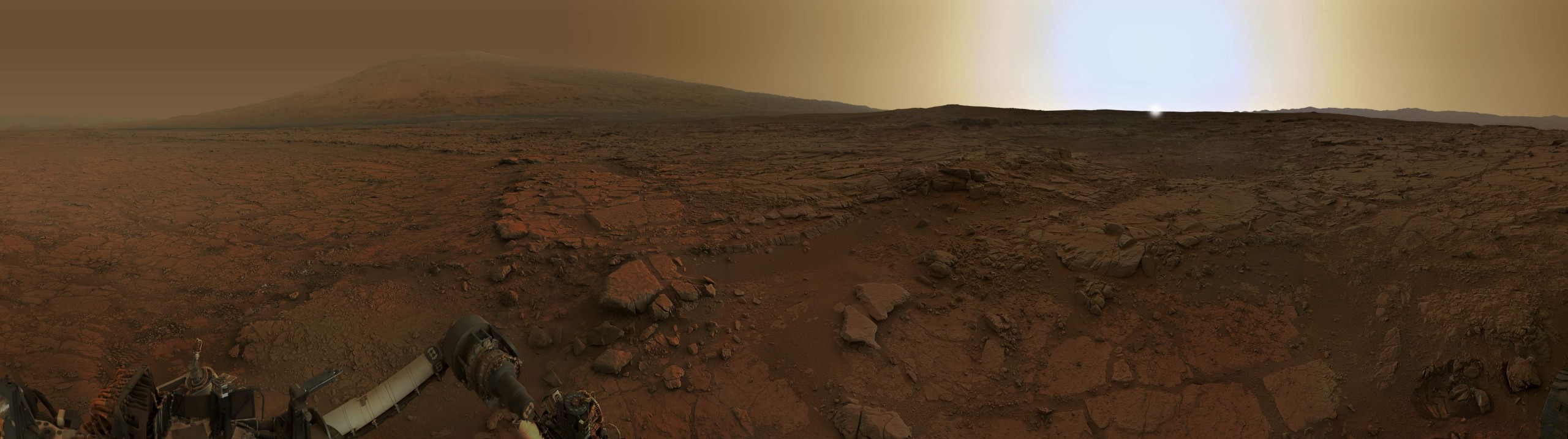

NASA’s curiosity rover finds remnants of a lost oasis on Mars

Image source: NASA

- Curiosity is exploring an exposed cross-section of Mars’ early history within the unusual Gale Crater.

- Intriguing salt deposits indicate briny bodies of water appearing and disappearing over time.

- Curiosity is digging through Mar’s past in search of environments that could have supported microscopic life.

Gale Crater on Mars doesn’t look quite like you’d expect. It is a giant ring produced by an impact some 3.5 billion years ago, but it’s got a mountain in the middle, dubbed Mt. Sharp after geologist Robert P. Sharp. Yet that’s not what’s most interesting to scientists. Mars orbiters have detected signals suggesting a perplexing mix of sediments in the crater, indicators of a complicated history. NASA landed the Curiosity rover there in 2012, and for the last seven years the intrepid robot been rolling from place to place on its six wheels across the 100-mile-wide basin, studying the evidence up close.

On October 7, NASA Curiosity scientists published a paper in Nature Geoscience in which they present strong evidence of a lengthy cycle of oasis-like environments appearing and disappearing at the foot of Mt. Sharp during Mars’ Hesperian period between 3.3 and 3.7 billion years ago.

The complicated Gale Crater puzzle

From satellites orbiting Mars, scientists have detected sedimentary signifiers of very different climatic eras all jumbled together. On one hand, flat clay layers on the floor of the crater likely formed when the area was wet, having been fed perhaps from underneath and/or by streams flowing over the sides of the crater. Above those flat layers are angled sulfate layers that likely formed during much hotter times. Above it all is the Geddis Valles Channel that may be the remnant of a once-rushing river. What makes the Gale Crater so attractive as a research site is that a good deal of these different sediments are now exposed.

Scientists believe that sediments carried by wind and water were deposited in Gale Crater in layers, only to harden and eventually be carved away by winds. This has left a compelling cross-section of sorts of Mars’ history since the impact, splayed across a slope that’s gradual enough for Curiosity to methodically pick its way up on its six wheels. From the bottom of the crater to the top, the rover photographs, samples, and analyzes materials it finds.

