Smoke and Mirrors: Forensic Science, Art, and Democracy

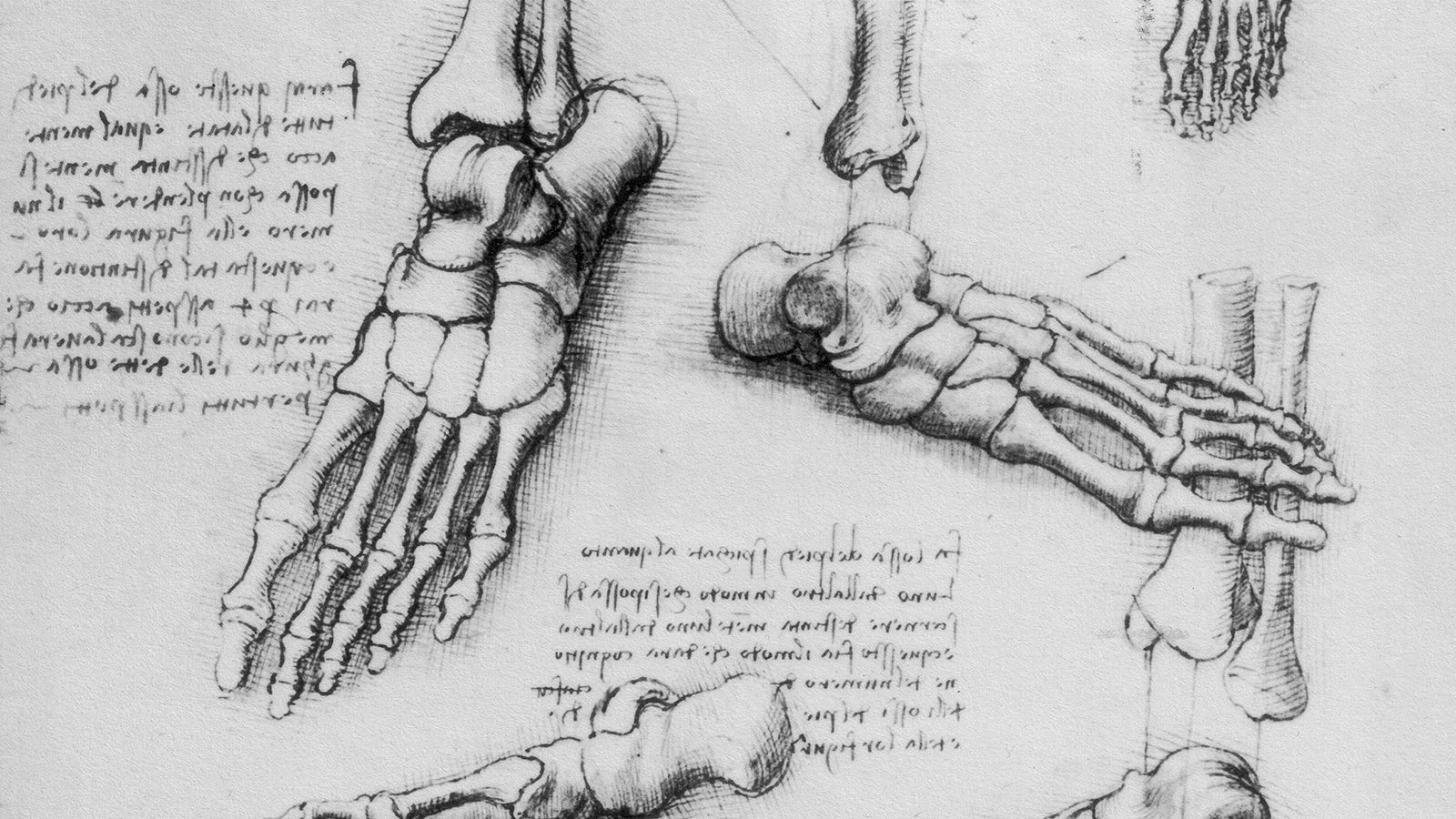

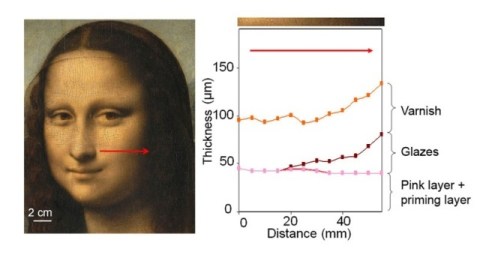

Leonardo da Vinci didn’t invent the sfumato technique, which produced the “smoky” effects of masterpieces such as the Mona Lisa, but he may have perfected it. For centuries, art experts have longed to discover Leonardo’s secret. Until recently, to uncover that secret, part of the work itself would need to be destroyed. Today, however, we no longer need to “murder to dissect.” Using noninvasive x-ray fluorescence, a French team peered into the layers Leonardo meticulously applied to create Mona’s smoky eyes and enigmatic smile. Going where no art connoisseur had ever gone before, have these scientists made the soft science of art expertise obsolete? Or are art forensics just the latest version of smoke and mirrors?

The Laboratoire du Centre de Recherche et de Restauration des Musées de France, led by Philippe Walter, collaborating with the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility and the Louvre Museum, determined chemically that da Vinci devised no less than four different recipes for the glazes that make up the shadows around Mona’s face. The artist applied the glazes in layers as thin as 1 to 2 micrometers. The total thickness came to no more than 30 to 40 micrometers—approximately half the thickness of a human hair. The scientists published their findings in the July 15, 2010 international issue of the chemical journal, Angewandte Chemie. For those who can’t understand the technical-ese and fancy charts, their findings fascinate but still don’t penetrate the general consciousness of art lovers beyond confirming the general consensus that da Vinci was a genius.

Such art forensics seem to be the brave new world of art study, especially of well-known figures and works. David Grann’s “The Mark of a Masterpiece” in a recent issue of The New Yorker profiled perhaps the most famous (or infamous) art forensic specialist, Peter Paul Biro. Grann raises an interesting point in suggesting the power of art forensics to take art connoisseurship out of the hands of the elite and put it in the hands of the people, who can read the scientific reports for themselves rather than take the word of a self-appointed expert. Grann sees this as a “democratizing” of the art world, perhaps even to the point of bringing it to the masses in a whole new way. Grann raises that question only to knock it down quickly as he calls into question the legitimacy of some of Biro’s findings. If Biro somehow is planting the evidence he claims to find as proof of a masterpiece, can we believe anything we are told about great art? Do we go scurrying back to the art connoisseurs with their judgment calls, or can we believe in science?

Sir Geoffrey Crowther coined the term “numeracy” to describe the facility someone has to understand mathematical concepts, thus indirectly describing the lack of that talent, or “innumeracy.” John Allen Paulos titled his 1988 book Innumeracy: Mathematical Illiteracy and its Consequences, with an accent on the “consequences” for democracy. People unable to understand basic math will be open to manipulation by fancy statistics, just as the illiterate can fall for anyone with a gift for rhetoric. This Mona Lisa study and the Biro profile raise the issue of “art literacy.” As science soars higher and high above the heads of the average person, the threat that it can lose touch entirely looms heavily. Science can become the new god (as it has many times in the past) taken on faith rather than reason. As fleetingly as Grann lauds this new wave of scientific art study as a democratizing force, I still fear that it can also be a way of leaving us open to art history “fascism.” The new science can be the new unquestionable authority. Perhaps the real solution is a combination of science and human judgment—head and heart. Only then can we be secure that the assessment of either authority alone is more than just smoke and mirrors.