This private space mission aims to discover alien life on Venus

- Venus Life Finder is a privately funded, three-part mission that aims to send spacecraft to Venus and collect atmospheric samples, which could indicate the presence of life.

- The first mission of the project could occur as soon as 2023.

- Even if no life is found on Venus, the scientific community will still obtain valuable data about the planet.

In recent years, we’ve become accustomed to commercial space companies taking over jobs that NASA or the European Space Agency used to do. Now comes another exciting milestone: a privately funded mission that aims to find extraterrestrial life in our own Solar System. The project, headed by MIT scientists and engineers from Rocket Lab, is called Venus Life Finder, and initial funding for the concept study was provided by Breakthrough Initiatives.

The project is divided into three broad missions. The first is scheduled for May 2023 and financing is largely secured, with Rocket Lab providing both the launch and the spacecraft, using the company’s Electron rocket and small Photon spacecraft, whose modest 1-kilogram science payload is partially funded by MIT alumni.

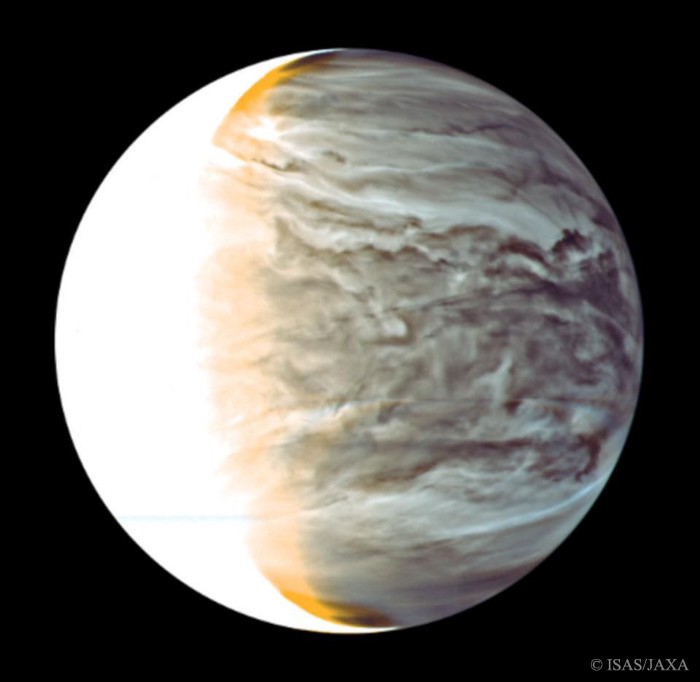

The mission aims to send a small atmospheric probe to analyze cloud droplets in the lower Venusian atmosphere, which has long been hypothesized to harbor microbial life. An instrument on the probe would shine ultraviolet light on the droplets, known as Mode 3 particles. The probe would spend only about five minutes collecting data, but that should be sufficient: If the droplets contain organic molecules, they should fluoresce when exposed to the UV light. The presence of organic molecules would strongly hint at the presence of life but wouldn’t prove it.

The timing of this first launch in May 2023 is certainly ambitious, but even if it slips to the backup date of January 2025, the development time would still be much faster than your typical NASA mission.

The second mission would drop an instrumented balloon into the Venusian clouds to float at an altitude of about 50 kilometers where it would analyze the potential habitability of that region while searching for further evidence of life. The third and final mission would collect and return to Earth a 1-liter sample of atmospheric gas, along with several grams of cloud particles. Lab analysis should be able to show conclusively whether there is life in the Venusian atmosphere.

Financing of the follow-up missions is not yet secured, and it may depend on the success of the initial atmospheric probe mission. The possibility of finding life in the Venusian clouds, of course, remains speculative. It should be noted that the mission was devised by many of the same authors who reported detecting phosphine in the Venus atmosphere back in 2020. That controversial claim reinvigorated the debate over whether life is possible in the Venusian clouds.

This is exactly how science is supposed to work: A hypothesis is advanced, and after some supporting evidence is found, efforts are undertaken to put that hypothesis to the test. In this case, it requires sending multiple spacecraft to Venus. It’s quite impressive that the mission team, led by Sara Seager from MIT, was able to secure private funding rather than wait many years for public funding of what many scientists would consider a debatable hypothesis.

I’d like to see more such bold initiatives. If there’s a reasonable chance of discovering extraterrestrial life, why not take the risk and go for it? Even if no life is found at Venus, the scientific community will still obtain valuable data.

Venusian mysteries

Venus is enjoying something of a renaissance these days. Two NASA missions (VERITAS and DAVINCI) and one ESA mission (EnVision) are already in the works. Unfortunately, these won’t arrive until the late 2020s and early 2030s, respectively. Don’t get me wrong: All three will make significant contributions, most importantly in determining the chemical environment at Venus and gaining insight into the planet’s history. But the privately funded mission will likely occur much, much faster (at least part one will be), and will investigate the possibility of Venusian life directly.

