While Senate Introduces Climate Bill, Author Ian McEwan Introduces Climate Fiction

John Kerry and Barbara Boxer’s new Clean Energy Jobs and American Power Act is being trumpeted into the Senate this week. The act, stronger than the bill passed by the Congress in June (ACES), could create up to 1.9 million new jobs, make America energy independent, and combat climate change. Well worth your while, in other words, to take a minute out of your day to send your Senators a letter via the League of Conservation Voters, and ask them to support the act.

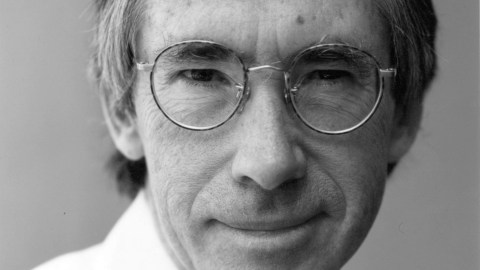

Meanwhile, in more understated news, a London novelist far away and across a little pond is quietly approaching the problem of climate change from a different angle. Author Ian McEwan has done the unthinkable: He’s taken climate change – that boring, science-heavy, amorphous, overwrought subject – as the backdrop of his new novel. The new book is still in the works, but has been discussed in a New Yorker profile, interviews, and at a writer’s conference in August.

This is big for literary types, who know McEwan as the British master of perfectly economical fiction, dubbed “England’s national author,” by the New Yorker. And it should come as exciting news to film buffs, who know him as the author of Atonement, recently made into an Academy Award winning film starring Kiera Knightley and James McAvoy.

But the news should also cheer environmentalists, who may know McEwan as the very famous author whose name has started popping up in green blogs next to phrases like “global warming,” and “melting arctic,” and whose home is topped with solar panels. If we’re going to beat climate change, after all, we’ll need to employ every tool at our disposal – including literature.

Apparently, McEwan has wanted for years to write a novel about climate change, but was at a loss for a way in to the subject. So McEwan decided to get in there and live his subject for a spell. He spent a week with a group of artists and scientists on a research boat frozen into a Norwegian fjord. Just another day in the office.

McEwan’s icy visit did the trick. He explained at a writer’s conference this summer: “What I understood from my week in the arctic was that the way into this subject was of course human nature. And so, slowly, and I wrote two other novels while this was going on, a person began to appear, into whom I would pour every human fault I could think of. And one day, the opening sentence of the novel occurred to me: ‘He belonged to that class of men, vaguely unprepossessing, often bald, short, fat, clever, who are unaccountably attractive to certain beautiful women. Or, he believed he was, and thinking seemed to make it so.’”

Michael Beard is the name of this repulsive new protagonist of McEwan’s. He’s a washed-up, once Nobel-winning physicist with no new ideas. As McEwan puts it: “He’s devious, he lies, he’s predatory in relation to women; he steadily gets fatter through the novel. He’s a sort of plate, I guess. He makes endless reforming decisions about himself: Rio, Kyoto-type assertions of future virtue that lead nowhere.”

If McEwan fans out there are wondering whether such a potentially dry, depressing subject matter as climate change will prove dangerous fodder for fiction, they’re not alone. McEwan himself mused in a recent interview: “That’s another problem with writing about climate change – it’s full of facts and figures. We’re putting into the atmosphere 16 gigatons of carbon every year; it takes 16 terrawatts to run civilisation. It’s very necessary to keep these out [of the novel]. My character is engaged in a project to use light to split water, imitating something of the process of photosynthesis. Even writing sentences about splitting water into hydrogen and oxygen, already I know that about half the readers [will] see the names of those gases and their minds white out. Just seeing the word ‘hydrogen’, they panic.”

So perhaps gigatons and terrawatts and hydrogen don’t scream Pulitzer. But let’s keep the faith, shall we? When Atonement hit shelves in 2001, The Christian Science Monitor raved: “The extraordinary range of Atonement suggest that there’s nothing McEwan can’t do.”

Surely, that includes climate change? Who knows, maybe the new novel will turn out to be the Uncle Tom’s Cabin of climate change, and even make waves in Washington.