Dream Weaver: The Art of Brion Gysin

“Brion Gysin was a true subversive,” writes Laura Hoptman in Brion Gysin: Dream Machine, the text accompanying New York City’s New Museum’s exhibition of the same name. “Gay, stateless, polyglot, he had no family, no clique, no fixed profession, and, often, no fixed address. He claimed no religion, and no credo, save that we human beings were put on this earth with the ultimate goal of leaving it.” When Brion Gysin reached that ultimate goal in 1986, he left behind a tangled legacy—the natural consequence of the fluidity of his life and his creativity, both of which knew no borders. This first detailed study of Gysin’s life, art, and lasting influence, Brion Gysin: Dream Machine shows how he wove a life-long dream that many of today’s artists have merged with their own.

Born in England but raised in Canada, Gysin never felt comfortable in his own skin, feeling that his “oatmealy” exterior came from being “slipped into the wrong-colored package” at birth. Black culture and dark-skinned men both held an irresistible attraction. At 18, Gysin made his way to Paris, where he haunted the museums, studied the Renaissance, and ran in Surrealist circles, falling under the influence of Max Ernst. In 1935, on the eve of his inclusion in a Surrealist group show—his first public exhibition—Gyson watched Paul Eluard pull his works from the gallery walls on the order of Andre Breton, a rejection that reverberated throughout his life, despite soon being called the most promising painter of his generation. Gyson fled World War II in 1940 for the shores of America, where he met Paul and Jane Bowles. Brion followed Paul Bowles to Tangiers, where he fell in love with the culture and language, and even opened a restaurant called “1001 Nights.” Through Bowles, Gyson met William S. Burroughs, who would become Gyson’s artistic soul mate.

Already famous for the novel Junky, Burroughs found his creative equal in Gyson. When Gyson came up with the idea of the Cut-Up, a collage technique with words that led to Burroughs’ masterpiece, Naked Lunch, Burroughs, rather than Gyson, mistakenly became known as the creator of the Cut-Up technique. As James Grauerholz writes in his essay on the pair, “[T]he spotlight of reputation remained stubbornly fixed on Burroughs… a state of affairs that chafed Brion, and embarrassed William.” “[H]e moves into the painting and through it,” Burroughs said in admiration of Gyson, “his life and sanity at stake when he paints.” Burroughs saw the life-and-death intensity of Gyson’s art and refrained from painting himself until his friend’s death.

The catalogue shows the amazing range of Gyson’s art, from his Calligraphies, in which he combined the Japanese and Arabic script he loved into a mysterious web of meaning, to his Dreamachine, the stroboscopic spinning machine that projected light onto the closed eyelids of participants and induced dreamlike visions approximating those sparked by drugs, which Gyson knew extensively. (A do-it-yourself Dreamachine appears in the back of the catalogue for those who dare.) The most interesting and befuddling images are those taken from The Third Mind, Gyson’s verbal-visual project with Burroughs that marked the apex of their collaboration. Gyson’s art never fails to surprise and amaze, making you wonder why he’s never risen above cult status.

The cult of Gyson counts many members among contemporary artists. Keith Haring saw in Gyson an artistic forebear, both in terms of technique and sexuality. Haring admired Gyson’s “total control with no control at all,” the game of chance Brion played in his Cut-Ups, Calligraphies, and other work. A long list of working artists today express their debt to Gyson. Because of Gyson’s multimedia media critique, Hoptman explains, “it is easier to find connections in [Gyson’s] work to what is happening now in the artistic discourse than to the teleology of European/American postwar art.” Gyson simply had to wait for his time to arrive, the victim of being born too early for the ideas in his head.

As artist Jesse Bransford puts it, “Brion Gyson’s work resists consumption; it remains undigested.” Brion Gysin: Dream Machine gives us a lot to chew on. Gyson—the rejected Surrealist, the Beat who never joined the Beats—defies categorization. Like a dream, you just can’t grasp Gyson, but that’s the point of his art, who made a god of experimentation in defiance of a society that valued control. The dream Gyson weaves in his wake is one that remains attractive to anyone attracted to the freedom of ideas.

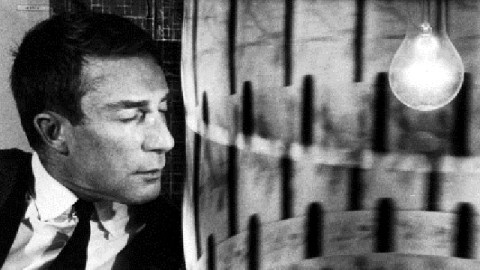

[Image: Brion Gysin with Dreamachine at Musée des Art Décoratifs, Paris, 1962. © Harold Chapman/Topham/The Image Works]

[Many thanks to Merrell Publishing for providing me with a review copy of Brion Gysin: Dream Machine, the catalogue to the New Museum exhibition that runs through October 3, 2010.]