Sweden’s Approach to the Sex Trade: Let the Buyer Beware

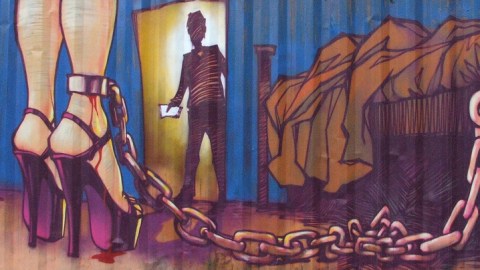

Sometime I wonder why there isn’t more creative energy applied to finding solutions to social problems that have been created by the proliferation of the sex trades. The debate around policy appears to be driven by those with political (and moral) agendas in such a way that two distinct camps have emerged: those who favor criminalization and those who favor legalization. Neither of these extreme approaches completely solves the problem of violence and exploitation of the women and men who operate on these markets. And so we have resigned ourselves to a debate over which policy minimizes the harm, while shrugging off the possibility of eliminating it all together.

The government of Sweden in 1999 clearly had a political agenda. They decided that there was no place for the sex trades in a country that firmly believes in equality by gender, and so set out a series of policies with the goal to abolishing the industry all together. In a change to the penal code they legalized the right for a sex worker to sell his/her body while maintaining that the buying of those services is a criminal act. At the same time they recognized the need for social programs to help sex workers transition out of the industry and to prevent the young and vulnerable from entering.

The basic assumption made was that the sex trade industry is driven by demand; eliminate the demand and eradicate the industry.

Last year an inquiry into the effectiveness of this policy found encouraging results: immediately following the policy’s implementation, the number of sex workers in the Swedish street sector fell by half, and has stayed at that low level ever since. The inquiry recognized the possibility that increased Internet activity might have caused a sector shift away from the streets to indoor sex work. To see if this was the case they undertook a comparison between the number of sex workers in Sweden and on the streets in their neighbouring countries, Norway and Denmark. Neither of these countries had a similar ban on the purchasing of sexual services in the 1999 to 2008 period, although Norway has since brought in such a ban.

The inquiry found that although the number of sex workers on the streets of the three capital cities was very similar before the ban, ten years later Norway and Denmark had three times more street sex workers than Sweden. They also find while the number of foreign women in the street sex trade in Sweden has increased, the number in Norway and Denmark has increased by more.

The figure I have include below plots the number of sex workers on the streets by year (1998 to 2008) for each of these three countries.

So, can we call the policy a success? Should my country, Canada, for example, consider implementing a similar policy? I would love to say yes, but to me this data tells a very different story to that being suggested in the report, one that raises doubts about the effectiveness of criminalizing the purchasing of sexual services. The policy may have decreased domestic demand, but the inquiry report no doubt overstates the decrease in overall demand. To me this evidence suggests that following the implementation of the new policy, the demand for market sex was simply pushed out into neighbouring countries and, while this may have reduced some of Sweden’s social problems, it has done so at the expense of their neighbors’. Maybe that is alright if countries are entirely self-interested, but the problem is that we can’t evaluate the success of a policy that targets the purchasing of sex work based on these results alone. We don’t know what would have happened if Norway, Denmark and Sweden (or in fact any other country with which Sweden is economically integrated) had all implemented identical bans simultaneously.

This problem is aggravated by the fact that the Swedish law only prohibits the purchasing of sex by Swedish nationals in a foreign country if that purchase contravenes the laws of that country; they require “dual criminology.” Now that Norway has also criminalized the purchasing of sex, Swedish courts have the power to pass judgement on Swedes traveling into Norway to buy sex. If they act on that power it will be very interesting to see the response in the domestic sex market.

International considerations aside, markets exist to bring buyers and sellers together. Laws that punish buyers may reduce demand, but they also shift the market underground making it more difficult to evaluate its extent. The inquiry acknowledges its limitations in this regard but is satisfied with the fact that there is no evidence to suggest that the indoor sex sector has increased more than its neighbors’.

The flip side of that argument is, of course, that there is no evidence that it hasn’t.

Thank you to Teresa MacInnis for sending me the original report with the English summary (starting on page 28) and to Nippe Lagerlöf for helping me with the Swedish parts.