Lee Krasner: Meet the Missus

When arrested in 1936 during a protest over the dismissal of 500 artists from the WPAFederal Art Project, Lee Krasner told the unsuspecting police officer processing her that her name was “Mary Cassatt.” (One of the similarly impish men arrested gave the name “Picasso.”) For most of her life and ever since her death in 1984, Krasner has been known primarily as Mrs. Jackson Pollock, wife and widow of the abstract expressionist who dominated American art during his brief life. Gail Levin’s Lee Krasner: A Biography corrects this case of mistaken identity in bringing Krasner out from behind the familiar labels and storylines to stand on her own as a powerfully fascinating figure and artist. Krasner’s “growing recognition” from the 2000 film Pollock (in which she was portrayed by Academy Award-winner Marcia Gay Harden) and novels such as John Updike‘s Seek My Face “owes more to fiction than fact,” Levin writes. Lee Krasner: A Biography proves that the facts are almost always more interesting.

Levin knew her subject intimately, having first met Krasner in 1971 when just a 22-year-old graduate student and the artist was a 62-year-old still seeking recognition on the cusp of the feminist ‘70s. Already author of works such as Becoming Judy Chicago (an honest appraisal of the often prickly feminist artist Judy Chicago) and Edward Hopper: An Intimate Biography (whose intimacy includes painter Josephine Nivison’s mistreatment at the hands of husband Edward Hopper), Levin continues to build with this biography perhaps the definitive story of women in American art in the twentieth century. If Nivison’s tale reflects the first third and Chicago’s the last, Krasner’s completes the trilogy of a century’s worth of discrimination and painfully slow recognition.

Of course, the temptation remains to skip ahead to the years Krasner spent with Pollock, beginning in 1936 when “Jack the Dripper” literally stumbled drunkenly into her life at an Artists Union dance and asked to cut in. To cut into Levin’s biography at the point would be to lose once more the compelling tale of the Brooklyn-born daughter of Russian immigrants who grew up reading Poe and Emerson before moving on to Nietzsche, Schopenhauer, and Rimbaud. Levin includes a sultry profile portrait of Krasner painted by Lee’s lover Igor Pantuhoff that perfectly captures the captivating personality and raw eroticism of the artist as a young woman. Pantuhoff, like Pollock would later, broke Krasner’s heart with a combination of dissolution and philandering, but she remained faithful to the end.

