“Pure cinema”: Why Alfred Hitchcock thought the best films are silent

- Many film theorists argue that music and dialogue do not belong in a truly great film.

- This doctrine of pure cinema holds that filmmakers should focus on what makes their medium unique.

- This includes shot, montage, cinematography, and lighting, among other things.

Some of the most famous scenes in film history take place entirely without dialogue. Think of the quintessential Mexican standoff in Sergio Leone’s spaghetti Western classic The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, or the opening scene from Paul Thomas Anderson’s There Will Be Blood, in which a prospector played by Daniel Day-Lewis breaks his leg as he’s searching for silver. There is the gruesome bear attack in The Revenant, which won Leonardo DiCaprio his first Oscar, and the sequence from North by Northwest where the main character is chased by a crop duster. Action hero Tom Hardy has just 52 lines in Mad Max: Fury Road, and fewer than ten in Dunkirk.

In each of these examples, filmmakers chose to communicate through visuals what could have also been done with words. By doing so, they produced what Alfred Hitchcock — the director of North by Northwest — referred to as “pure cinema.”

Pure cinema is the belief that filmmakers should prioritize or even limit themselves to those elements that make films a unique artistic medium, like movement, cinematography, and lighting. Dialogue is disqualified because it encroaches on the domains of literature and, to a lesser extent, poetry. The goal of pure cinema is to make a film that cannot be translated into a book, just as the goal of pure literature would be to write a book that cannot be adapted into a film.

The concept of pure cinema originated during the silent era of 1894 to 1929. While some substituted spoken dialogue with text cards, skilled filmmakers figured out how to express themselves through images alone, developing a language that’s still spoken in theaters today. Pure cinema acquired a devoted following after the advent of talkies, with theorists arguing the addition of sound wasn’t just unnecessary but also marked the moment films became sources of entertainment rather than works of art. This is, of course, not entirely true. Even though a great many modern films, flavored with CGI and bombastic scores, lack the charming simplicity of the silent era, they still follow the same principles that guided Alfred Hitchcock.

Language of film

In a 1963 interview with the critic and filmmaker Peter Bogdanovich, Hitchcock described pure cinema as follows:

“You have a man look, you show what he sees, you go back to the man, you make him react in various ways. You see, you can make him look at one thing, look at another – without his speaking, you can show his mind at work, comparing things – any way you run there’s complete freedom. It’s limitless, I would say, the power of cutting and the assembly of images.”

His description echoes the philosophy of Soviet documentarian Dziga Vertov, who in his 1922 manifesto WE identified shot (image) and montage (the way images are stitched together in the editing room) as the medium’s primary building blocks. Vertov understood that montage was synonymous with meaning: show your audience a child followed by an elderly person, and you will make them think of the passage of time, just as a pile of food and an empty plate suggests the act of eating. Montage can be used to transmit more complex messages as well. In one of his own films, Vertov juxtaposes horses with train cars to convey the idea of progress. In another, he shows workers across the USSR going about their day to indicate a sense of solidarity between its culturally distinct and geographically isolated inhabitants, all without a single text card.

Wherever possible, Alfred Hitchcock approached filmmaking with the same mindset. In the opening of Rear Window, a film about a news photographer who sustains an injury on the job, the Master of Suspense opts to deliver his exposition through camerawork rather than dialogue. A single shot — moving from James Stewart’s face to his leg cast, to a broken camera on the table, and finally to pictures of racing cars toppled off the track — tells the audience who the film’s main character is, what he does for a living, and what caused his accident.

In an interview with François Truffaut, Hitchcock said he thought this approach was more interesting than if someone simply asked the character what happened to his leg:

“That would be the average scene. To me, one of the cardinal sins for a scriptwriter, when he runs into some difficulty, is to say, we can cover that by a line of dialogue. Dialogue should simply be a sound among other sounds, just something that comes out of the mouths of people whose eyes tell the story in visual terms.”

Pure cinema in the age of sound

As the moviegoing public flocked to the theaters to hear their favorite actors speak on-screen for the first time, Alfred Hitchcock and others worried the introduction of a new, nonvisual element in the language of cinema would completely transform the medium they knew and loved. “No power of speech is comparable to the descriptive value of photographs,” protested the silent filmmaker Paul Rotha, whose celebrated work risked turning obsolete. “Immediately a voice begins to speak in a cinema, the sound apparatus takes precedence over the camera, thereby doing violence to natural instincts.”

Hitchcock resisted the change for as long as he could, claiming he had no interest in making films that were essentially just “talking photographs.” Eventually, though, he realized that if he wanted to stay in business, he had to keep up with the times. He made his first sound film, Blackmail, in 1929. However, it wasn’t until the release of Psycho in 1960 that he began to grasp the full potential of sound in film.

