World’s first malaria vaccine can save thousands of children lives

Mothers wait as their sick babies receive treatment for malaria at a hospital in M'banza Congo, Zaire province. Photo credit: USAID / Flickr

- Malaria, one of the world’s deadliest diseases, kills 435,000 people a year, most of them children in Sub-Saharan Africa.

- Three African countries are set to receive the world’s first malaria vaccine this week as part of a WHO pilot program.

- The vaccine has the potential to save the lives of hundreds of thousands of children worldwide.

The 20th century has seen some truly profound advances in human medicine. We now produce clean water and uncontaminated food at unprecedented levels. We’ve eradicated smallpox and rinderpest — the former having been one of history’s deadliest diseases, the latter having caused widespread, depopulating famine — and we’re close to eradicating deadly, debilitating diseases such as polio, yaws, and rabies.

But some medical leaps have been more elusive. One of the most devastating has been our inability to find a cure for malaria.

Malaria is among the world’s deadliest diseases. It kills 435,000 people worldwide every year, the vast majority in Sub-Saharan Africa. Ninety percent of all malaria-related deaths occur in Africa, and children under the age of five are its most likely victims. In fact, every tenth child death in 2016 was the result of malaria.

But that tragic paradigm may be changing soon. The World Health Organization has launched a pilot program for the world’s first malaria vaccine, a change that’s been three decades in the making.

