Rainbow Connection: Rock Music Illuminated by Andi Watson

“It never phased him that we’d call out different tunes from the stage and change the set around endlessly to stop from being bored,” Radiohead front man Thom Yorke says of the group’s lighting and stage designer Andi Watson. “It meant that it became less of a show of self aggrandizement for the artist, impressing an audience for its own sake and filling a huge space, and more a response to what was really happening musically night by night.” In Bullet Proof… I Wish I Was: The Lighting and Stage Design of Andi Watson, Christopher Scoates and others examine just how Watson sculpts light to help audience connect with the music of acts such as Lenny Kravitz, Oasis, Counting Crows, and especially Radiohead, with whom Watson’s worked since meeting them in 1993 up to and including their last tour in support of In Rainbows. Using the whole spectrum of aesthetics and technology, Watson’s “rainbow connection” with audiences not only draws heavily from artistic influences of the past, but also spotlights a brighter, greener future for the field of lighting and stage design.

Scoates and fellow essayists J. Fiona Ragheb and Dick Hebdige each approach the history of lighting in different ways to arrive at how Watson fits into that history. Scoates, director of the University Art Museum, California State University, Long Beach, presents the whole history of stage lighting, beginning with Adolphe Appia, the “father” of the discipline working at the turn of the twentieth century; moving through the experimental lighting of fine artists such as Laszlo Maholy-Nagy and Francis Picabia; tripping to the psychedelic 1960s lighting of Glenn McKay and Mark Boyle; and culminating with Watson’s closest artistic predecessors, Mike Leonard and Mark Fisher, best known for creating the look of Pink Floyd concerts such as the monumental The Wall Tour. Scoates parallels this stage ancestry with art history influences such as German Expressionism, Cubism, Dada, and even Surrealism he finds in Watson’s work.

Ragheb expounds on the use of light by artists in the twentieth century. A recent European ruling that light-based works by Dan Flavin and Bill Viola don’t qualify as art for customs purposes shows that the genre still fights for respect, but Ragheb makes a strong argument for a higher profile. Like Picabia, Ragheb believes, Watson “uses light to dissolve the invisible plane that serves to separate and isolate audience from performer,” echoing Yorke’s sentiments. “Under Watson’s tutelage,” Ragheb continues, “light assumes the condition of sculpture,” thus extending the work of Donald Judd, Carl Andre, and the Minimalists. Watson the Minimalist thus “rejects the jarring barrage of lights and images associated with the contemporary rock concert experience in favor of an austere approach,” Ragheb writes. Less is more, not that Watson ever gives less of a show.

Hebdige, a professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara, takes the most interesting approach of the three by exploring the “dark side” of lighting. A fascinating panoply including the torchlight parades of Hitler’s Germany, the “Auto-Destructive Art” of the 1960s (think Jimi Hendrix torching his guitar), Robert Rauschenberg’s Open Score, and even the 9/11 Tribute in Light all add up to a devilish “Lucifer setting” that influences Watson by antithesis. Where they chose destruction or loss as their subject, Watson chooses creativity and life.

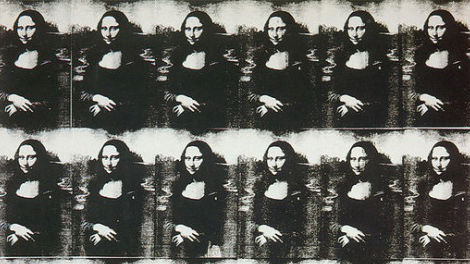

In the single photo of Watson in the book, he appears only as a silhouette sitting at a control panel. The real star of the book is Watson’s work, which Scoates displays with a generous selection of images from many shows by many artists. For me, the most fascinating show is Radiohead’s In Rainbows (an image from which appears above). Scoates wonderfully describes how Watson sought to create an “LED forest” to act as an environment for the band to play within, much like Walter De Maria’s Lightning Field. Such an environment values “visceral impact” over “narrative meaning” in Scoates opinion. In addition to the aesthetic beauty of the In Rainbows stage, the design stands as the first 100% carbon-neutral stage set—an ecologically friendly step in line with Watson and Radiohead’s green dream led by the “eco-coordinator” hired to make every element of the tour good for the environment. Such details make Watson truly a visionary thinker in the field of art.

“My job,” Watson tells Scoates, “is to give life to what I have designed, and I don’t mean in a Frankenstein way—I just mean in terms of the fact that it is alive, and I allow it to react to the music, and all I am is just this thing standing in the middle of the music and the light.” Watson translates the music into the language of light for those in the audience to experience with both their ears and eyes, thus reaching their heads and hearts even more deeply. Bullet Proof… I Wish I Was: The Lighting and Stage Design of Andi Watson will undoubtedly attract fans of the musical acts Watson collaborates with, but they will assuredly come away fans of Andi Watson—the shadowy figure at the controls who lights the way for music and art to reach new heights.

[Many thanks to Chronicle Books for providing me with the image above and a review copy of Bullet Proof… I Wish I Was: The Lighting and Stage Design of Andi Watson by Christopher Scoates, with a foreword by Thom Yorke and essays by Dick Hebdige and J. Fiona Ragheb.]

[All apologies to Kermit the Frog for borrowing the title of his hit song for the title of this post.]