How the Supreme Court Can Avoid Ruling on Obamacare

Earlier this week I wrote that the Supreme Court was likely to take up a case challenging the Affordable Care Act in the next term. The Obama administration decided Monday not to ask the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals for an en banc review of its ruling that the provision requiring people to buy insurance—the so-called individual mandate—was unconstitutional. The administration’s decision strongly suggests that it will ask the Supreme Court to hear the case, since it doesn’t want the 11th Circuit’s decision to stand.

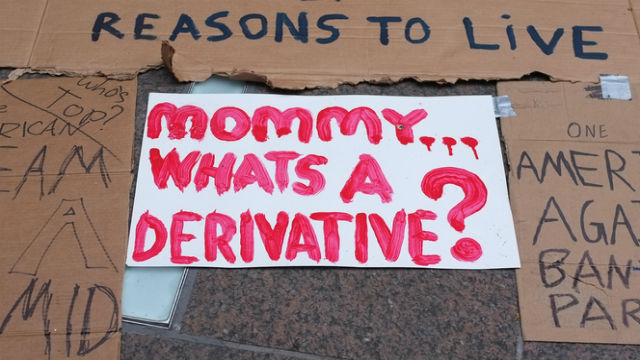

That puts the Supreme Court in the difficult position of having to rule on a politically charged piece of legislation during an election year. Rick Hasen suggests that a Supreme Court decision is win-win for Obama: either the court affirms the constitutionality of the law or it seems to overreach by overturning it. By the same token, ruling on the law may be a lose-lose proposition from the perspective of the court. Whatever the court decides it will seem to be taking sides in a political struggle. As Dahlia Lithwick says, there may not be five justices who want to want to make the court itself an election-year issue:

I don’t think Chief Justice John Roberts wants to borrow that kind of partisan trouble again so soon after Citizens United,the campaign-finance case that turned into an Obama talking point. And I am not certain that the short-term gain of striking down some or part of the ACA (embarrassing President Obama even to the point of affecting the election) is the kind of judicial end-game this court really cares about. Certainly there are one or two justices who might see striking down the ACA as a historic blow for freedom. But the long game at the court is measured in decades of slow doctrinal progress—as witnessed in the fight over handguns and the Second Amendment—and not in reviving the stalled federalism revolution just to score a point.

However much some members of the Roberts court might like to embarrass Obama, undermining the legitimacy of the court won’t help them establish a lasting legal precedent.

But while the Supreme Court can’t easily refuse to rule on a major piece of legislation when the lower court rulings conflict with another, I was wrong to suggest that the court necessarily had to rule on the constitutional question. As Lithwick says, they can put off taking up the 11th Circuit’s constitutionality argument by considering instead the technical question raised in the other circuit court cases about who has standing to challenge the individual mandate in the first place. As Lyle Denniston explains, those courts essentially found that the individual mandate can’t be challenged until it goes into effect and has an impact in 2014. As Sarah Kliff points out, neither the plaintiffs nor the Department of Justice may be interested in arguing the standing question. But putting off the constitutional question until then—when the court can consider the legal issues without the same political scrutiny—would probably suit the court just fine. Of course, since that would give the law more time to take effect, putting off the issue until then would probably suit Obama just fine too.

Photo: TheAgency