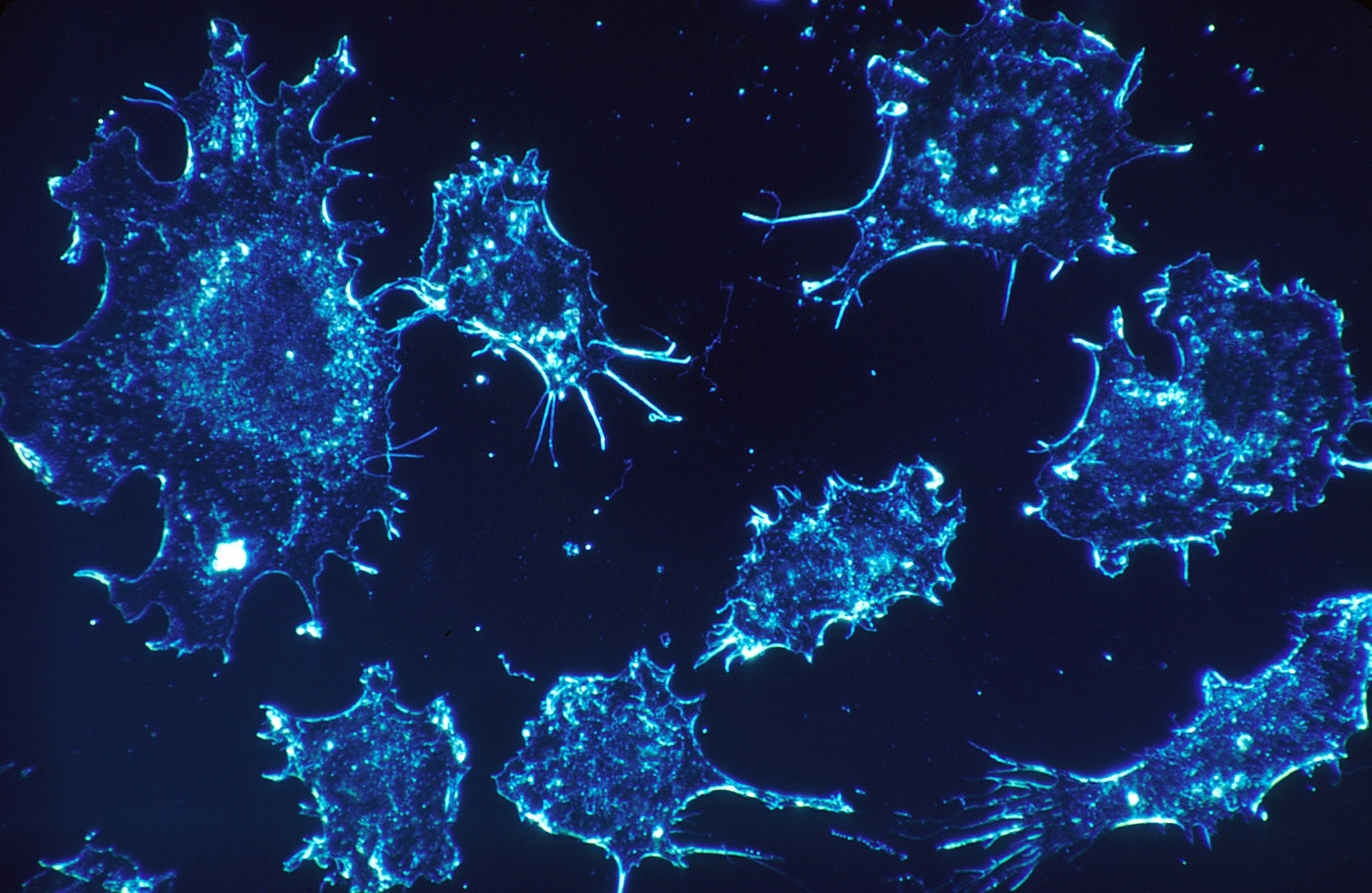

Image source: CDC / Wikimedia Commons

Countering the malaria epidemic

The malaria vaccine pilot program will launch in Malawi this week. In 2016, the country suffered 45 malaria-related deaths per 100,000 people. In the coming weeks, Ghana and Kenya will introduce the vaccine as well. In 2016, these countries suffered 69 and 11 deaths per 100,000 respectively.

The vaccine, called RTS,S, will be administered in a regimen of four doses. The first three will be given to children between five and nine months of age. The final dose will be provided around the children’s second birthday. The program aims to vaccinate around 360,000 children per year across the three countries. It will focus on areas with moderate-to-high malaria transmission rates in the hopes of maximizing the impact.

“Malaria is a constant threat in the African communities where this vaccine will be given. The poorest children suffer the most and are at highest risk of death,” Dr Matshidiso Moeti, WHO Regional Director for Africa, said in a statement. “We know the power of vaccines to prevent killer diseases and reach children, including those who may not have immediate access to the doctors, nurses and health facilities they need to save them when severe illness comes.”

WHO’s press statement notes that the pilot program is a global partnership. It has brought together a range of in-country and international partners to coordinate with the ministries of health in the three pilot countries. GSK, the vaccine’s developer and manufacturer, will donate 10 million doses.

“This is a day to celebrate as we begin to learn more about what this tool can do to change the trajectory of malaria through childhood vaccination,” Moeti added.

Difficulties in eradicating malaria

However, the vaccine is not a silver bullet aimed at ending the malaria epidemic. RTS,S does not have a 100 percent success rate, offering only partial protection. In clinical trials, it prevented approximately 4 in 10 malaria cases (3 in 10 for life-threatening malaria).

As such, WHO is presenting the vaccine as a “complementary malaria control tool.” The vaccine paired and supported by other preventative measures, including bed nets, indoor insecticides, and antimalarial treatments.

“It’s a difficult disease to deal with. The tools we have are modestly effective but drugs and insecticides wear out — after 10, 20 years mosquitoes become resistant. There’s a real concern that in 2020s, [cases] are going to jump back up again,” said Adrian Hill, a professor of human genetics and director of the Jenner Institute at the University of Oxford, told CNN.

Malaria has proven difficult to eradicate because of its nature. The disease is caused by a parasite of the genus Plasmodium. Its life cycle is split between a sexual stage in its mosquito hosts and an asexual stage in human hosts. When a mosquito bites an infected human, it contracts the disease from that person’s red blood cells.

When it bites another person, the mosquito transmits the disease to a new host. The infected patient develops a fever, chills, headaches, and other flu-like symptoms. If untreated, it can develop into severe malaria, where the symptoms can manifest into anemia, organ failure, and neurological abnormalities. Any mosquito that bites this person has the chance to then pass on the disease further.

The difficulty in preventing mosquito bites, the insect’s growing resistance to insecticides, and changes the parasite undergoes during its life cycle, all contribute the difficulties on controlling and containing malaria in the world’s poorest countries.

Graph showing the percentage of global malaria deaths per world region. Africa accounts for 90 percent of deaths resulting from the disease. (Source: Our World in Data)

Developing sustainable change

WHO’s Sustainable Development Goals are 17 directives comprising 169 targets. The ultimate aim is to advance peace and prosperity for all people.

The program’s third directive is to ensure health and well-being for all people of all ages. Among its targets are the end of the AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria epidemics by 2030 and the reduction of mortality for children under 5 to as few as 25 per 1,000 live births worldwide.

Despite the difficulties still ahead, any substantial reduction in malaria deaths is a welcome change and a significant step in achieving this goal.

Thanks to this vaccine, hundreds of thousands of children will likely avoid a crippling, painful death. Communities in some of the world’s poorest regions will be given a chance to better stabilize and grow. And the pilot may help scientist develop better strategies for future endeavors.

The vaccine’s development came at an auspicious moment, too. Malaria cases began to rise in 2017, after nearly two decades of decline.

“The malaria vaccine is an exciting innovation that complements the global health community’s efforts to end the malaria epidemic,” Lelio Marmora, executive director of Unitaid, said. “It is also a shining example of the kind of inter-agency coordination that we need. We look forward to learning how the vaccine can be integrated for greatest impact into our work.”