Since the rover was gently landed on the Martian surface in 2012 from a “sky crane,” scientists have already pieced together a plausible rough sequence of events leading to its current appearance, a sequence awarded a further degree of detail by the new research.

(Tap or click for interactive version.)

Image source: NASA

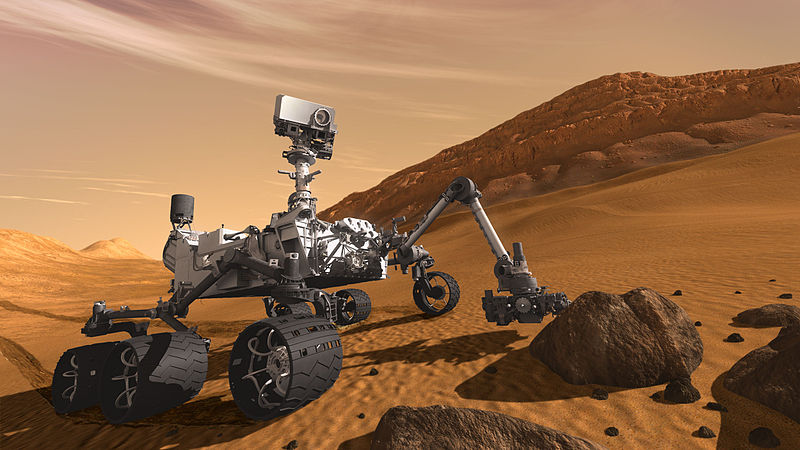

Tools of the trade

Says the study’s lead author William Rapin of Caltech, “We went to Gale Crater because it preserves this unique record of a changing Mars. Understanding when and how the planet’s climate started evolving is a piece of another puzzle: When and how long was Mars capable of supporting microbial life at the surface?” NASA views the spacecraft as marking the transition between the agency’s “Follow the Water” and “Seek Signs of Life” themes.

The car-sized Curiosity is equipped with a versatile set of instruments for its sleuthing. It would weigh in at 1,982 lbs on Earth, though it’s just a svelte 743 lbs on Mars. Onboard are cameras, spectrometers, radiation detectors, and atmospheric sensors. While all of the gear has an important role to play, perhaps the most relatable is Curiosity’s MAHLI, or “Mars Hand Lens Imager,” described as having a purpose similar to “the magnifying hand lens that geologists usually carry with them into the field.” NASA has a great interactive page showing how Curiosity gets around.

Image source: NASA

Sutton Island and Old Soaker

Many Martian features have been given names since we’ve been orbiting and visiting the planet, as you can see in a map showing Curiousity’s current location below.

In 2017, Curiosity visited a 500-foot-tall pile of sedimentary rocks dubbed “Sutton Island.” Prior to that, an examination of mud cracks in the crater basin — AKA Old Soaker — had led them to suspicions that there were alternating periods of wetness and dryness. The nature of the salt recently found on Sutton Island now suggests that those intermittent bodies of water were briny.

Normally, dried-up lakes leave behind pure table-salt-like crystals, though that’s not the case with Sutton Island. The crystals there are mineral salts, and contain sediments that suggest crystallization occurred when the area was still wet, and possibly took place underneath shallow ponds of briny water.

Researchers suspect that the Gale-Crater basin may have long ago been similar to today’s high-altitude Altiplano plateau in South America, which is fed by streams and rivers running down from mountains. Says Rapin, “During drier periods, the Altiplano lakes become shallower, and some can dry out completely. The fact that they’re vegetation-free even makes them look a little like Mars.”

Another clue is that traveling up Mt. Sharp — and thus forward through Martian time — the flat layers typically left by sediments settling in water are falling behind, replaced by angled layers suggesting the deposition of materials from flowing water or wind. The mission’s Chris Fedo of says, “Finding inclined layers represents a major change, where the landscape isn’t completely underwater anymore.” Up the rise lie more tilted layers, suggesting a gradual progression toward the dryness we see today on Mars.

Since the basin of the crater reveals only Mars’ geology from the time of the impact, it’s reasonable to assume that underneath could be found evidence of more wet/dry transitions. Does the exposed clay merely represent a stage in a sequence already in progress before Gale Crater existed? Fedo concludes, “We can’t say whether we’re seeing wind or river deposits yet in the clay-bearing unit, but we’re comfortable saying is it’s definitely not the same thing as what came before or what lies ahead.”