The Future of Space Exploration: A Hitchhiker’s Guide

What’s the Big Idea?

With the end of the space shuttle era, and the United States no longer able to put people in orbit without the help of Russian or Chinese rockets, Texas Governor Rick Perry accused the Obama administration of leaving U.S. astronauts to “hitchhike into space.”

For Governor Perry, who may be running for President in 2012, all politics is local. His state is home to the Johnson Space Center, which directly employs 3,000 people, as well as 12,000 contract positions from outside companies. Perhaps a third of those jobs now stand to be lost.

Space exploration has always been a political football. As the Space Science Institute’s Heidi Hammel tells Big Think, the motivation for funding the human exploration of space was never about science, “and don’t let scientists tell you otherwise. That just means they haven’t read history.” Hammel continues:

We were not doing moon landings to do a geological exploration of the surface. In fact, when we got to that point, the program was canceled. The only way that the U.S. human spaceflight program will ever be revitalized is if some other country, perhaps China…landed on the moon…and brought back our American flag and put it in Tiananmen Square.

As Paul Halpern, professor of physics at the University of Science in Philadelphia put it plainly in an opinion piece for the Philadelphia Inquirer, major scientific endeavors like space exploration and the development of the James Webb Space Telescope (which was recently defunded by Congress) take many years of planning and require “dedicated funding sources that can weather economic downturns.” The problem with this model, of course, is our political system, in which Congressmen are elected every two years, and certain pet projects often gain and lose favor depending on which party may be in power.

At this moment in time, as the federal government prepares to tighten its fiscal belt, our ability to make advances in space is very much in question. For instance, the NASA leadership appointed by President Obama has indicated it will focus on deep space exploration–manned missions to an asteroid and Mars–but there is no clear plan yet. After all, there seems to be very little political will to drum up the Apollo-like enthusiasm that would be required for such a mission.

But don’t tell that to visionary thinkers like Peter Diamandis, who founded the X Prize Foundation. Diamandis sees the next two decades as “the moment in time the human race is making the irrevocable transition beyond the earth.” What will drive this transition into space? Diamandis says that raw materials in space, “the things we fight wars over,” offer unprecedented rewards for commercial enterprises. We just need to get there, and cheaply.

The race is already underway. 29 companies, such as the Silicon Valley venture Moon Express — launched by the billionaire Naveen Jain — are competing for the $30 million Google Lunar X Prize, a competition to become the first private venture to land on the moon. Jain is reportedly spending $70 million to $100 million on the project, but is betting he can recoup the costs with a single lunar landing. The surface of the moon is dotted with craters formed from collisions with metallic asteroids. The Moon Express is preparing to “mine the moon for precious resources that we need here on Earth.” The opportunities don’t end there. From robots scrawling marriage proposals in the lunar dust to corporate sponsorship and video broadcast rights, a lunar landing is “probably the biggest wealth creation opportunity in modern history,” according to Moon Express co-founder Barney Pell.

Another company, Pittsburgh-based Astrobotic Technology, plans a larger ‘lunar lander’ that The New York Times reports will be “capable of carrying 240 pounds of payload (read: $200 million of cargo)” and has a launch date set for December, 2013. (The X Prize competition ends in 2015).

What’s the Significance?

The retirement of the space shuttle and the birth of the commercial space race is one of many developments that will impact the future of space exploration. A Congressional Committee voted on July 7th to cut funding to the Webb Space telescope, the planned successor to the famous Hubble Space telescope. The project is said to be 75 percent complete, but will be effectively dead if the funding is not restored.

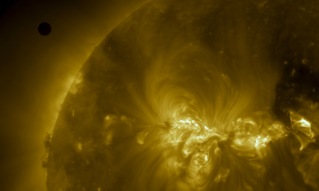

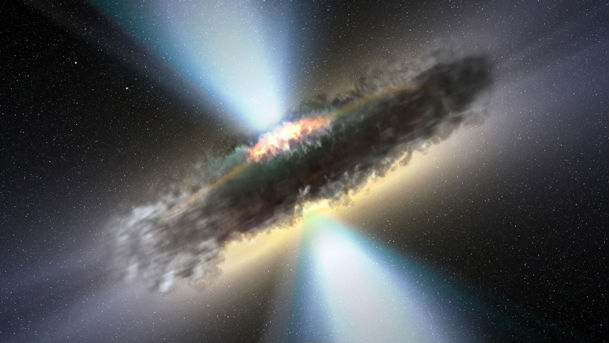

According to Big Thinker Dr. Michio Kaku, the Hubble “is perhaps the most cited scientific instrument of all time,” based on citations in science journals. The Hubble’s greatest hits include: proving “the existence of black holes lurking in the center of galaxies”; providing the most complete life-history of stars, from star formation to supernova; providing the most detailed photographs of the planets, comets, asteroids and galaxies besides photos from space probes; providing evidence for the existence of dark matter, and also proof of Einstein’s theory of relativity.

NASA chief Charlie Bolden, in his testimony before Congress, said the science returns for Webb would be even greater.

It is not clear to what extent private industry will be able to step in and take the lead in space exploration. What is at stake, however, is very clear: the competitive edge the U.S. aerospace industry has enjoyed for so long.