Erasing the Image of Osama Bin Laden

The cover of the May 16, 2011 issue of The New Yorker features a cartoon by Gürbüz Doğan Ekşioğlu in which the image of recently killed terrorist Osama Bin Laden is erased. Titled “Rubbed Out,” the painting depicts the freshly erased face of Bin Laden with the well-used pink rubber eraser laid carelessly on top (detail shown above). Now that it is almost definite that the photos of the dead Bin Laden will not be shown to the public any time soon, this may be the closest, and most poignant, thing. Ekşioğlu’s cartoon made me think back to Robert Rauschenberg’s famous 1953 work, Erased de Kooning Drawing, which lived up to its title in every way. Looking back on Rauschenberg’s thinking may hold some answers for what this new image may hold for the legacy of Bin Laden and the War on Terror.

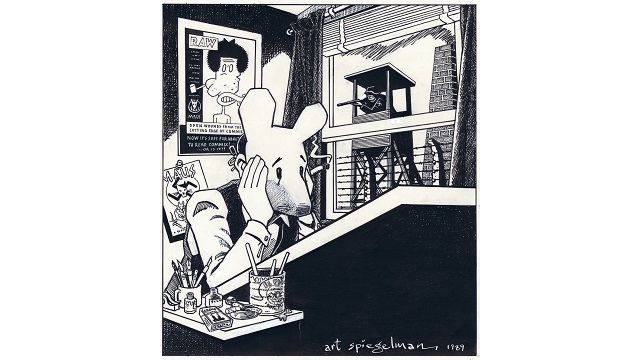

Ekşioğlu’s been one of the go-to artists for The New Yorker when attempting to put the emotions and ideas of The War on Terror and 9/11 into visual form specifically for a New York audience and in general for all Americans who read the magazine. For the September 15, 2003 cover, Ekşioğlu depicted the surviving New York City skyline all twinned in honor of the lost Twin Towers. Whereas Art Spiegelman’s unforgettable September 24, 2001 cover for The New Yorker captured perfectly the void the attacks left in the hearts of New Yorkers, Americans, and others around the world, Ekşioğlu’s covers have struck a lighter note in trying to fill that void with nostalgia for what once was. In this latest cover, it seems as if he wants to erase not only the face of Bin Laden, but also everything he did, as if we all could wake up tomorrow from some horrible nightmare and the towers and everything else would be back to normal.

“Rubbed Out” immediately brought to mind Rauschenberg’s infamous work of conceptual art from the early 1950s. Just a young artist himself trying to find his way, Rauschenberg wanted to strike back at the art establishment and find his niche in the pantheon. Armed with a fifth of Jack Daniels and that antiestablishment idea, Rauschenberg knocked on the door of the most famous American artist of the time, Willem de Kooning. Rauschenberg claimed later that he hoped de Kooning wouldn’t be home, but the Dutchman answered the door and invited him in. Over the bottle of Jack, the two artists discussed the idea of creating art by destroying art. Slightly skeptical and unhappy to have one of his works destroyed, de Kooning agreed to the project. Rauschenberg later recounted how de Kooning sifted through one portfolio only to close it, because he wanted to find something he’d truly miss. de Kooning looked through a second portfolio, this time seeking something not only that he’d miss, but also a work that would be difficult to erase. Rauschenberg claimed later that it took him a month to erase all traces of pencil, crayon, and charcoal from de Kooning’s drawing before titling it Erased de Kooning Drawing.

Like de Kooning’s drawing, Bin Laden took time to rub out—nearly a decade. But, like de Kooning, Bin Laden remained a giant in his field, almost a mythical figure at that. To move on, Rauschenberg needed to slay that giant—metaphorically, of course. For us to move on, we needed to get that monster under the bed who masterminded one unforgettably horrible day for everyone hoping for peace in the world. If you look closely at Rauschenberg’s handiwork, you can still see a ghostly remnant of de Kooning’s original, which serves as a reminder of what was lost, and what was gained. Even though we may never see the real-life photographs of Bin Laden dead, Ekşioğlu’s drawing perfectly conveys this ghostly afterlife of the terrorist—the legacy of what he did, what we lost, and, now, what we have gained. That faded face of terror should serve as a reminder that the monster under the bed was always just a man—a twisted man who advocated violent solutions to what he felt were the world’s problems. Turned into a cartoon, and a rubbed out cartoon at that, Bin Laden can finally be laid to rest.