Life in the Universe: It’s either everywhere or nowhere

- The Fermi paradox highlights the contradiction between the expected commonality of advanced technological life in the Universe and the actual scarcity of evidence for alien life.

- Two possible solutions to the paradox include: (1) Advanced extraterrestrial intelligent life (ETI) is either extremely rare or non-existent in our galaxy; (2) these civilizations are deliberately hiding from us.

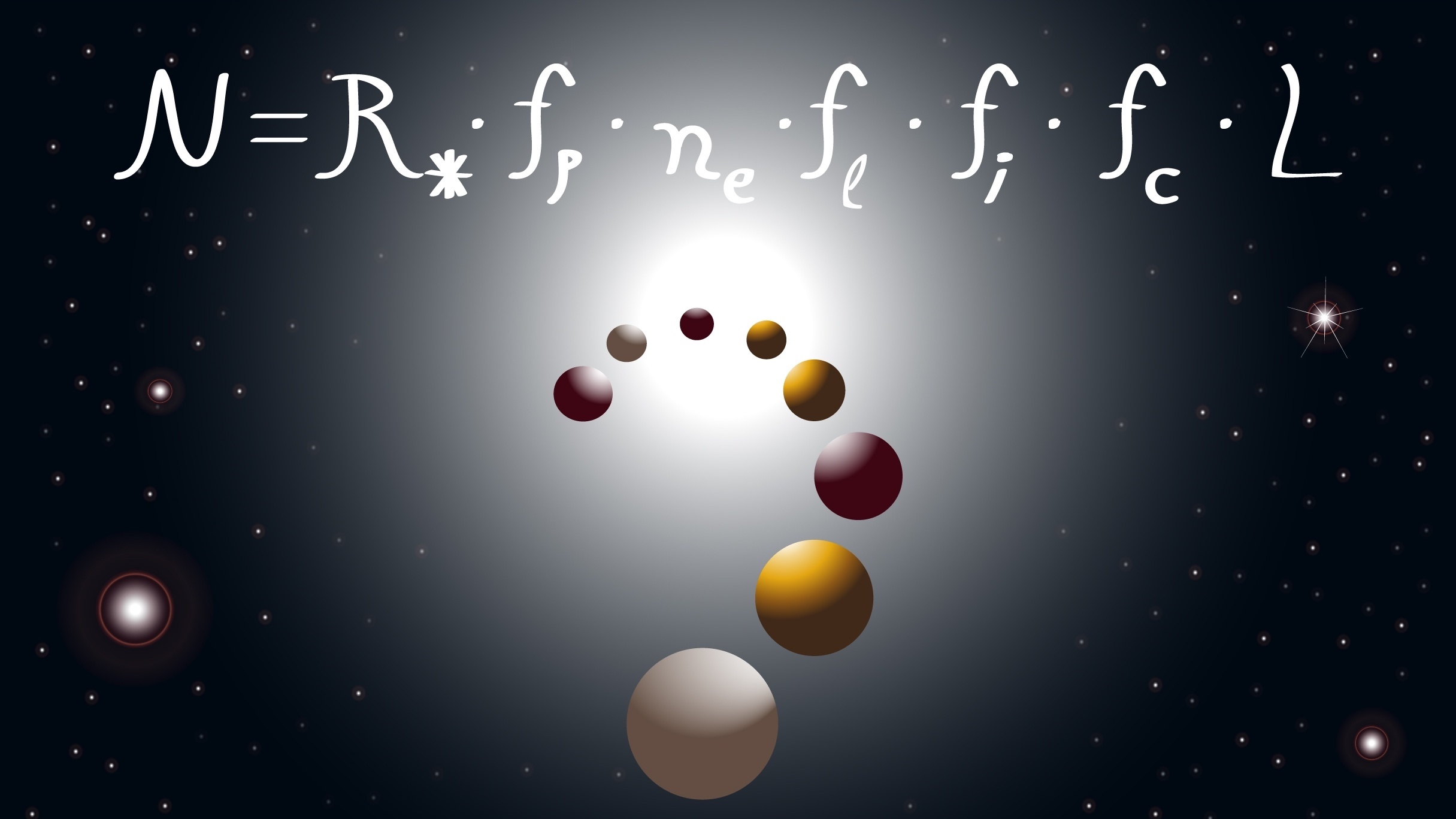

- As astronomers rapidly discover new exoplanets, the potential for identifying technosignatures on some of these planets offers a promising avenue to address the Fermi paradox and possibly uncover evidence of alien societies. For now, however, it’s only possible to speculate on solutions to the paradox.

My colleague Ian Crawford and I recently made a bet — a little bet with potentially big consequences.

