Proof That People Are Prejudiced Against Breast-Feeding Women? Not So Fast

This study just out in Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin claims to have found a general societal prejudice against women who breast-feed. Reports about the work concurred. But I think it works better as an example of what’s wrong with our conceptions of prejudice. It’s also good fodder for critics who say social psychology has methodological issues and maybe even a little left-wing bias.

Here are the experiments that led the authors to conclude that bias about breast-feeding creates a “social cost” for American women who do it. In one, 30 students answered questions about their views on Brooke Shields, after being told that she’d written a book about motherhood. Half were told the book discussed (among other parental topics) breastfeeding, while the other group learned that the book talked about Shields’ experiences with bottle-feeding. Men and women who thought Shields had breast-fed saw her as warmer and friendlier, but “significantly less competent in general, and less competent in math specifically,” the paper says (according to Tom Jacobs’ solid and detailed story on Miller-McCune; as the study is behind a paywall, I was only able to get the abstract).

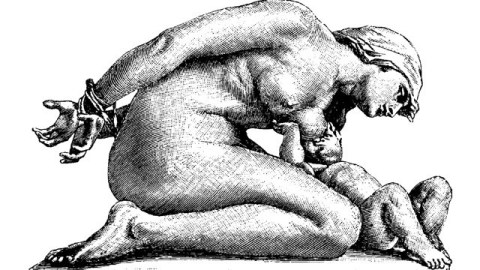

A second study asked students to give their impressions of a woman based on a message about arrangements for a dinner, left on her answering machine. The 55 students were divided into four groups. One heard “I figured you would want to go home and breastfeed the baby”; a second group heard “I figured you would want to go home and give the baby a bath.” And the third cohort heard “I figured you would want to go home and change into your strapless bra.” Finally, a control group heard a completely neutral message.

Asked to rate the woman as a job candidate, the students (men and women alike) gave the lowest rating to the breastfeeding woman, with second-lowest rank going to the strapless-bra lady. But the woman going home to bathe her baby did roughly as well as the one who received the neutral message. In other words, signs of parenting didn’t trigger perceptions that the hypothetical woman was less capable. Rather, that result appeared after people were primed to think about the woman’s breasts. It didn’t matter much if they were being invoked as a source of food or as a source of pleasure.

That’s an interesting experiment. But it doesn’t justify the researchers’ claim that “breastfeeding is a devalued social category.” Their evidence instead found that when people are prompted to think about a woman’s breasts, they will, immediately afterward, perceive her as less well-fitted to the world of work. Their own study found that this effect isn’t confined to breast-feeding (the sexy-bra prompt had the same impact on the people in the experiment).

What if the effect is not confined to breasts? Suppose the students had had to judge a hypothetical man’s messages, one of which referred to Viagra and another to a prostate exam. If they saw him as less competent, that would suggest a general effect of stereotypes: If you remind me that Person A has a sexual identity and then ask me about their suitability for a non-sexual role, I will see them as less suitable.

Of course, the results of my imaginary Viagra experiment might come out differently than I imagine at first, um, blush. I’m not trying to predict the outcome here. I’m just saying the experiment ought to be done. Without some tests of alternative explanations for the result, you can’t jump from this result to the conclusion that people have a prejudice against breast-feeding. That’s the methodological issue often raised by critics of social psychology: The prosecutor’s fallacy of claiming evidence that fits a hypothesis has proved the hypothesis.

Other experiments suggest that priming people with stereotypes affects their behavior, in both desirable and undesirable ways. In this 1999 study, Margaret Shih and her colleagues reminded some women before a math test that they were women, and found that they scored worse than women who had not gotten that message. On the other hand, in that same experiment women reminded that they were Asian-American did better than other women on that test.

This new study also found that stereotype cues can prompt people to see the same person in different ways (Brooke Shields the bottle-feeding math ace versus Brooke Shields the breast-feeding airhead). If breast-feeding has a consistent “social cost,” then, the effects of that stereotype must outweigh and outlast the effects of other, more positive primes. If that weren’t so, then breast-feeding mothers could counter the effects of those stereotypes by invoking others.

Which is, of course, what common-sensical people do. If I want someone to pay me to write something, I probably won’t discuss my son’s teething issues. This is because the stereotypes raised by mentions of my book and writing history are more consistent with the task at hand than are stereotypes of dads with cranky babies. It is not because society has a shameful prejudice against fathers with screaming kids, which all of us must dutifully repair.

Of course, it may be that stereotypes that invoke human biology do have more power than work-based stereotypes like “high-powered executive” or “tenured biologist.” No one knows how such an experiment would turn out (if anyone did, it wouldn’t be an experiment, and it wouldn’t be necessary to do it). What I’m wondering about is why the authors didn’t think it needed to be done. Whe instead they announced that society needed fixing because of its general prejudice against something the authors (and other right-thinking members of the species Homo academicus) generally support.

I suspect that leap to a conclusion from these results is an example of the ideological blinders that Jonathan Haidt has been decrying lately. (Might that also explain why the study seems to treat the devaluation of the strapless-bra woman as unsurprising and unalarming.)

Why pick on one study that reported an interesting result? Because I noticed that not one media report about this article took a step back to ask about the path from experiment to conclusion. Every time people like me give these kinds of claims a free ride, we encourage a dumbed-down conversation about mind science—one in which all claims either go unchallenged or get met by ideologically-motivated criticisms (“your sample was too small and only included left-handed college students!” or “your research was paid for by George Soros!”). If we want to understand what the behavioral sciences can tell us about ourselves, we’re going to have to do better than that.

Smith, J., Hawkinson, K., & Paull, K. (2011). Spoiled Milk: An Experimental Examination of Bias Against Mothers Who Breastfeed Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin DOI: 10.1177/0146167211401629

Shih, M., Pittinsky, T., & Ambady, N. (1999). Stereotype Susceptibility: Identity Salience and Shifts in Quantitative Performance Psychological Science, 10 (1), 80-83 DOI: 10.1111/1467-9280.00111