Closing airspace over eruption due to Eyjafjallajökull ash was “right decision”

There has been an awful lot of debate about the decision to close the airspace over Europe for days during the beginning of the explosive phase at Eyjafjallajökull last spring. Many critics of the closure said that European officials didn’t have enough hard data, such as actual ash particulate counts or imagery of the location of ash in the atmosphere. However, much of this type of data was impossible to collect on a meaningful level because the apparatus was not in place for this type of rapid data collection of ash in the skies of Europe.

While it is easy to look back and say what should have happened, it can sometimes be useful as to help us better understand to how to handle the next crisis. It now appears that the EU officials made the right decision to err on the side of caution when it came to the volcanic ash over the continental and England/Ireland.

A new study by Gislason et al. (2011) in theProceedings of the National Academy of Sciences examined the ash from the eruption – collected during the airspace closure – and found some interesting features of the ash that made the airspace closure necessary:

An SEM image (similar to those posted by some Eruptions readers) of Eyjafjallajökull ash

Although EU officials did not know this information at the time of the closure, it does appear that their abundance of caution was likely prudent ~ of course, saying this now puts more deliberate thoughts into the heads of the EU officials during the crisis. However, these findings suggest that letting air traffic continue to move might have been a poor idea.

The study concludes by suggesting that in future eruptions, the size, shape and hardness of the ash be characterized quickly to help to assessment of potential hazard – both to aircraft and to inhalation. This would, of course, work in cooperation with any models to predict the location of the ash in the atmosphere, but would offer a much fuller picture of the threat. Most of the instrumentation (scanning electron microscopes, x-ray diffraction, etc.) to do these measurements of ash already exists at many universities and laboratories, so it shouldn’t be a challenge – however, as with any crisis, it falls to government to implement a plan that can be easily followed during an eruption. This way we will have all the appropriate information to make a more educated decision about the threat of ash in future eruptions.

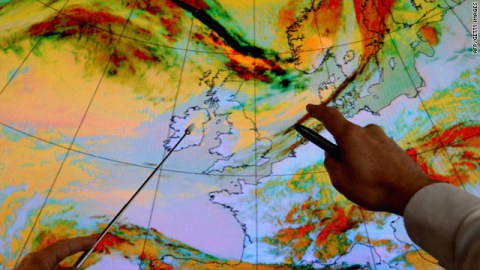

Top left: Examining the ash spreading over the North Atlantic and Europe during late April, 2011.