In a paper recently published in Nature Astronomy, Ian — a planetary scientist and astrobiologist at the University of London — discussed possible solutions to the Fermi paradox, also commonly referred to as the “Great Silence.” This refers to the mismatch between the widely held expectation that advanced technological life should be common in the Universe and the apparent lack of evidence to support that belief. The discovery in this century of thousands of planets beyond our Solar System, along with recent interest by NASA and others in investigating Unidentified Aerial Phenomena (UAP), make a re-analysis of the Fermi paradox timely.

Our conclusion is that advanced extraterrestrial intelligent life (ETI) is either (1) extremely rare or non-existent in our galaxy or (2) these civilizations are deliberately hiding from us. No other possibility seems very likely. While Ian tends to favor the first explanation, I lean toward the second one. We settled on a wager, a bottle of whiskey, on whether convincing evidence for technological life elsewhere in the Universe will be found within the next 15 years.

What makes us conclude that there are only two likely answers to the Fermi paradox? We started by grouping all previously suggested solutions into categories. Some are based on the view that interstellar travel is unlikely or impossible, an argument that seems easy to dismiss. Even with spaceship velocities as low as tens of kilometers per second — speeds already attained by our “primitive” Pioneer, Voyager, and New Horizons spacecraft — it should be possible for aliens, whether biological or artificial, to reach nearby stars if they really wanted to, even if it takes millions of years.

Then there are what might be termed “sociological” solutions. Maybe extraterrestrials always destroy themselves before they master interstellar travel. Or maybe they all opt to stay home rather than venture out into space. (If that’s true, we’re now arriving at the point in our own evolution where we might detect technosignatures from these stay-at-home societies via remote sensing.) Amri Wandel at The Hebrew University of Jerusalem has made the intriguing suggestion that non-technological life is so common across the galaxy that ETIs only bother to visit planets with similarly advanced technology. But that certainly wouldn’t apply to us on Earth — we’d be excited to visit any planet with life on it, advanced or not. Besides, these kinds of behaviors only plausibly resolve Fermi’s paradox if they apply to every civilization in the Milky Way. And that seems unlikely given the huge number of civilizations that may have arisen over our galaxy’s 13-billion-year history.

The “Great Filter”

Related to these sociological explanations is the idea of a “Great Filter” — an evolutionary hurdle that most life forms in the galaxy never or hardly ever manage to survive. It may happen right at the point when life originates, and for some reason, we made it through. Or maybe, ironically, it’s the development of technology itself that spells doom. Many other intelligent species have arisen on our own planet, from parrots to octopuses to dolphins, and many of these have been around much longer than Homo sapiens. But none of them have developed nuclear weapons or other means of mass destruction. Is there perhaps a key evolutionary trait, perhaps related to human language or our specific type of culture or our tribalistic nature, that contains the seeds of our own destruction? Perhaps there are several Great Filters at different stages of evolution. Maybe the worst ones lay ahead of us (the scariest possibility).

Of course, if ETIs are extremely rare in the galaxy, there is no paradox. The reason we don´t see them is because they aren’t there. On Earth, it took about four billion years — most of our planet’s lifetime — to advance from simple microbial life to advanced technological life. And as far as we know, it has only happened here once.

The “zoo hypothesis”

The other possibility, however—the one I’ve bet a bottle of whiskey on—is that the aliens are here. They just don’t want us to know it. Following up on a 1973 proposal by John Ball, this “zoo hypothesis” holds that Earth is effectively a fenced-off game preserve, with extraterrestrial visitors not allowed to interfere. The idea was anticipated in Olaf Stapledon´s 1937 science-fiction epic Star Maker and was implicit in Star Trek’s “Prime Directive” in the 1960s.

It seems reasonable that any ETI with the technical ability to cross interstellar space could remain hidden from us if they choose to. One problem with this hypothesis, though, is that all such visitors would have to agree not to enter the zoo, at least for some time, perhaps until we reach some stage of advanced technology. It could be that some early galactic civilizations established rules governing non-interference for subsequent alien visitors to follow. Such a policy might be hard to enforce, however, and it’s tempting to speculate that a small fraction of reported UAP sightings are due to interstellar visitors not playing by the rules. Maybe the “zookeepers” mean to initiate contact gradually, depending on humanity’s stage of technological evolution. All we can do right now is guess, unfortunately.

To those who consider all of this idle speculation, here’s a challenge: How would you reconcile the Copernican principle — that humans don´t occupy a privileged position in the cosmos — with the idea that we really are the only advanced civilization in the Universe (in which case, consider the enormous responsibility weighing on our species!).

If ETIs are at least somewhat common, the only other way out of Fermi’s famous dilemma is the zoo hypothesis. And the good news is that, given our current rate of technological progress, it will be increasingly hard for the aliens to hide from us. We’re now discovering their planets at a rapid clip, and soon we may be able to detect their technosignatures remotely. I just hope it happens within 15 years. I have a bottle of whiskey riding on it. And more importantly, both of us, Ian and I, simply want to know.