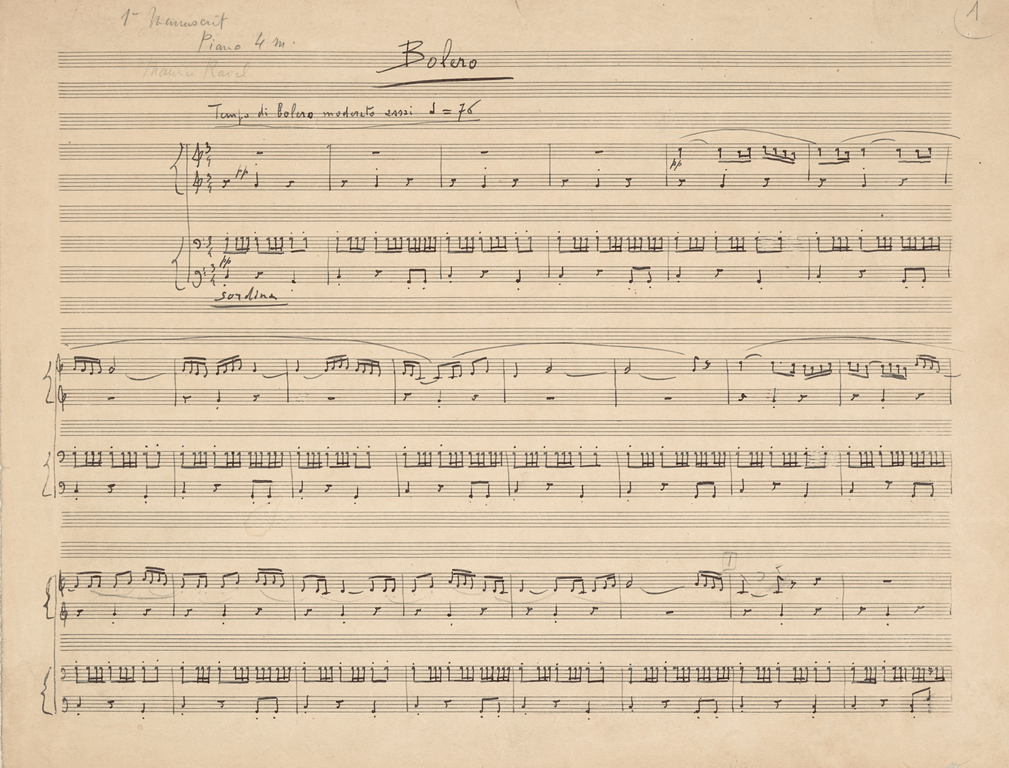

The composition that resulted from this partnership, Boléro, was jarring even by contemporary standards. The piece, in Ravel’s own words, was essentially “one long, very gradual crescendo” replete of contrast and invention. It provided a stark contrast to Ravel’s previous works as well as the standards of the time, which dictated compositions should avoid repeating themselves where possible.

Ravel’s experiment struck the right chord. Shortly after it was performed, Boléro was met with positive reviews from most critics. The provocative music also caught on with audience members and would go down in history as Ravel’s most famous and original piece of music. In recent years, the composition acquired additional significance as neuroscientists came to view its unusual structure as the expression of a deadly but still developing brain disease.

