The Matrix: The Political Dance of Modern Drawing at the MoMA

You can always count on the MoMA for two things: high-concept theme shows and high-concept theme shows that go in directions you didn’t expect. On Line: Drawing Through the Twentieth Century, which runs through February 7, 2011, begins as you’d expect with the big boys of modernism. Just as the testosterone threatens to thicken, however, the narrative line turns toward the feminine. The phallic gives way to the “matrixal”—a connective and even curative matrilineal web of associations woven by modern women artists that redefines drawing practice to include all forms of human gesture, even the dance. This dance turns political as artists tango through the minefield of modern life to bring the world a little closer. At times this “matrixal” theme seems almost as esoteric and abstract as The Matrix movies, but ultimately the show brings you back to firm ground and the stars align once more.

“Line experiences many fates,” Wasily Kandinsky wrote in his 1919 essay, “On Line,” the inspiration for the current exhibition’s title. “Each creates a particular, specific world, from schematic limitation to unlimited expressivity. These worlds liberate line more and more from the instrument, leading to complete freedom of expression.” On Line follows as many of those fates as possible on the adventure towards total liberation from “the instrument.” In her catalogue essay, Guest Curator Catherine de Zegher, former Director of The Drawing Center in New York City and currently Co-Director of the 18th Biennale of Sydney, writes, “Seen as an open-ended activity, drawing is characterized by a line that is always unfolding, always becoming.” This ever-becoming (which made me think of Martin Heidegger’sBeing and Time for its philosophical counterpart) plays out in the earliest movements of modern art, especially the introduction of collage by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque during the Cubist glory years. De Zegher proceeds to follow the line of modern drawing’s patrimony through figures such as Marcel Duchamp, Paul Klee, and Kurt Schwitters. Russian artists such as Kazimir Malevich, El Lissitzky, and especially Alexander Rodchenko emerge as much more influential and interesting in this storyline than they do in standard modern art histories, in which they’re often more mourned as political victims than celebrated as art theorists. In On Line, these utopian-minded Russians receive credit for seeing the freedom of line as an analogue to freedom in society, even if the Socialist dream turned into a nightmare. Similarly, the Neo-Concretists and Arte Povera “aimed to reconnect art with daily life, to liberate the art object from its formalist inertia by creating ‘living objects’ in which could be glimpsed the primary energy, the endless process,” de Zegher explains.

As de Zegher traces the course of modern drawing, the number of influential women artists grows—slowly at first with figures such as Sophie Tauber-Arp and a few others—eventually reaching a critical mass with Eva Hesse, Agnes Martin, Lygia Clark, and many others. The liberation of the line into a “transdisciplinary” realm parallels the liberation of the woman artist, thus creating an intersection of aesthetics and social progress. “Confusing the disciplines of drawing, sculpture, and painting,” de Zegher suggests, “these women shaped a radically different dynamic in art, promoting a model of transsubjectivity—a reciprocal attitude the anticipated the concept of the ‘matrixal,’ theorized in the 1990s by the artist and psychoanalyst Bracha Ettinger.” The Fathers of Modern Drawing thus give way to the Mothers of Invention, who bring in everything at hand, especially “female” arts such as textiles and dance, to the concept of drawing as gesture and becoming. Whereas line before had demarcated separation, the “matrixal” line connected disparate dots and healed all rifts.

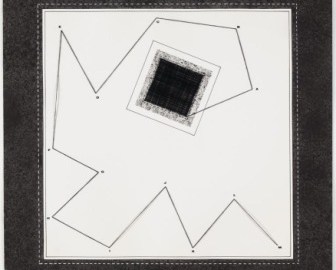

“The contemporary conception of drawing,” de Zegher continues, “emphatically stresses reciprocity and empowerment, acknowledging that a single line can challenge and change the understanding of the ground itself.” Works such as Anna Maria Maiolino’s Desde A até M (From A to M) From the series “Mapas Mentais” (Mental Maps) (shown above) rework the theoretical landscape of the “mental map” of drawing and allow for disenfranchised voices to be heard rather than drowned out by the din of the Picasso crowd. Women artists, de Zegher contents, lead a chorus of “compassionate witnessing” that the 21st century will need to negotiate the new global reality and to survive.

The MoMA’s Chief Curator of Drawings Connie Butler, co-curator of On Line, continues de Zegher’s argument in an essay paying special attention to the role of the dance in modern drawing. From the early films of Loie Fuller’s flowing dance lines to Yvonne Rainer’s regimented breakdown of a language of dance in Trio A, dance and drawing become intertwined and mutual inspirations. (A drawing by Nijinsky of a dancer, of course, even appears in the show.) This dance of drawing takes on political overtones as well. “Many dance- and line-based works of art since the 1980s involve a notion of line as political,” Butler writes, “a deployment of line in the space of the political and social.” Movement of the body in dance becomes movement of the body politic—a gesture not just of art but of life itself, usually in the pursuit of freedom. Even a gesture such as drawing a line in the sand with a foot becomes a cry for freedom—the ultimate act of power through artistry.

The sheer variety of artists in On Line—100 artists represented by 300 works—sets your head spinning, in a good way. Most of the expected names appear (with the conspicuous exceptions of Matisse and de Kooning). Pleasant surprises, such as Georges Vantongerloo, shine in unexpected ways in the context of the exhibition’s concept. Rather than taking a by the numbers approach, the curators take the risk of challenging the audience, which for the greater part pays off. There remains a risk of the art being too abstract, too far out there—often ironically in the name of connecting with society. For those who still associate drawing with realism and the draftsmanship of the Renaissance masters, On Line may seem to have nothing to do with drawing at all. For those who open themselves up what everyone since Kandinsky, On Line’s guiding spirit, has tried to make the line do—literally, nothing less than save the world—this exhibition might actually sway them to the side of modern art. On Line suggests ultimately that all of us are artists, each drawing the reality of our individual lives, but also looking for a way to make those individual lines (and individual lives) connect.

[Image:Anna Maria Maiolino (Brazilian, born Italy 1942). Desde A até M (From A to M) From the series “Mapas Mentais” (Mental Maps). 1972-1999. Thread, synthetic polymer paint, ink, transfer type, and pencil on paper. 19 5/8 x 19 1/2″ (49.8 x 49.5 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Purchase. © 2010 Anna Maria Maiolino.]

[Many thanks to the MoMA for providing me with the image above, press materials to, and a copy of the catalogue to On Line: Drawing Through the Twentieth Century, which runs through February 7, 2011.]