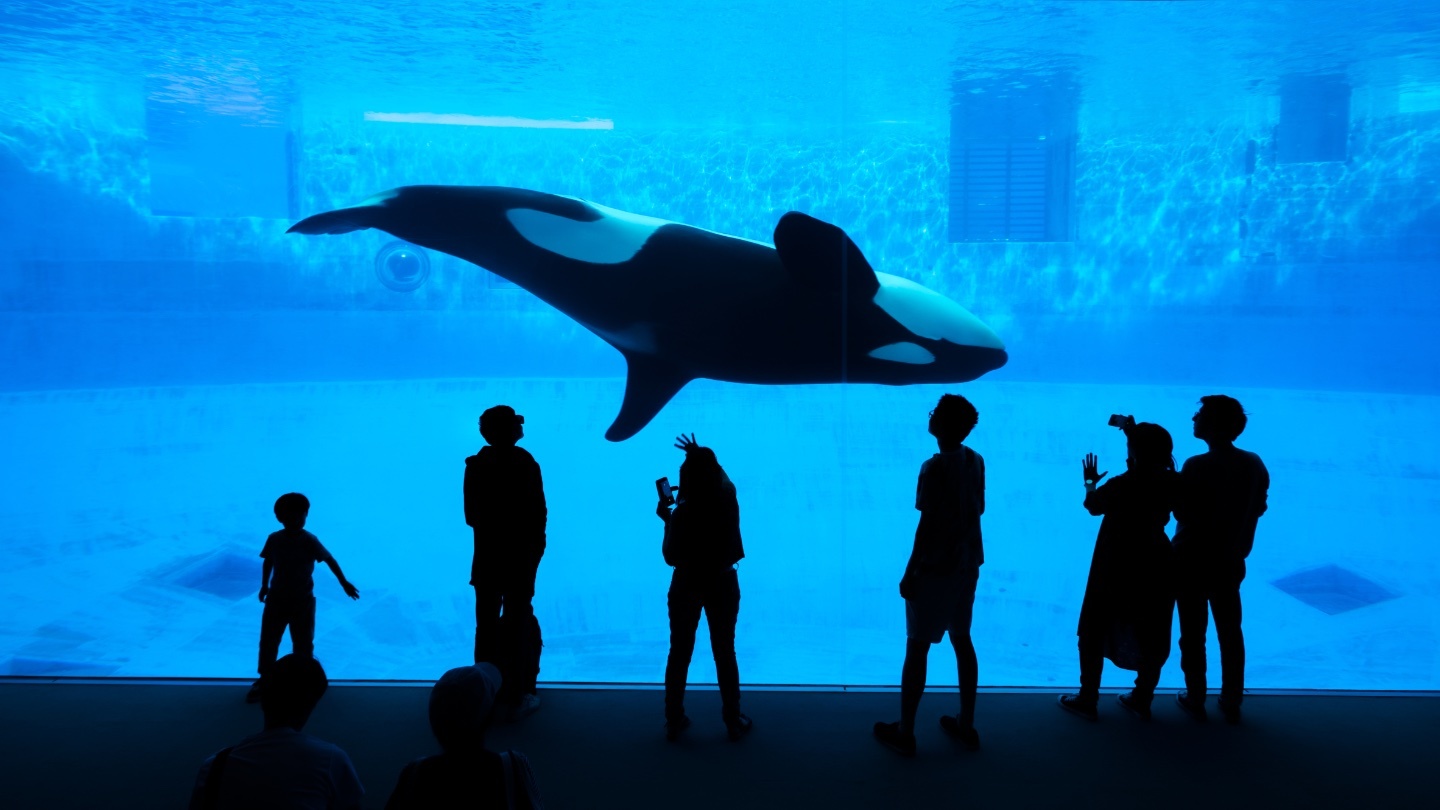

Whale earwax reveals 146 years of humanity’s impact

Photo credit: Miguel Medina

- It’s just been discovered that whale earwax contains a record of a whale’s sub-lethal stressors.

- It’s generally agreed that cortisol is a reliable indicator of a mammal’s response to stress.

- We now have a detailed 146-year impact study of human activity on whales.

Baleen whales (Mysticeti) have been subjected to human interference for a long time. The 14-member set, which includes humpbacks, minke whales and blue whales, has dealt with being hunted, increased boat traffic and fishing, noise, and pollution. It’s been difficult to ascertain the effect all this has had on individual whales, though, due to the challenges involved in collecting hormones and tracking changes over single whale’s lifetime. Baleens themselves can provide some information, but just for the last decade. However, a remarkable long-term record of a whale’s stress history has been discovered: the whale’s earwax plug.

According to comparative physiologist Stephen Trumble of Baylor University and his team of researchers, each plug contains a history of a whale’s sub-lethal stressors. Their study, just published in Nature Communications, reveals for the first time what our activities for the last 146 years have been like for leviathans.

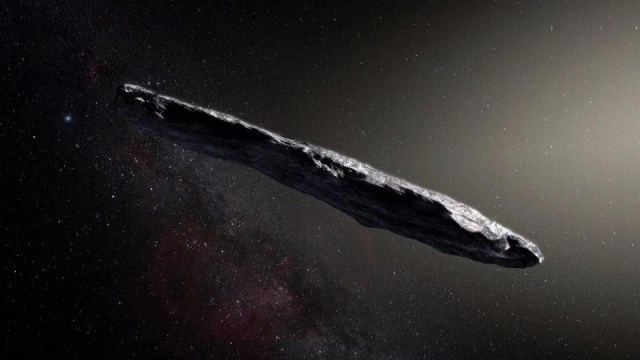

Black horizontal marks show six-month intervals

(Trumble, et al)

Gross, maybe. Incredible, for sure.

The baleen-whale earwax plug is large: up to a foot and a half long and two pounds in weight. Every six months — as shown above — a lipid/keratin-based layer is left behind. As with tree rings, these alternating light/dark bands allow researchers to mark the passage of time. Separating the layers requires precise, careful effort. But, Trumble tells National Geographic, “Being able to put together a picture of what stressors are involved and then the response of the whale — especially over lifetimes — is unprecedented.”

Museum curators have, apparently, been holding onto the plugs from dead specimens for hundreds of years, and these have provided Trumble a compelling glimpse into the lives of long-dead individuals.

The cortisol levels for the earwax specimen above

(Trumble, et al)

A story in cortisol

It’s generally agreed that cortisol, a hormone produced in response to stress by the hypothalamic, pituitary, and adrenal glands, makes a reliable indicator of a mammal’s response to stress. More stress results in higher levels of cortisol. In other animals, scientists can track the hormone in a variety of bodily media, including blood, feces, and urine.

(Trumble, et al)

Whaling, WW II, and climate change

One startling discovery is how closely cortisol levels mirrored the era of whaling from the late 19th century right up until the Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972, when the practice was dramatically reduced. Looking at cortisol levels in humpbacks, fin whales, and blue whale, cortisol levels dropped immediately in response to whaling cutbacks. “The result that surprised us was the correlation itself,” Trumble said.

From 1935 to 1945 there was a clear spike in stress, which makes sense, given the prevalence of military activity then. Trumble: “We suspect this increase in cortisol during World War II is probably a result of noise from planes, bombs, ships, et cetera.”

Trumble also found a concerning correlation between the rise of ocean temperatures and whales’ cortisol levels, most obviously since 1990. The obvious implication is that climate change is proving to be a serious stressor for the animals, though Trumble hopes to assess the connection more carefully in the future, using a larger sample than the six earwax plugs in which the correlation was detected.