Members Only: Relics of the Age of Relics and Reliquaries

Those of us who lived through the 1980s remember well the phenomenon of the Members Only jacket. Whether you’ve found one in the back of your closet or not, you can’t help but look back and wonder what we “members” were thinking. A similar phenomenon surrounds the modern perception of the medieval cult of relics and the precious reliquaries that once housed them. In the exhibition Treasures of Heaven: Saints, Relics and Devotion in Medieval Europe, currently at the Walters Art Museum through May 15, 2011, modern pilgrims can see that the cult venerated not just members (such as the arm bones once inside the arm-shaped reliquary shown), but any souvenir of the sacred from items related to the life of Christ to even stones or water taken from the Holy Land. Gaining an appreciation of the allure of such objects opens a window onto a medieval world at once very different than our own and yet somehow a precursor of our own cults and memberships.

“At the center of the practices [of relics] lay a basic confidence that matter—fragments of bodies, oil, water, even bits of stone and dust—could contain and convey spiritual power,” writes Derek Krueger in the catalog published by Yale University Press. Things were holy by sheer proximity to holy people, places, or things. Pilgrims traveled long distances just to be near these relics and bask in the radiating holiness. When the age of martyrs passed in the late fourth to early fifth century AD, the faithful sought out “living saints” to be near. Some stricken by illness actually slept near the remains of a saint hoping for a cure in a practice known as “incubation.” Above all, “[t]he religion of relics provided material solutions to… practical concerns” such as “health and prosperity in this world and salvation in the next,” Krueger continues, summing up the widespread appeal of old bones and stones to the medieval mind.

Arnold Angenendt outlines the philosophical underpinnings of the cult of relics. “In early Christianity,” Angenendt explains, “the religious and theological presuppositions required for the veneration of relics were absent at first.” Early Christians valued the words of Christ above physical remains, which were trappings of a physical world valued far less than the spiritual world. When martyrs began to die for Christ, however, their bodies became objects of veneration as the signs of their sacrifice for their faith. Angenendt belives that martyrdom helped build “an interpretive framework that would remain definitive from this point forward: the soul in heaven remains in contact with the earthly body, which shall renew itself at the Resurrection,” leading to “a miraculous double existence: the sacred power that the soul in heaven sends to the earthly body is transmitted through touching the body.” Thus, corporeal remains acted as conduits for a spiritual electricity that could flow further into the world once a physical connection had been made by the believer.