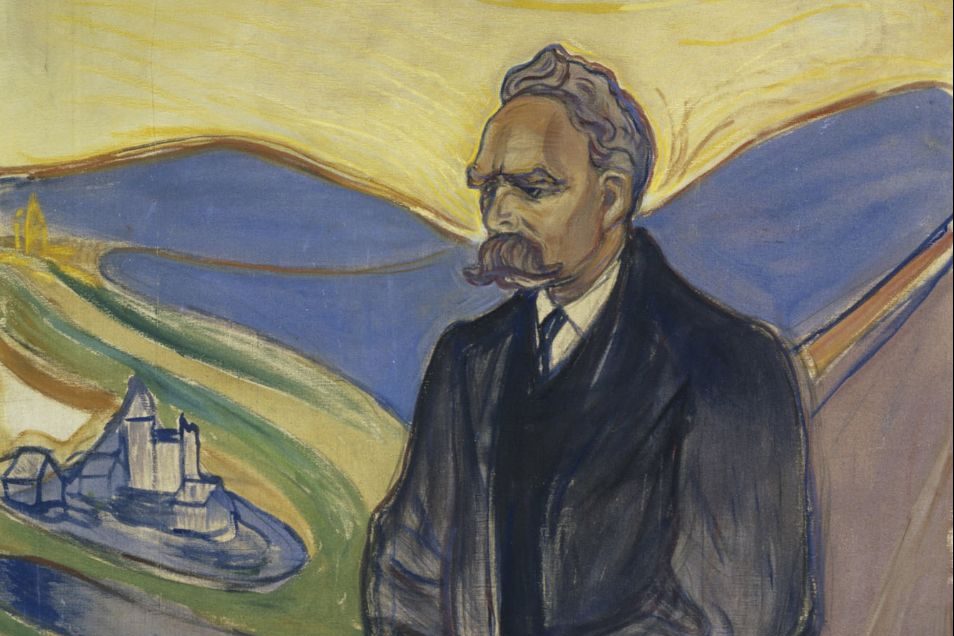

Maurice Ravel’s iconoclasm

At first glance, the birth of Boléro appears to be intentional rather than accidental. Its creation was not the result of a developing brain disease. Instead, the composition was created from Ravel’s characteristic desire to question and break with the dominant musical traditions of his time. Ravel’s achievements at the Paris Conservatoire were mediocre at best, much to the disappointment of his instructors. Oxford musicologist Barbara Kelly claimed of Ravel that he was “only teachable on his own terms.”

Ravel’s rebellious nature did not diminish with age. After leaving the Conservatoire, the composer joined Les Apaches, a group of Paris-based musicians and writers whose talent and vision had gone unrecognized by academic institutions. Though Ravel’s music often fell on deaf ears, he was markedly immune to external criticism. In his biography, Ravel: Man and Musician, musicologist Arbie Orenstein describes the composer as a uniquely single-minded, perfectionistic individual who listened to no one but his own gut.

Unsurprisingly, Ravel proved no less stubborn when composing Boléro. On holiday in Saint-Jean-de-Luz, he told his friend Gustave Samazeuilh that he wanted to craft a piece in which the theme would be repeated rather than developed, keeping audiences interested simply by adding instruments. Ravel knew he was being incessantly iconoclastic, and he was greatly surprised when Boléro became a success. According to Orenstein, the composer had privately suspected no self-respecting orchestra would perform it.

Ravel’s medical history

At the same time, Ravel had a history of physical and mental injuries, many of which interfered with his ability to compose music. In 1932, Ravel suffered a blow to the head during a traffic accident. Though this injury was deemed inconsequential at the time, some neurologists speculated it might have quickened the development of underlying medical issues such as aphasia (inability to understand speech), apraxia (inability to perform routine motor functions), agraphia (inability to write), and alexia (inability to read).

Before these issues became apparent on their own, they manifested in the form of a decrease in Ravel’s creative output. A year later, Ravel had to give up scoring the film Don Quixote because he was unable to keep up with its production schedule. These unpublished songs were the last bits of music Ravel composed before his death. Though doctors failed to diagnose his illness, the composer eventually underwent surgery to help with his symptoms. Complications related to the operation caused Ravel to fall into a coma, and he died at the age of 62.

Clovis Vincent, the renowned Parisian neurosurgeon who performed the fateful operation, expected to find a ventricular dilation. Today’s experts have a very different hypothesis: they suspect Ravel’s issues stemmed not from his heart but his brain, but disagree on whether he suffered from frontotemporal dementia, Alzheimer’s, or Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease.

Decoding Boléro

Which of these diseases Ravel actually suffered from is hard to say, not only because the composer is long dead but also because he lived during a time when our understanding of neuroscience and mental illness was not advanced enough to produce a reliable diagnosis. Still, many experts have searched the curious composition of Boléro for hints of specific illnesses — a practice that has yielded several compelling arguments.

The incessant repetition found in Boléro could be a sign of Alzheimer’s disease, which manifests in a number of subtle, seemingly harmless behavioral traits that worsen over time. One of these is a display of repetitive, compulsive behavior. Based on what we know about Ravel’s life and personality, this kind of behavior was not uncharacteristic of the composer, though it did reach concerning crescendos with Boléro.