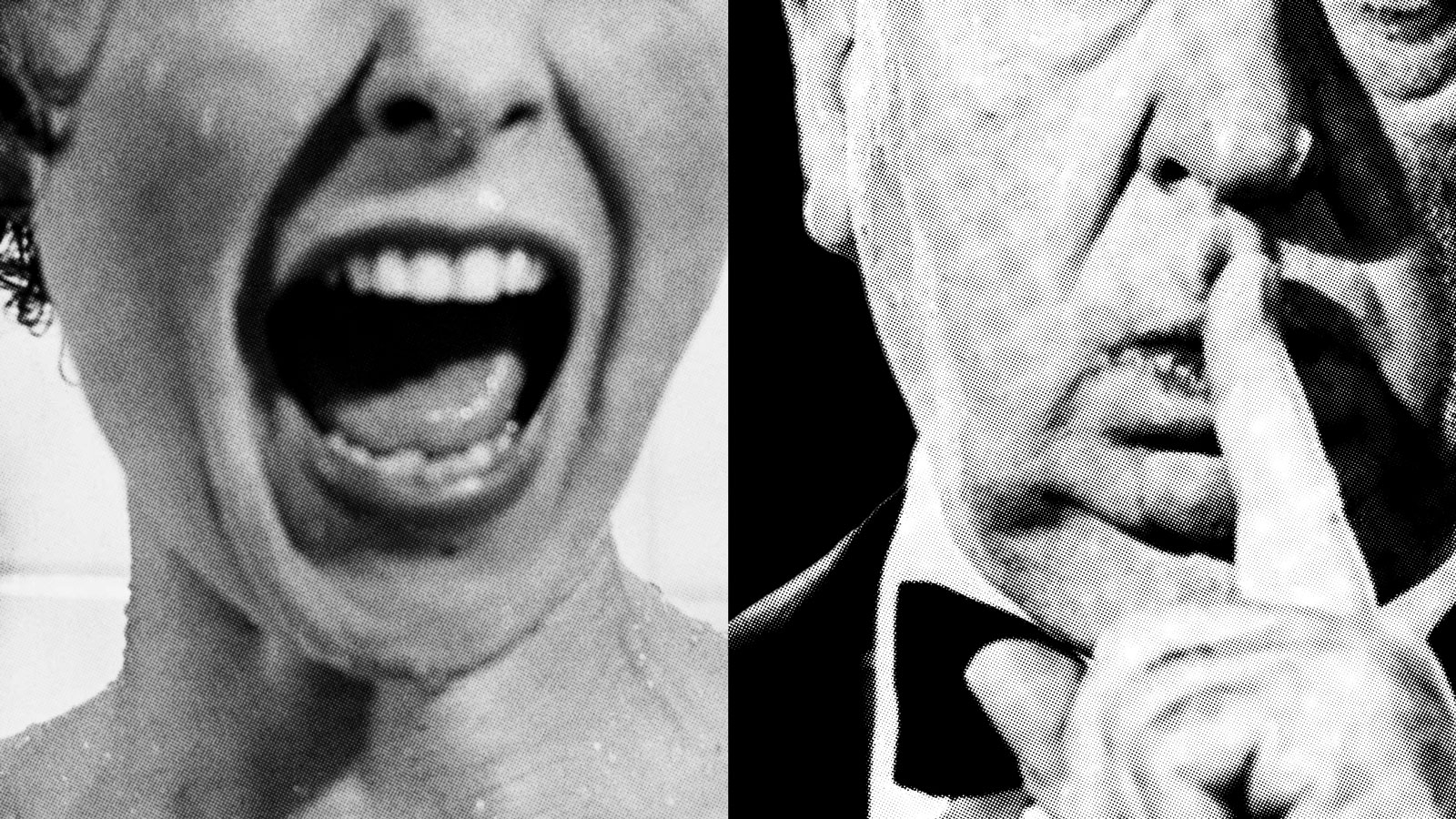

Sonically, Psycho is remembered above all for its infamous shower scene, in which heroine Marion Crane is stabbed to death by crazed motel owner Norman Bates. According to the production history, Hitchcock initially didn’t want to use music for the scene, believing it would be more effective if left completely silent. He changed his mind after hearing what composer Bernard Herrmann came up with: an all-string piece titled The Murder, whose screeching violins matched the movement of Bates’ knife while simultaneously evoking Crane’s icy screams. The impact of the shower scene — now one of the most iconic images in all of pop culture — taught Hitchcock that, while sound can never replace image, one can be used to reinforce the other.

On purity

The term “pure” can also be applied to other art forms. Pure music, sometimes called abstract or absolute music, refers to music that is not necessarily about anything and exists for its own sake. The same goes for pure poetry, which deals mainly with rhythm and sound. The term pure video games — games that emphasize design and player agency at the expense of storytelling — comes up especially frequently nowadays, perhaps because the medium is still young and in search of a unique identity.

As far as pure cinema is concerned, it’s important to note that Hitchcock’s theory on film is simply one of many. For every Alfred Hitchcock, there is another theorist who argues that cinema is at its best not when it restricts itself to shot and montage but when it fully embraces music, literature, and other art forms to form what opera conductor Richard Wagner called a Gesamtkunstwerk, or “total work of art.”

However, even if filmmakers don’t subscribe to the idea of pure cinema, studying its principles can still help them elevate their craft. Beyond sound, pure cinema is about being selective, removing redundancy, and creating films where even the smallest details — from the placement of the camera to the costumes of the actors — serve a purpose in relation to the bigger picture.