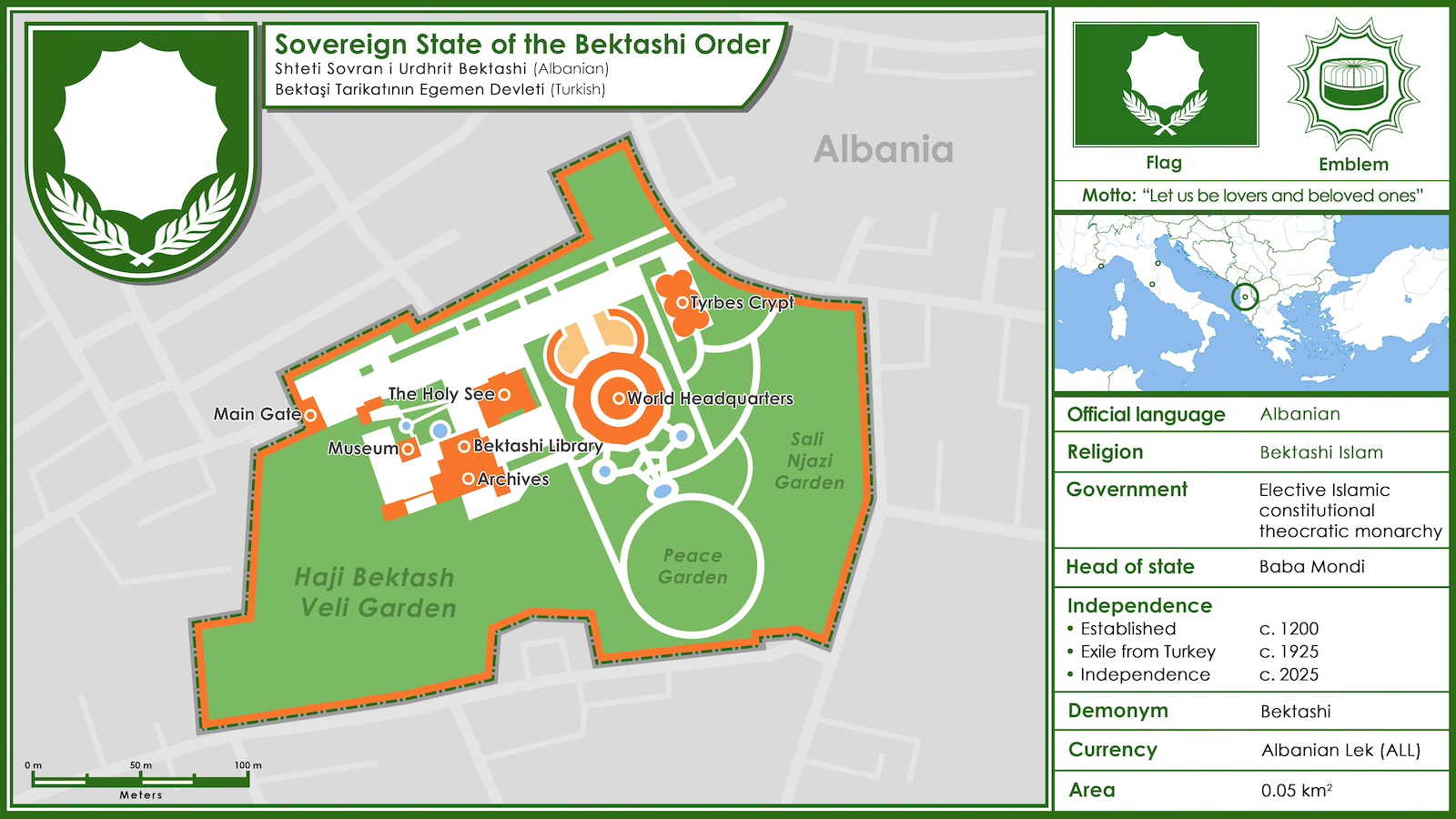

Relics and their housing, the reliquaries, performed a variety of roles in medieval life. Rulers collected and even traded relics and commissioned more and more elaborate reliquaries as tangible signs of their divine right to rule. Up until the fall of Constantinople in 1204, that city laid claim (thanks mostly to Constantine) to more relics than even Rome. Even the architecture of churches focused on relics. “Through relics and their cult,” writes Eric Palazzo, “the church was transformed into a true monumental reliquary whose ultimate purpose was to express a theological understanding of the liturgy.” Not only was the church centered on the relic, but sometimes the relic even participated in the liturgy. “The popularity of arm reliquaries [such as the one pictured above] from the twelfth century onward must be considered a result of their usefulness as liturgical props, which allowed clerics to animate a saint’s body during liturgical celebrations and processions,” Holger A. Klein explains. “In this way, the saint could literally bless, touch, and heal the faithful with his own hand.” Imagine Weekend at Bernie’s but with precious metals and jewels and inside a packed cathedral.

Objects such as the arm reliquary were known as “speaking reliquaries” because their shape said visually what it contained. But, as Cynthia Hahn asserts, “the form of the reliquary had more to do with its impact on the viewer than its presentation of information about its contents.” Calling them “charismatic” reliquaries, Hahn explores the non-“speaking” reliquary genre whose pure grandeur of craftsmanship and material combined to impress the glory of God and the power of the church beyond the spiritual charge of the object within. “Their production,” Hahn concludes, “as objects with the potential to have an arresting and decisive impact upon the senses and thereby to open a pathway of access to the soul, represents an act of remarkable creativity.” This almost God-like creativity, as Martina Bagnoli echoes, leads to a “comparison of the artist and God [that] elevated the value of the craftsman in intellectual circles by giving philosophical and rational dignity to the process through which artifacts were created.” Individuals could begin to put their names on their work as creative artists and not merely faceless artisans.

As a new day dawned, however, the darkness of the medieval period lifted and the world of the relic cult dissipated. Martin Luther rejected relics as part of the corrupt church infrastructure. Fake relics proliferated throughout Europe. If you reunited all the fragments of the True Cross, you could have built a personal armada. By one estimate, as many as 18 different locations claimed to own the Holy Prepuce, aka, Jesus’ foreskin forsaken at his circumcision (thus giving whole new meaning to the phrase “Keep the tip”). Through the Reformation and the Counter-Reformation, relics and reliquaries were either repurposed (if made of precious materials) or destroyed if they lacked non-sacred value. The Enlightenment flooded the last remnants of the relic with revelatory light. “A religious form that had been central in human history ended at once,” Angenendt eulogizes, “now appearing so absurd that it grew to epitomize the ‘dark’ Middle Ages.”

Alexander Nagel closes the catalog with his thought-provoking essay,“The Afterlife of the Reliquary.” After tracing the evolution of the relic cult to the more modern mania for souvenirs, Nagel sees Piero Manzoni’s Merda d’Artista (a 30-gram can of the conceptual artist’s excrement) as a modern take on the relic. “Manzoni’s provocations return us to a basic feature of the relic cult that had been lost during the early modern afterlife of the reliquary,” Nagel argues. “What makes the relic unique and valuable is its provenance: one keeps it and reveres it because it is the index or sample of a specific history, of an individual’s life. This is the basis of its efficacy, real or perceived.”

Nagel includes Joseph Cornell’s boxes as another modernization of the reliquary. I’d like to add Damien Hirst’s The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living, his infamous shark preserved in a vitrine, as another example of modern life’s continued use of the relic and reliquary. In essence, all 133 metalworks, sculptures, paintings, and illuminated manuscripts in the exhibition Treasures of Heaven: Saints, Relics and Devotion in Medieval Europe try to convey the idea of death in the mind of someone living, but death in the context of the eternal life in heaven, the source of the radiant power promised by the relic. Perhaps we can no longer be fervent members of the cult of the relic, but at the very least such shows and catalogs as Treasures of Heaven can help us understand the philosophy and theology of those who once studied and embraced a wholly different type of heavenly bodies.

[Image: Arm Reliquary of the Apostles. German (Lower Saxony), ca. 1190. Silver gilt over wood (oak), enamel (champlevé). 51 x 14 x 9.2 cm. The Cleveland Museum of Art, gift of the John Huntington Art and Polytechnic Trust, 1930.739.]

[Many thanks to the Walters Art Museum for the image above and to Yale University Press for providing me with a review copy of the catalog to the exhibition Treasures of Heaven: Saints, Relics and Devotion in Medieval Europe, which runs at the Walters Art Museum through May 15, 2011.]