The Pale-Bearded Ghost of John Berryman Haunts Us Still

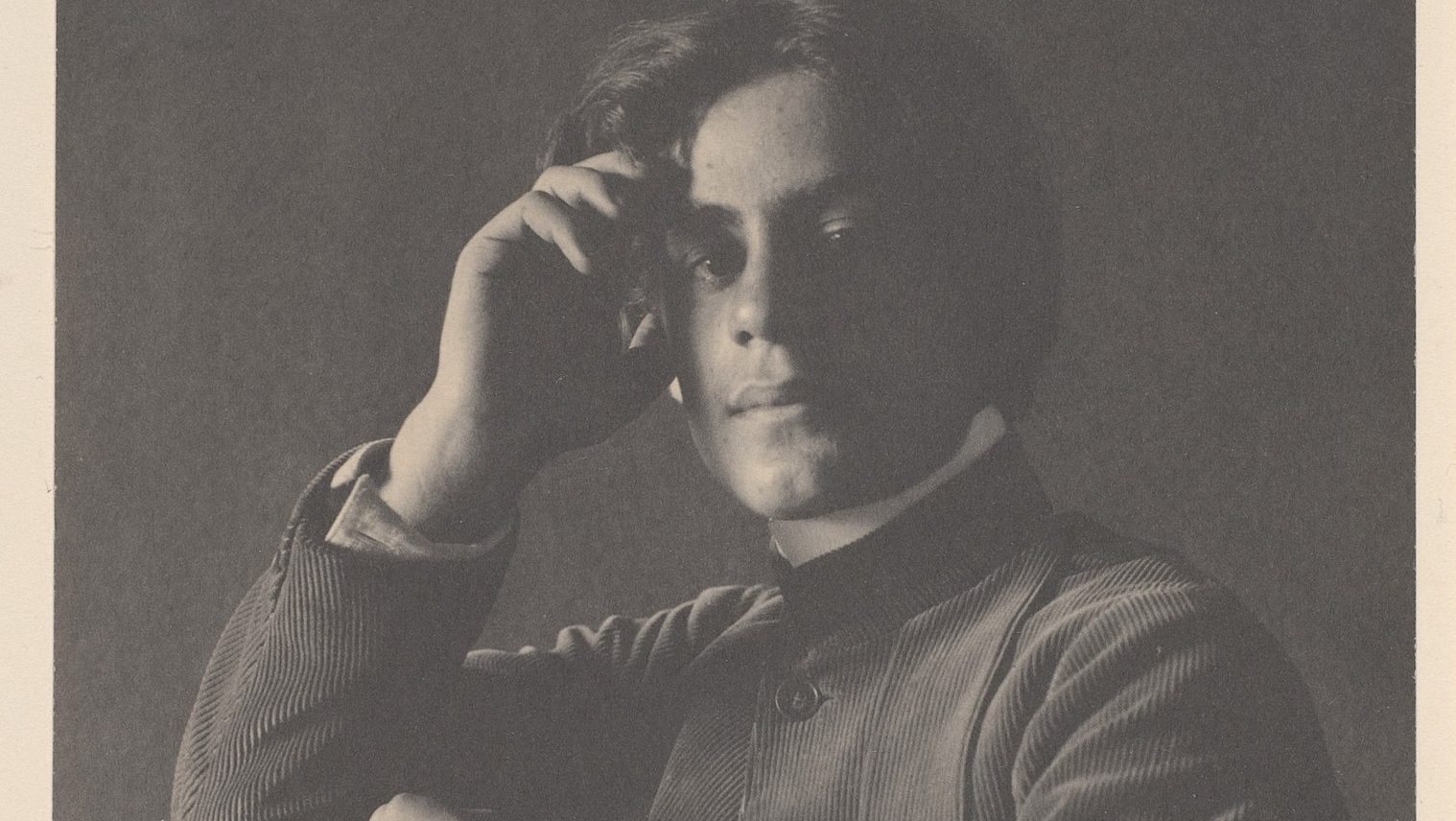

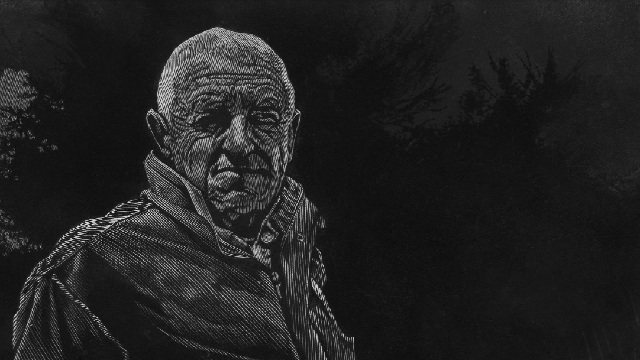

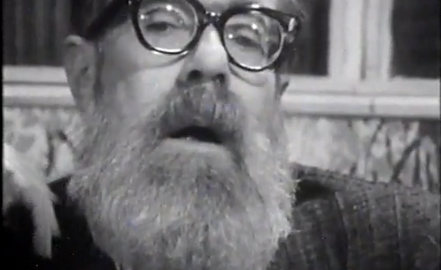

This winter, John Berryman will have been dead for forty years. That figure strikes me as strange; in many ways Berryman’s poetic voice still sounds like that of a fearless contemporary. Then again, his recorded voice sounds like no one who ever lived.

Eccentric, tormented, suicidal, Berryman was among the leading figures of that eccentric, tormented, suicidal school known as the Confessional poets. At least, that’s how he’s sometimes categorized; Berryman himself would have scorned any such affiliation, having once called his work “hostile to every visible tendency in both American and English poetry.” And in fact, unlike his contemporary, the arch-confessional Robert Lowell, Berryman’s self-revelations are framed less as verse memoirs than as harrowing plunges into the unconscious, with results that are less juicy than jarring and bizarre.

His book-length poem Homage to Mistress Bradstreet (1956) remains admired, and is an important stylistic precursor to his later work. These days, though, most people come to Berryman through, and for, the Dream Songs.

It’s a critical commonplace that “Henry,” the main poetic persona of the Songs, is an alter ego for Berryman, despite the poet’s insistence that he was an autonomous character. To call this blindness or disingenuousness would be to miss the point: for Berryman, he was autonomous enough to provide the slight estrangement necessary for self-revelation. More than Lowell, Berryman needed an “angle” on his autobiographical material, and the thin disguise of Henry provided that angle. (Lowell in 1964: “Henry is Berryman seen as himself, as poète maudit, child and puppet. He is tossed about with a mixture of tenderness and absurdity, pathos and hilarity that would have been impossible if the author had spoken in the first person.”)

