Can you change the mind of an anti-vaxxer? Yes, say researchers. Here’s how.

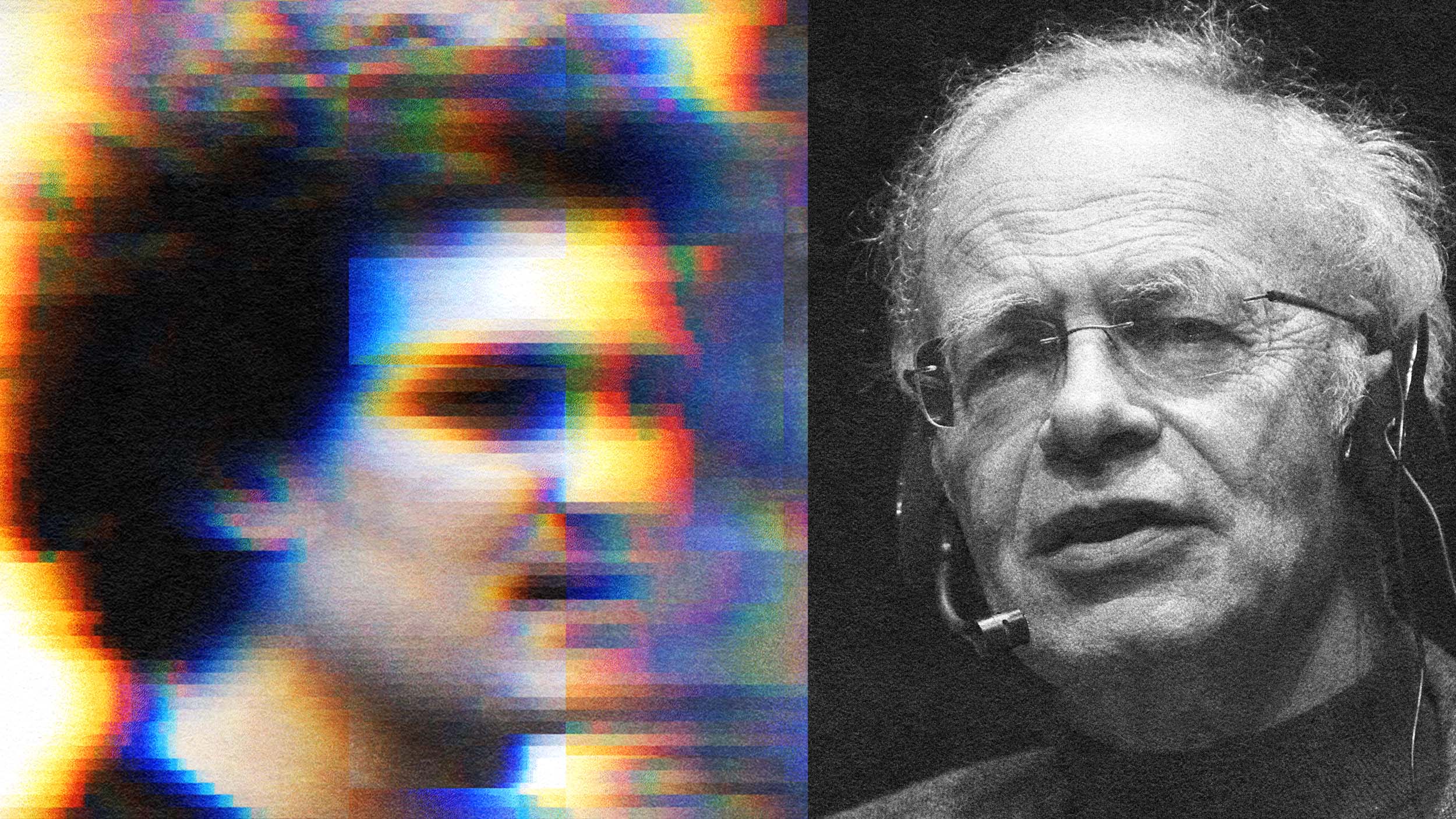

Photo credit: George Frey / Getty Images

- Talking to people who have experienced vaccine-preventable diseases changes minds.

- Seventy percent of Brigham Young University students shifted their vaccine-hesitant stance.

- This research arrives during a year in which 880 measles cases have been identified in America.

There is no greater teacher than experience — or the experience of others, it turns out. Educating the anti-vaxx population has proven to be challenging, yet a new intervention conducted by researchers at Brigham Young University appears to work: introduce anti-vaxxers to people who have suffered from vaccine-preventable diseases.

The study, published in the journal Vaccines, was conducted with college students in Provo, Utah, a city with the sixth-highest number of under-vaccinated kindergartners. Of the 574 student volunteers, 491 were pro-vaccine and 83 were vaccine-hesitant.

Half of these students interviewed someone who had suffered from a vaccine-preventable disease (such as polio); the control group interviewed people who had lived through autoimmune diseases. Simultaneously, some students were enrolled into classes featuring immune- and vaccine-related curriculum, while others received no vaccine training in the health class.

The following questions were asked before their interviews:

And these were the questions were asked to the interview subject:

Finally, the students were asked a longer set of questions after their research, including whether vaccines, treatment for autoimmune diseases, and depression medications are “more harmful than helpful”; if vaccines cause autism; how hearing about the vaccine-preventable disease changed their views on vaccines; and how much financial impact affected their thoughts on treatment. Finally, researchers wanted to know if the study changed their feelings on vaccines.

BYU associate professor of microbiology and molecular biology, Brian Poole, summates the findings:

“Vaccines are victims of their own success. They’re so effective that most people have no experience with vaccine preventable diseases. We need to reacquaint people with the dangers of those diseases.”

By the end of the study, around 70 percent of vaccine-hesitant students reassessed their position, even with no vaccine class training. Learning about the suffering of others shifted their perspective, as one student, who interviewed her grandmother (who had suffered from tuberculosis), put it:

“I dislike the idea of physical suffering, so hearing about someone getting a disease made the idea of getting a disease if I don’t get vaccinated seem more real.”

A full three-fourths of the vaccine-hesitant students increased their “vaccine attitude scores,” with half of them moving fully to the pro-vaccine side. While the educational curriculum was important, the biggest change occurred when students talked to those that had suffered from vaccine-preventable diseases.

The Journey of Your Child’s Vaccine

This research is especially important as this year’s measles outbreak has risen to 880 cases, with the largest number hitting Orthodox Jewish communities in New York. Undeterred, anti-vaxxer activists are comparing forced vaccinations to Nazi Germany, spreading blatantly false information to confused parents.

Yesterday, the New York Times editorial board called for the State of New York to end the religious exemption for vaccines. Exceptions should be made if the health of the child is endangered, as current law dictates. Considering 41 cases were diagnosed last week — 30 in New York alone — the board states this is not the time for legislation to be paused in the courts. Religious belief, they write, does not give anyone the right to infect other members of society.

With so much misinformation circulating since the infamous, discredited autism-vaccine study (though anti-vaccine activism existed before that day), the researchers at BYU might have hit upon an important antidote. As Poole concludes:

“If your goal is to affect people’s decisions about vaccines, this process works much better than trying to combat anti-vaccine information. It shows people that these diseases really are serious diseases, with painful and financial costs, and people need to take them seriously.”

—

Stay in touch with Derek on Twitter and Facebook.