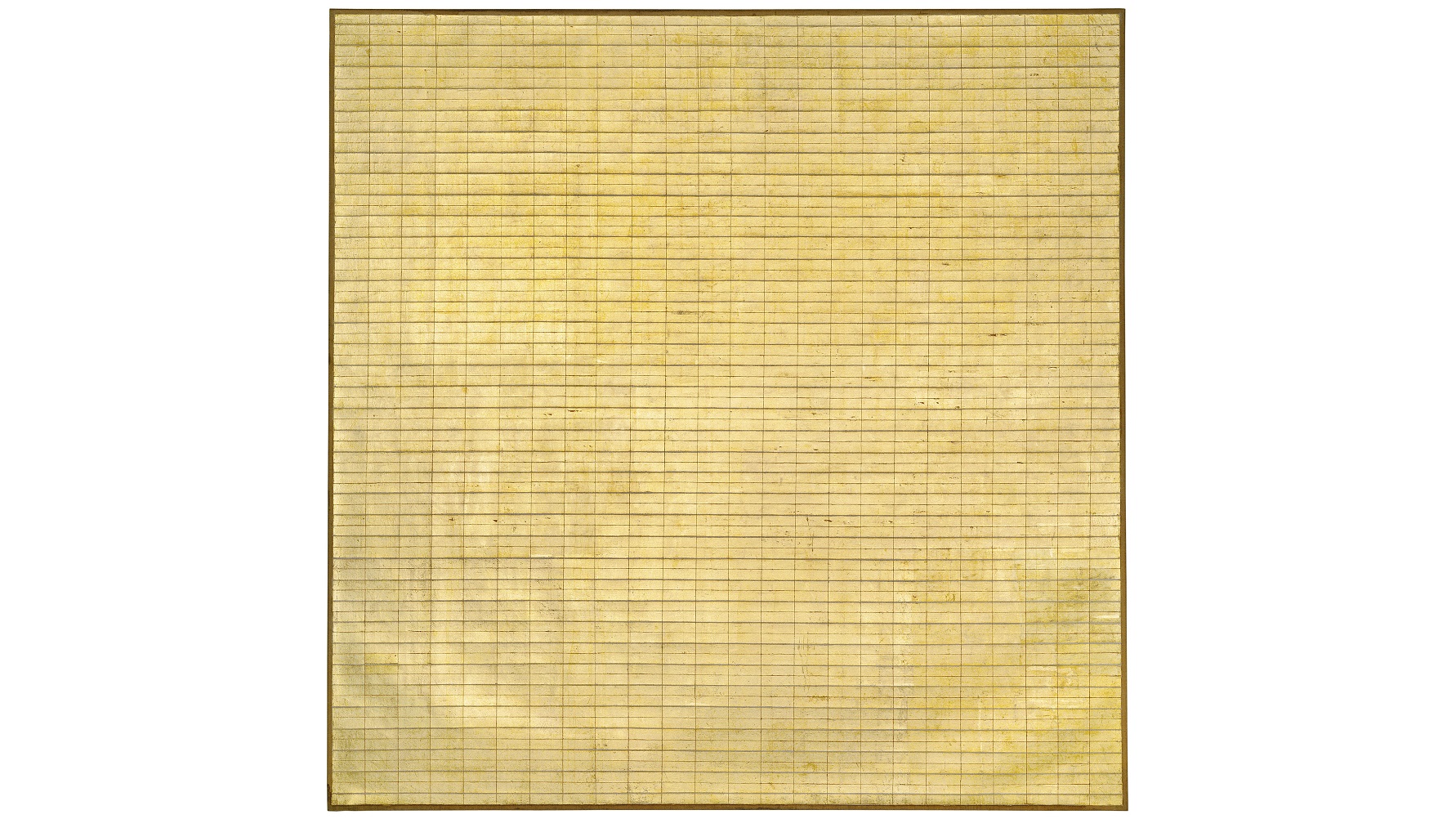

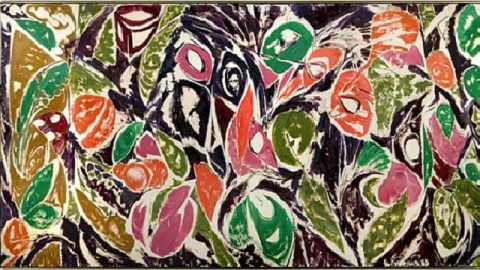

Levin includes a wide range of Krasner’s own art not just from the days with Pollock but from every phase of her career—the early Matisse-influenced works, later paintings informed by Mondrian (whom Krasner knew and even danced with in New York City jazz clubs), and work done under the tutelage of Hans Hofmann (one of the few male artists to support Krasner unconditionally). Even a work such as 1965’s Right Bird Left (shown above), in which a bird-like form rests on the left side of the image), takes on a different dimension when Levin makes the suggestion that Krasner may have been dyslexic, with the title alluding to Lee’s confusion of left and right.

Levin does her best to reverse the standard story of the birth of Abstract Expressionism. Critic Clement Greenberg usually gets credit as the father of the movement, but it was Krasner who introduced Greenberg to Pollock, Hofmann, Willem de Kooning, and others after Harold Rosenberg introduced Krasner to Greenberg at a party. “That guy wants to know about painting,” Rosenberg told Krasner of Greenberg, “talk to him about painting.” Krasner essentially schooled Greenberg on what would become the New York School of painting. In return, Krasner found herself relegated to a secondary role—the “missus” who painted a little—while the Abstract Expressionists movement became a boy’s club full of misogyny and sexist machismo. “Being dogmatically independent, I stepped on a lot of toes,” Levin quotes Krasner saying years later. “Human beings being what they are, one way to deal with that is denying me artistic recognition.” While Pollock lived, fellow artists such as de Kooning, Robert Motherwell, and Barnett Newman tolerated Lee as “the wife.” After Pollock’s death, however, the gloves came off.

The core of Levin’s biography and Krasner’s life, of course, remains the years with Pollock. Levin manages to balance out the joys and sorrows of the relationship. “It wasn’t Jackson who was stopping me,” Krasner confesses, “but the whole milieu in which we lived.” Speaking of their artistic relationship, Krasner says, “Painting is revelation, an act of love. There is no competitiveness in it.” Krasner later claimed that she and Pollock never had children because Pollock himself still was a child in too many needy ways. And, yet, the love and respect between them seems real, at least when Pollock’s alcoholism remained in check. Codependent years before the term existed, Krasner and Pollock formed a symbiosis that took a toll on both of them. “Though initially their needs had seemed compatible,” Levin explains, “as Pollock put [Krasner] under growing pressure, her health [colitis and painful digestive problems] began to break… As he turned increasingly to greater and greater amounts of alcohol, her life became more and more about trying to stop his drinking… His needs, which may have initially appealed to her wish to be maternal, had by now become suffocating.”

Pollock’s death in 1956 allowed Krasner to breathe once more, but also placed a greater burden on her as the widow entrusted with his legacy. Krasner championed Pollock’s art despite the rejection by many of his contemporaries of her own work and herself as a person. Levin navigates the waters of the post-Pollock years as deftly as Krasner herself did. As conditions changed slowly for the better, Krasner eventually found greater recognition, but always on her terms. Lee “recognized the need for a feminist movement,” Levin writes of Krasner in the feminist heyday of the 1970s, “but she had no affinity for feminist art, or anything with labels for that matter.” “I’m an artist—not a ‘woman artist’; not an ‘American artist,’” Krasner once said, independent as always.

Sometime in the late 1930s, Krasner wrote the following lines by Rimbaud on her studio wall: “What hearts shall I attack? What lie must I maintain? In what blood must I walk?” Considering her obvious affection for Krasner, Levin maintains an amazing level of objectivity throughout, especially in pointing out the inconsistencies—the lies maintained—in Krasner’s stories over the years, but leaves the question of forgetfulness or manipulation up to you. Levin reports, and you decide which hearts were attacked rightfully or wrongfully as Krasner stood by her man for three decades after his death. Krasner walked in the blood of Pollock painfully and proudly, knowing that she helped make him the man and artist he was. Gail Levin’s Lee Krasner: A Biography reminds us that Krasner’s path was never easy, but it was also never anything less than inspirational.

[Image:Lee Krasner. Right Bird Left, 1965.]