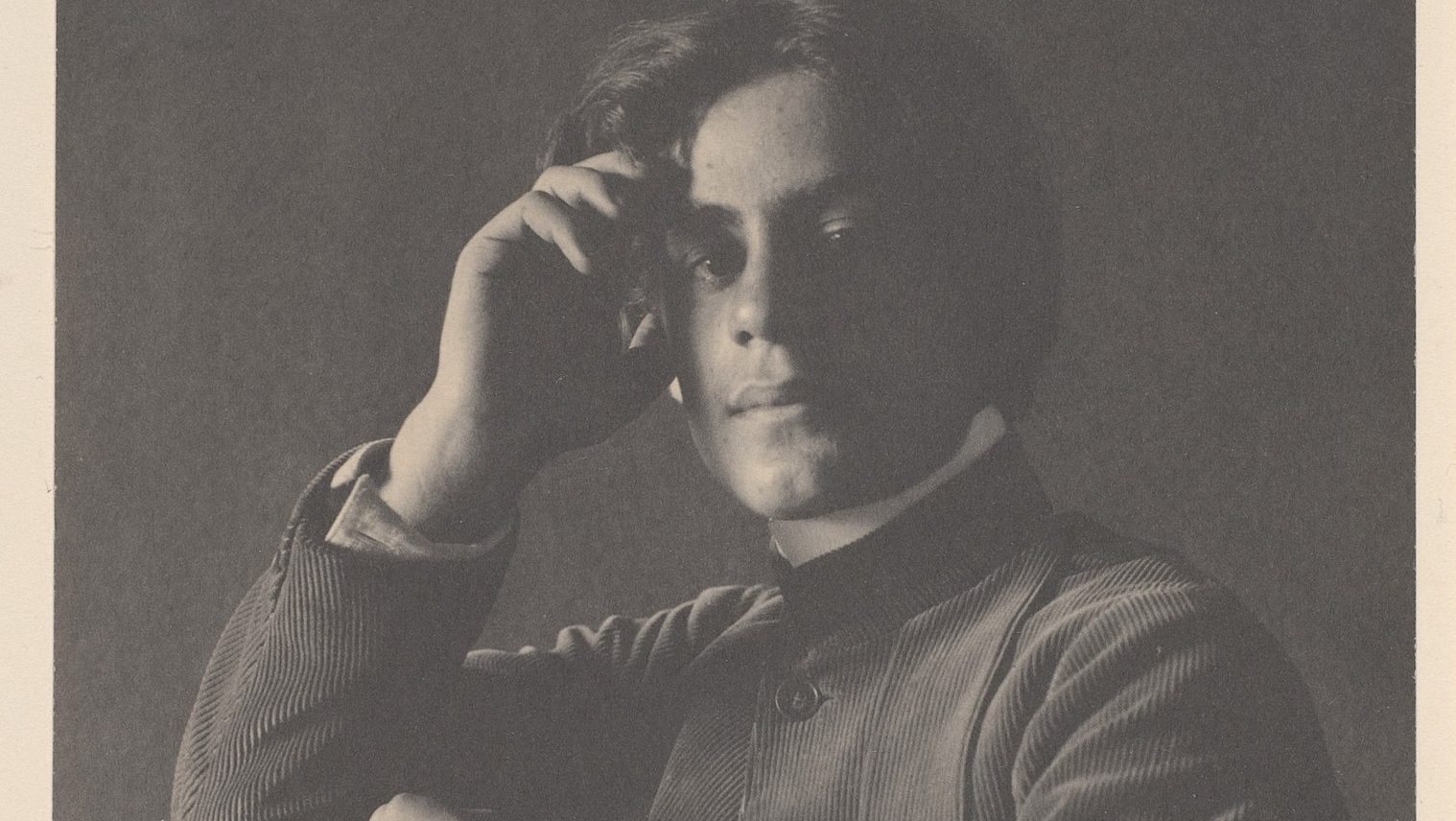

Eddie Long Trapped Between Religious Dogma And Legal Jeopardy

It’s kind of hard to live in Atlanta and not write a few words about Eddie Long, the pastor of the metro area’s own New Birth Missionary Baptist Church, who is under national scrutiny after being accused of having sexual relationships with some of his young male parishioners. Lawyers fill the airwaves on local morning talk shows, giving the kind of blow-by-blow legal analysis that Greta Van Sustern did during the O.J. trial. People you haven’t heard from in awhile call, wanting to know “what’s going on down there with that preacher?” And in break rooms, on Facebook and Twitter, a lot of folks are arguing over whether or not these allegations could be true, and if they are, whether or not the acts themselves constitute anything other than consensual sexual activity.

