Who Cares About Fiction?

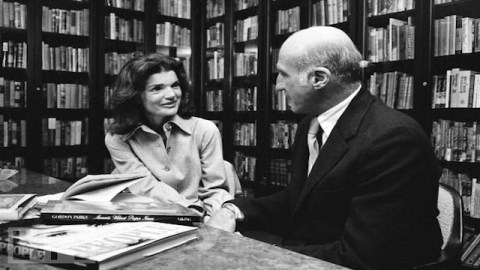

Because whatever becomes of the allocation of electronic rights, the death of chain stores, or (even) the recurring flirtations of this novelist or that poet with risky new forms, we can still argue this: the place fiction holds in our lives remains; it is central. We might lose this argument, but our belief that it is worth having is what matters. In caring, we ally ourselves with something—less than a cause, more than nothing. In this past week of national mourning, the literary world suffered loss, too. Thomas Guinzburg will be remembered.

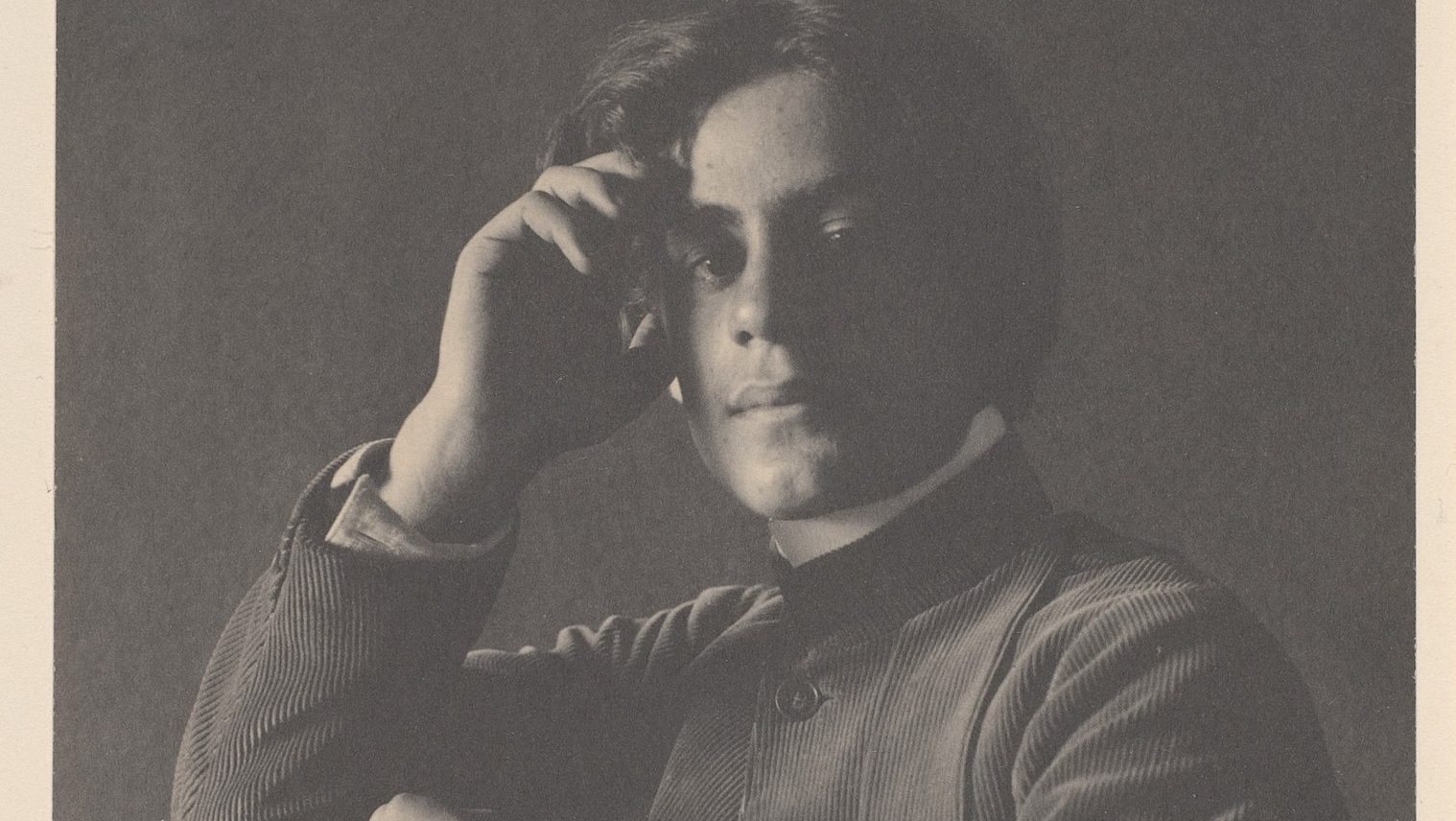

Guinzburg was a founding editor of The Paris Review. You can read about him via the Times obit here, or the via a blog post on the Review’swebsite here. His love for literature and his pride in the Review’s history matched an adamancy on fiction’s relevance to Americans’ lives. John Steinbeck was best man at his first wedding.

Recently, the Review’s Editor, Loren Stein, told the FT that “you can be as smart and as stylish and as sophisticated and as cosmopolitan in poetry and fiction as you can be in non-fiction, and the corollary of that is that you don’t have to be polite about it, you don’t have to be pious about it.”

Neither polite nor pious: this might serve as a description of many twentieth-century American writers we love, writers celebrated and published first in the pages of “little magazines.” In 2003, shortly after the death of George Plimpton, the poet Billy Collins spoke at the Review’s annual Revel. He read his poem, “On Turning Ten.” He described the experience of coming to the Review’s offices for the first time, and of learning about the world of the magazine. It was a seemingly still (yet never not dynamic) center of the literary universe. Collins’s poem is wry and beautiful.

On fiction, Joan Didion said it best in The White Album: “We tell ourselves stories in order to live.

The princess is caged in the consulate. The man with the candy will lead the children into the sea.

The naked woman on the ledge outside the window on the sixteenth floor is a victim of accidie, or the naked woman is an exhibitionist, and it would be ‘interesting’ to know which. We tell ourselves that it makes some difference whether the naked woman is about to commit a mortal sin or is about to register a political protest or is about to be, the Aristophanic view, snatched back to the human condition by the fireman in priest’s clothing just visible in the window behind her, the one smiling at the telephoto lens. We look for the sermon in the suicide, for the social or moral lesson in the murder of five. We interpret what we see, select the most workable of multiple choices. We live entirely, especially if we are writers, by the imposition of a narrative line upon disparate images, by the ‘ideas’ with which we have learned to freeze the shifting phantasmagoria which is our actual experience.

Thomas Guinzburg never took himself too seriously; he understood the Aristophanic view. And he understood the power of ideas. And of words. We will miss him.