As for the Dream Songs themselves, some are failed experiments, but all are strikingly original and a handful are true classics. The poems in the second collection (His Toy, His Dream, His Rest, 1969) are both more numerous and less successful than those in the first (77 Dream Songs, 1964), but I disagree with Donald Hall’s high-handed view that they shouldn’t have been written at all:

John Berryman wrote with difficult concentration his difficult, concentrated Mistress Bradstreet; then he eked out 77 Dream Songs. Alas, after the success of this product he mass-produced His Toy, His Dream, His Rest, 308 further dream songs—quick improvisations of self-imitation, which is the true identity of the famous “voice” accorded late Berryman-Lowell. (Hall, “Poetry and Ambition,” 1983)

This lumping-together with washed-up Lowell is unfair, as is Hall’s brisk dismissal of the entire second collection (“mass-produced” over the course of five years). The later songs remain more playful and passionate than the poetry of Berryman’s early career, and the style remains totally his own, so why shouldn’t he have kept mining the same vein?

The uneven quality of the Songs makes the best ones easy to pluck out; anyone unfamiliar with Berryman should start by reading the anthology pieces #1 (“Huffy Henry hid the day”), #4 (“Filling her compact & delicious body”), #5 (“Henry sats in de bar & was odd”), #14 (“Life, friends, is boring”), #29 (“There sat down, once, a thing on Henry’s heart”), and #324, the elegy for William Carlos Williams. But there are many other gems as well, including #19, which ends with some of the most mordant lines of political verse ever written—a kind of timeless verdict on Wall Street and the Beltway:

Collect in the cold depths barracuda. Ay,

in Sealdah Station some possessionless

children survive to die.

The Chinese communes hum. Two daiquiris

withdrew into a corner of the gorgeous room

and one told the other a lie.

“Survived to die” would be a fitting epitaph for Berryman himself. After weathering fifty-seven punishing years of alcoholism and depression, he killed himself by jumping off a Minneapolis bridge. The ghoul of his language—twisted, offensive, violent, and terribly funny—retains such power to disturb that it can seem as though he never left.