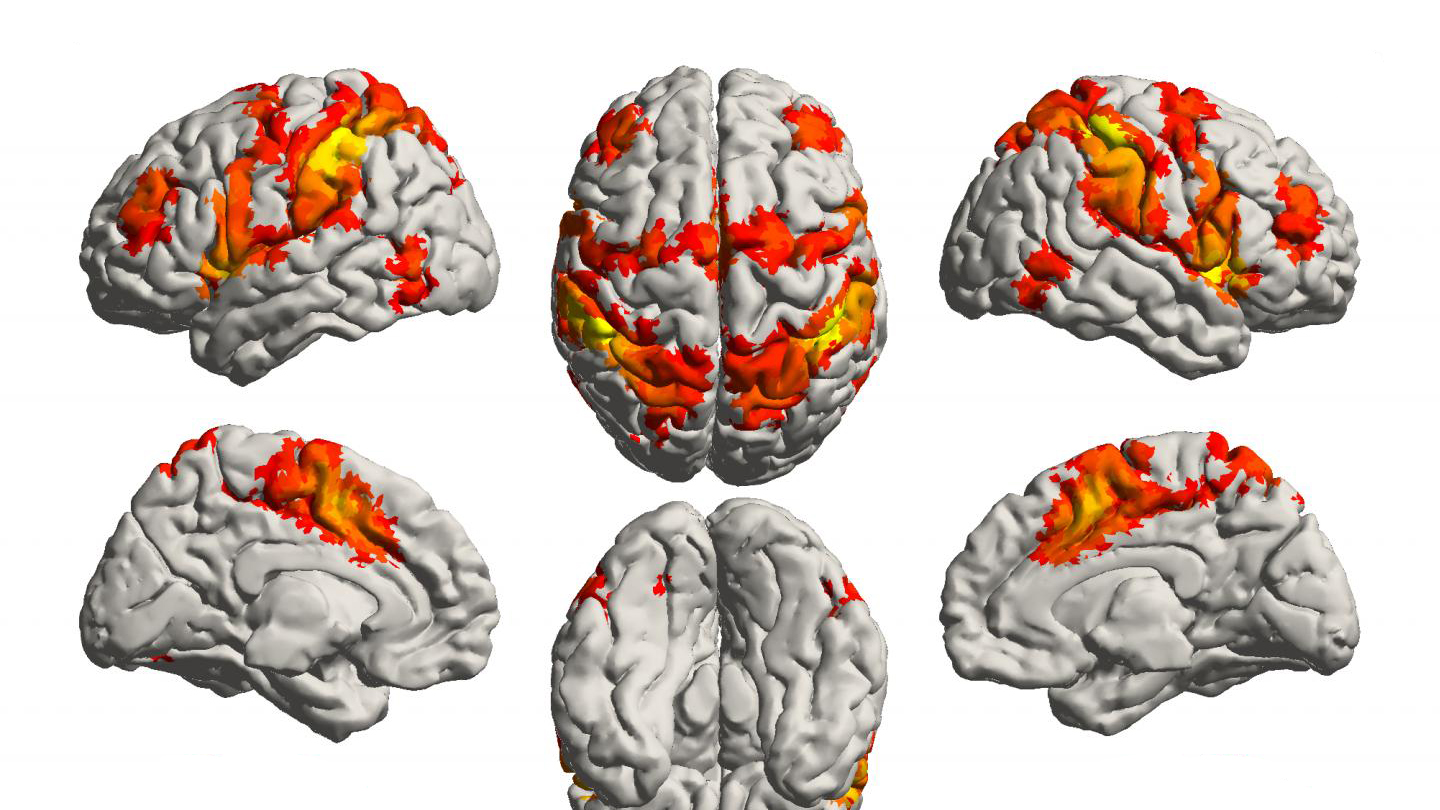

Francois Boller, a Clinical Professor of Neurology and Rehabilitation Medicine at the GW School of Medicine and Health Science, thinks that Ravel remained far too self-aware for a dementia patient, and suggests he may have suffered from a more complex illness instead, one affecting the left side of the brain. Boller’s evidence for this is the fact that Boléro is mostly focused on timbre, the aptitude for which stems from the brain’s right side.

The mysterious origins of creative genius

Boller’s diagnosis aligns with what we already know about the development of Ravel’s complications. Though the composer was unable to work, he spent the last few years of his life socializing with friends and family, something that most Alzheimer’s patients simply cannot do.

Boller says that Ravel “didn’t lose the ability to compose music” but merely “the ability to express it.” Songs are made up of various components, including rhythm, pitch, melody, and harmony. Our inclination toward each of these components is located in different parts of the brain, and studying which of these components ultimately failed Ravel could help us piece together his neuropsychological profile.

Of course, there remains the possibility that Boléro was created by a musician who, in mostly sound mind, decided he would experiment with the boundaries of his artistic medium. Throughout history, many forward-thinking artists — from Pablo Picasso to the sisters Brontë — were declared ill or mad by their short-sighted contemporaries. Their creativity leaves a decisive impact, while its source stays shrouded in mystery.