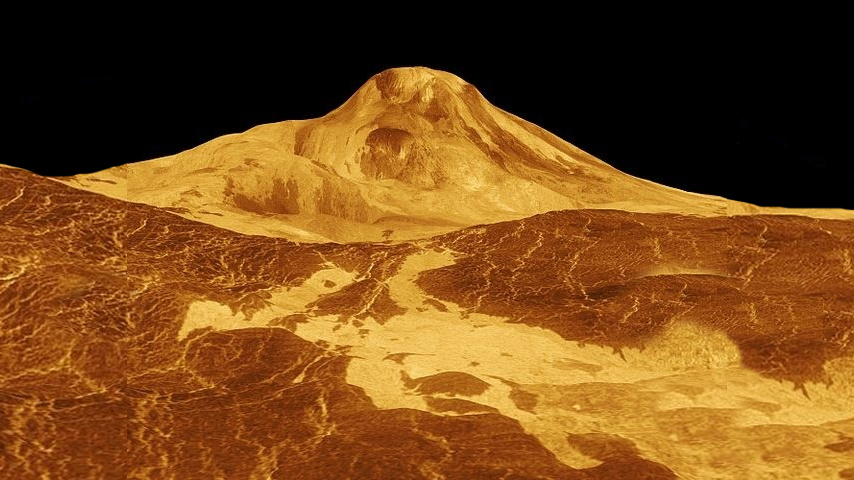

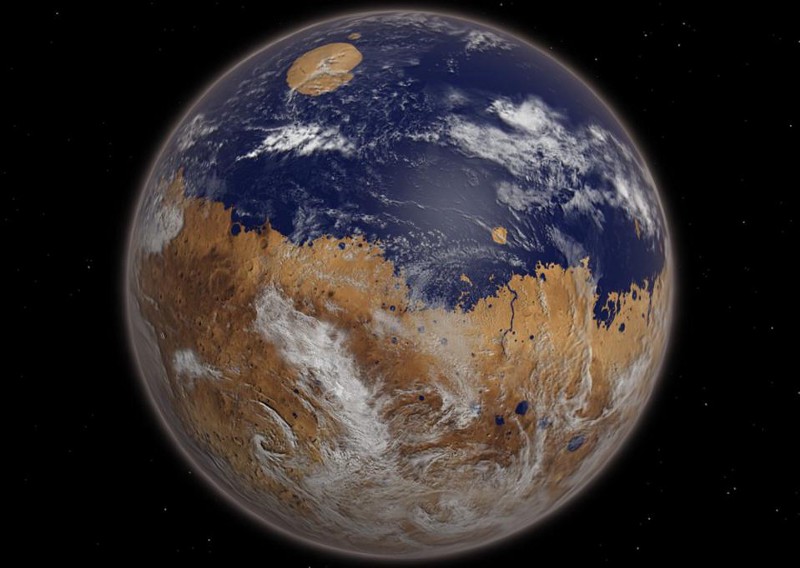

What are the chances of finding it? The argument goes something like this: Venus might have had early oceans similar to Earth’s where life developed independently or thrived after being transported via asteroids from Earth. However, being closer to the Sun and lacking a global recycling mechanism (such as plate tectonics on Earth), Venus underwent a runaway greenhouse effect.

As a result, any early life on the planet’s surface would have since gone extinct. Some organisms, however, could have retreated into the cloud layer, where environmental conditions are fairly benign: Earthlike atmospheric pressure, temperatures between 35 and 80oC, potential nutrients, and even a small amount of water.

Now the counter-arguments. It’s not actually certain that Venus used to be a water world. In fact, the planet’s natural history is still something of a mystery (here is where the NASA and ESA missions will really help). Even if life did once arise, there are major obstacles to it surviving today in the clouds. The lower cloud layer is high in sulfuric acid, with levels many times worse than what any acid-loving microbe on Earth could stand.

Nevertheless, William Bains and his co-authors in a recent paper present a possible way around this problem: They point to certain organisms on Earth that secrete ammonia to neutralize their immediate acidic environment. If putative Venusian microbes use a similar mechanism, they could conceivably raise the pH-value in the cloud droplets to about 1—still very low by Earth standards, but high enough for some terrestrial microbes to survive. This is especially intriguing, since past probes have detected ammonia on Venus.

The low water abundance might be an even bigger problem for potential life in the Venusian clouds, especially since the little water that does exist is mostly bound to sulfuric acid, and therefore might not be accessible to microbes. We see the same effect in honey. Despite the high nutritional value of honey, it doesn´t spoil because microbes don’t have access to enough water. One way around this problem at Venus would be the existence of microenvironments that contain more water than the atmosphere in general. It would require several orders of magnitude more, however.

Other challenges include the microbes’ aerial “lifestyle,” which probably means a lack of the trace metals used in many biochemical processes. Temperature, though, is unlikely to be a problem, despite the Venusian surface being hot as an oven. Up in the clouds, things are much cooler.

Given our current knowledge, these challenges are largely theoretical. Most of our knowledge about Venus is based on modeling, and we desperately need direct measurements. It seems clear, though, that no Earth organism could thrive under current environmental conditions on Venus, even in the clouds. Any life that grew up on this alien world would need biochemical adaptations unknown on our planet.

That’s not unthinkable, however. Highly acidic environments are rare on Earth, so there was never much natural selection pressure to adapt to such conditions. We already know that rich and complex sets of organic molecules can be stable within concentrated sulfuric acid. Perhaps we just need to keep an open mind and remember the famous line from Jurassic Park: “Life finds a way.” Sending the Venus Life Finder is a great way to discover whether that’s also true on other planets.