Geneticists reverse engineer DNA of the first black Icelander, who left no remains

It’s no wonder Iceland is a country obsessed by genealogy.

The majority of its 330,000 inhabitants descend from a small group of Vikings and Celts who settled some 1,100 years ago, and immigration to the island country has been rare ever since. Icelanders keep exceptional genealogical records on almost every single citizen, a longstanding practice done partly out of ancestral reverence, but also to avoid the very real possibility of bedding down with a not-too-distant relative.

Case in point: In 2013, a group of engineering students at the University of Iceland released an incest prevention app that lets users tap their phones together to see if they share a common ancestor. Its slogan? “Bump in the app before you bump in bed.”

The country’s genealogical records can be found in the Islendingabok, “the book of Icelanders,” which contains detailed genealogical information for about 95 percent of Icelanders who have lived over the past three centuries. It’s this database and the country’s unique demographic history that have made Iceland ideal for genetics research.

deCODE, an Icelandic genetics firm, has for years been using the genealogical records to study how genetic mutations can affect people’s chances of having everything from cancer to blond hair. Most recently, the firm used the records, along with well-known DNA markers, to reconstruct a substantial part of the genome of an 18th-century man.

“To our knowledge, this study demonstrates the first use of genotype data from contemporary individuals, along with information about their genealogical relationships, to reconstruct a sizeable portion of the genome from a single ancestor born more than 200 years ago,” the team wrote in an article published in Nature.

The reconstructed genome belonged to Hans Jonatan, a mixed-race man who escaped slavery in 1802 by sailing to Iceland where he was accepted “with open arms,” as Kári Stefánsson of deCODE toldNew Scientist. Before his death in 1827, Jonatan married an Icelandic woman and raised two children, marking the introduction of African DNA into the country’s gene pool.

“There was no African ancestry in Iceland, apart from Hans Jonatan, prior to around 1920,” Stefánsson toldNew Scientist.

Lúðvík Lúðvíksson, grandchild of Hans Jonatan. Credit: Helga Tomasdottir

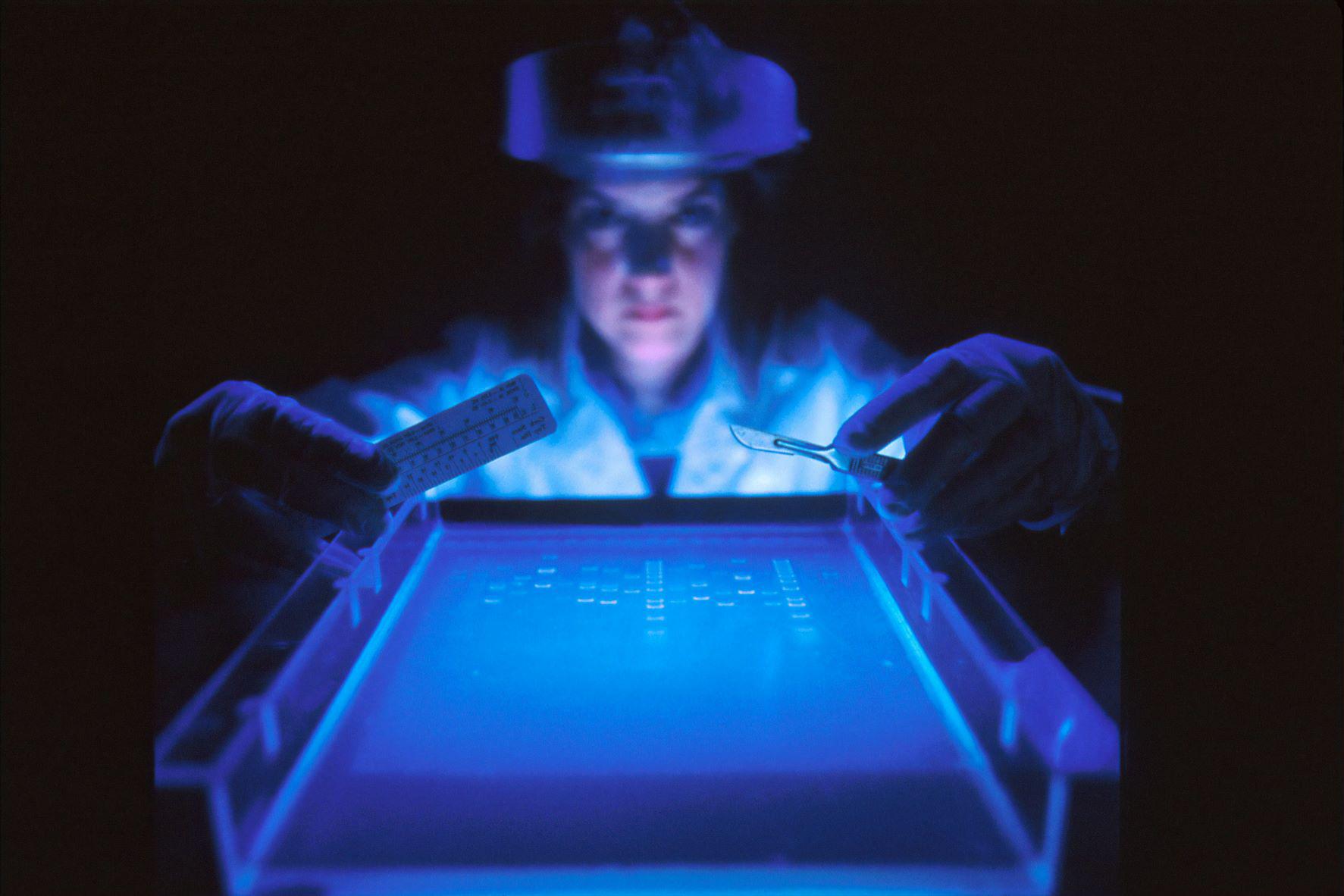

To reconstruct part of Jonatan’s genome sequence, the team identified 182 of his living descendants in Iceland and searched their genetic code for well-known African DNA markers, under the assumption that these bits of DNA could have only been inherited from Jonatan. The researchers found in the descendants 593 fragments of African DNA that they used to re-create 38 percent of Jonatan’s mother’s genome, which represents 19 percent of his own. They also were able to determine that his mother’s family likely originated from the African countries of Benin, Cameroon, or Nigeria.

Diagram representing Jonatan’s descendants.

“Ancestor genome reconstruction of this kind can be viewed as a virtual ancient DNA study, whereby genotype information is retrieved from a long-dead individual without the need for DNA samples from physical remains,” the team wrote.

There are a few of proposals of what “virtual ancient DNA” might be used for in the future.

“It’s the sort of study that could, for instance, be used to recover genomes of explorers who had interbred with isolated native communities,” Robin Allaby, a biologist at the University of Warwick, told Futurism.

Agnar Helgason of deCODE said in the same piece that scientists could use the process to reconstruct the genome of “any historic figure born after 1500 who has known descendants” —noting the year 1500 due to lack of genealogical information and because the expected genetic contribution of an ancestor to a single descendant is very small after 10 generations.

The team also suggested genome reconstruction could be used by medical researchers “in cases where valuable phenotype data is available for ancestors who can no longer be sampled for DNA and directly genotyped.”

In any case, the team wrote, the study highlights the ongoing genetic story “of a resourceful refugee from the Danish transatlantic slave trade, who was able to prosper in a culturally homogeneous and insular community of early-nineteenth-century Icelanders.”