Looking past the salacious details, I wondered—could the nature of organized religion be partly responsible for a story that we seem to see here over and over again about religious leaders from all religious denominations?

Casting himself as the Bible’s ultimate underdog, Bishop Eddie Long went before thousands of faithful supporters at his megachurch last Sunday and promised to fight accusations that he lured four young men into sexual relationships.

“I feel like David against Goliath. But I got five rocks, and I haven’t thrown one yet,” Long said in his first public remarks since his accusers filed lawsuits last week claiming he abused his “spiritual authority.” He stopped short of denying the allegations but implied he was wronged by them.

Eddie Long, Georgia Megachurch Pastor, Vows To Fight Sex Scandal Allegations

The churches I see here in Atlanta these days probably aren’t that different from the ones I attended back in South Carolina as a child, except here, a lot of the pastors preach black prosperity. After a church gets a few hundred members, the pastor becomes a manager. After a church gets a couple thousand members, the pastor becomes an administrator. More than five thousand members and the minister is an executive, leading an enterprise with cashflows and payrolls more reminiscent of a mid-sized business.

However you may feel about him today, Eddie Long seems to have been a whirlwind force, a charismatic religious leader who turned a handful of followers into the largest black church in America. The excesses of his lifestyle that have been pictured on TV the last few days are being portrayed as if they are reminiscent of Roman emperors. Indeed, Mr. Long’s alleged behavior isn’t that much different than the activities of many Catholic priests who been found guilty of sexual misconduct.

Even thinking about leaving all that power and adulation behind has to be hard for Eddie Long. Which brings me back to something that I see as a fundamental problem organized religion has—an insistence on perpetuating the kinds of practices, rituals and customs originally designed to function as agents of social control.

Untethering personal spiritual salvation from the dogmatic rules meant to reinforce the status quo may be the future of religion, not edifice building, or ritualistic prostration before a human representative of an unearthly god.

Personal spiritual salvation, which is the foundation of most religions, is a pretty esoteric, mostly abstract condition that most people could probably achieve on their own if they were willing to work towards putting enough time and effort into it. Adding the physical component of church—the vestments, the buildings, the groupthink when it comes to interpreting the Bible—puts the heavy weight of building, supporting and maintaining an institution on top of a pastor’s commitment to spiritually guide his parishioners, the kind of weight and responsibility that may also breed a certain sense of entitlement for a job well done that a pastor’s more secular counterparts in the corporate world often believe is a standard part of their compensation packages.

Many people in the public, especially here in Atlanta, are frustrated this week by the megachurch pastor because he did not stand before his congregation last Sunday and emphatically proclaim “I am innocent. These young men are lying.” These dogmatists want a declaration from Long that is presented as simply and starkly as he presents his interpretation of the Gospels, a pronouncement that is as definitive as the “homosexuality is a sin” rhetoric this very same pastor has spouted from the pulpit and elsewhere.

But this self-proclaimed bishop is not just a man of God—he is also a very secular CEO of an multi-million dollar enterprise that employs hundreds and touches thousands of lives daily. An errant public utterance from CEO Long’s lips exposes the entire New Birth organization to the kind of legal jeopardy whose outcome could be calamitous to the church as an institution. Right now, Eddie Long is trapped between the religious dogma that he so enthusiastically teaches to his flock and the kind of legal jeopardy that can significantly impact the New Birth Missionary Baptist balance sheet.

So the public and his parishoners, like it or not, are going to get more sly allusions to David and Goliath in the weeks to come. They are going to hear rumors of settlement talks. They are going to see new pictures leaked to the media. Some members who feel that their pastor has not convinced them, through word or deed, that he didn’t engage in homosexual activity will begin to wander away.

As nice and neat and TV-like as it would be to watch Long confess his sins in front of a national audience, it just isn’t going to happen. There are many moving parts in a legal case. If the plaintiff’s lawyers mishandle a few procedures, or employ less than optimum deposition strategies, it is possible that Long could walk away from all of this. Whether he will be found guilty or innocent in a court of law I don’t know, but for anybody who is accused of wrongdoing to hand opposing counsel their case on a silver platter is ludicrous.

Walking away from the doubts about Eddie Long’s judgment that are floating around everywhere, from his congregation to the larger Atlanta community, will be a much harder case to make.